With all due respect to Agence France Presse, the left-right polarization in Costa Rica isn’t altogether unprecedented.

In 1948, Communist Party leader Manuel Mora was the head of the government army that faced José “Pepe” Figueres’ National Liberation Army. The alliance between Mora, Rafael Ángel Calderón Guardia’s populist Republican Party and Catholic Church Archbishop Victor Manuel Sanabria was an only-in-Costa Rica phenomena that produced the Social Security System and the country’s labor code, but also set up the Civil War with the onset of the Cold War.

One of the most telling questions directed to José María Villalta in the last debates was the one from a journalist who asked how he justified the alliance the Broad Front Party made with other parties from the political right in the Legislative Assembly. Villalta pointed to the Calderón-Mora-Sanabria pact as a precedent for his Broad Front Party alliances.

Despite the outcome of the 1948 Civil War, Costa Rica’s communist forebears have the respect of many in Costa Rica. Mora is a Benemérito de la Patria (National Hero), an honor bestowed by the Costa Rican Legislative Assembly, and another communist figure from that era, the writer Carmen Lyra, was also named Benemérita de la Patria and graces Costa Rica’s ₡20,000 note.

For several generations Costa Rica’s social peace has been based on the “handshake at Ochomogo,” where Figueres and Mora met to agree to the peaceful surrender of San José to end the Civil War, and where Figueres assured Mora that he planned to expand, not roll back, the social programs initiated by Calderón Guradia.

While the Communist Party was banned and its leaders forced into exile for a period, Mora eventually returned and led the party to victories for one or two congressmen per presidential term, who served as a third force that held the governing party to its social justice promises. That proved to be a remarkably stable formula which saw Costa Rica safely through the Cold War with no meaningful armed opposition.

Mora stuck to his orthodoxy in opposing armed conflict in Costa Rica following the Sandinista victory in Nicaragua, to the chagrin of some in the Communist Party, which split over the disagreement in tactics. The three-party formula began to come apart once the welfare state began being chipped away little by little, piece by piece, starting with the presidency of Luis Alberto Monge in the context of the Reagan revolution and the assault on big government in climes north and south.

But the rise of the Broad Front Party and also the strength of anti-free-trade Citizen Action Party candidate Luis Guillermo Solís is evidence that a great many Costa Ricans expect their government to play a large role in securing economic well-being. It just may be as Tico as gallo pinto.

And by the way, the ruling National Liberation Party is still a member of Socialist International.

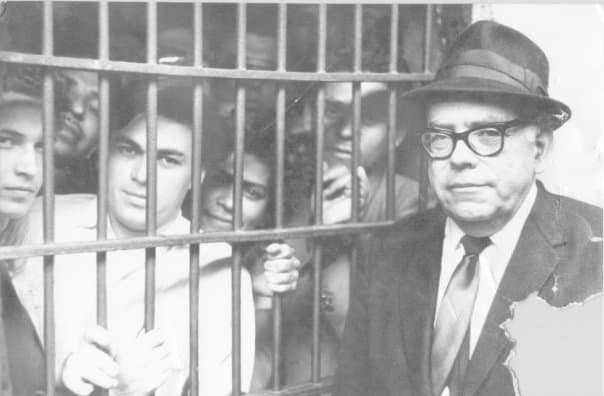

After the fall of the Iron Curtain, I interviewed Manuel Mora and asked him if he thought socialism was dead. He replied, “Are poverty and inequality dead? As long as there are poverty and inequality there will be socialism.”

José María Villalta may prove him right.

Formerly a reporter and assistant editor at The Tico Times, John McPhaul is a freelance writer who lives in San Juan, Puerto Rico.