The Costa Rican government’s struggle to launch fiscal reform to deal with its large and growing budget deficit brings into sharp focus the ongoing governance problems faced by President Luis Guillermo Solís and his administration.

With a Legislative Assembly in which Solís’ party lacks a majority, and faced with cutting deals to pass any fiscal reform legislation, Solís recently has been reaching out to opposition leaders in an effort to reach consensus on reducing the deficit, currently at more than 6.4 percent of gross domestic product.

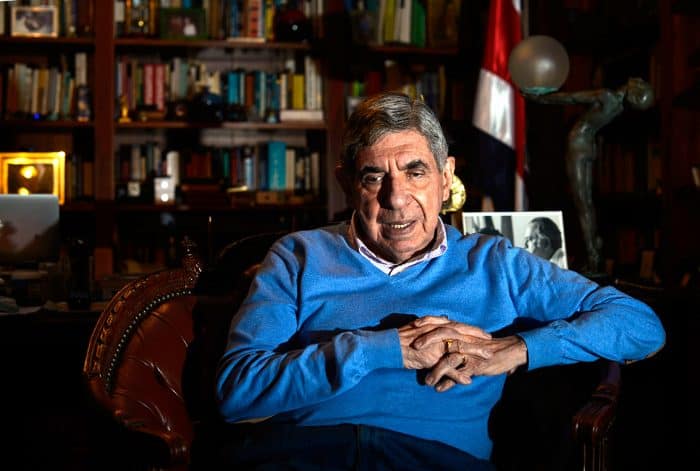

Last week, President Solís, who served in the government of two-time President Óscar Arias, paid a visit to the Rohrmoser home of the Nobel laureate in an effort to get Arias to use his influence with the opposition National Liberation Party (PLN) on the reform issue.

Saying that Costa Rica could not afford to let Solís fail, Arias offered to “roll up my sleeves and go to work.” But he was skeptical that Solís could succeed where three former presidential administrations – including Arias’ own – had failed, beginning with Abel Pacheco of the Social Christian Unity Party (PUSC) from 2002-2006.

Political scientist Constantino Urcuyo said Solís’ visit with Arias could have political importance given that Arias has clout with a wing of the PLN that is in his camp, and Arias also could sway other factions of Costa Rica’s oldest party.

But that support will come at a price, Urcuyo argued, which possibly includes the institution of a value-added tax, the privatization of electricity generation or cuts in government spending – all measures Arias has supported in the past.

Calls for cuts in government spending as a condition for raising taxes have been repeated by many in Costa Rica, including leaders of the country’s powerful chambers of commerce and industry.

But Solís has been equally adamant that fiscal reform should not be accomplished on the backs of Costa Rica’s poor and working classes.

On Wednesday, Solís submitted a fiscal reform bill to the Legislative Assembly that would increase revenue by $1.2 billion, about 2 percent of GDP. Among other things, it would replace the 13 percent sales tax with a value-added tax of the same rate to increase to 15 percent within two years. Low-income Costa Ricans – about 40 percent of the population – would receive refunds using an electronic system.

Solís also paid a visit to former President Abel Pacheco earlier this week in a courtesy call that observers dismissed as of little political importance, given that the elderly Pacheco has alienated most of the leaders of the PUSC party. In any case, PUSC already has fallen into disrepute with scandals that saw two of its former presidents arrested.

‘Dysfunctional democracy’

After his meeting with Solís, Arias lamented that Costa Rica has become ungovernable because leaders, he argued, have a difficult time implementing their policies.

“In this dysfunctional democracy that we have, it is difficult to achieve what you propose,” Arias said.

He also lamented the recent legislative alliance between Solís’ Citizen Action Party and the leftist Broad Front Party.

Arias said the country needs the confidence of investors – both internal and from abroad – in order to grow and continue to develop.

“An alliance with a communist party does not generate that confidence,” he said.

Arias added that he was glad Solís disavowed his party’s alliance with one that many believe have aligned themselves with other leftist parties in Latin America and that find inspiration in the policies and philosophy of the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez.

The Broad Front Party stunned Costa Rica’s political establishment by winning nine seats in the country’s Assembly in the 2014 elections, and some observers saw the PAC alliance with the leftist party as proof that the ruling party has a strong wing that harbors ideas in line with “chavismo.”

The 2014 elections also saw a party other than PLN or PUSC take power for the first time in recent history.

Though Solís and party founder Ottón Solís (no relation) were both formally members of the PLN, PAC came to power as an insurgent party made up of members from across the political spectrum, attracted by the party’s stand against the corruption that had created scandals for both major political parties in the recent past.

That anti-corruption stance aside, PAC has failed to become steady on its feet.

In an opinion piece in the daily La Nación, columnist and former Editor-in-Chief Eduardo Ulibarri said the administration is suffering from Solís’ inability to turn PAC into a true institutional party after he was elected president.

Ulbarri blamed in large part PAC founder Ottón Solís, who he said was intent on maintaining the party’s “ethical purity.”

“[Luis Guillermo Solís’ election] was the moment to make [PAC] into a modern political party with machinery, political philosophy, programmatic bases, stable leadership, opportunities for advancement and discipline. At the same time, it needed to develop its vocation for negotiation and governing,” Ulibarri wrote. “None of that happened, in large part because [Ottón] Solís presumed it would contradict the ethical purity to which he was obsessively tied.”

The result is a party that does not have the organization or coherence to govern as an established political party.

“Citizen Action, as a party, never came out of the closet,” Ulibarri continued. “Its internal weakness was a bill that came due when [Ottón] Solís was absent for 10 months, when a vacuum formed that made it possible for the party virtually to be taken over by one of its wings.”

As if the pressure from his own citizens is not enough, President Solís hosted a visit from Inter-American Development Bank President Luis Alberto Moreno on Tuesday, where Moreno told members of the press that the waiting for fiscal reform in the country ought to be over by now.