Despite Costa Rica’s talk of its commitment to promoting consumer-based renewable energy sources to produce electricity, the country is lagging in its efforts. One setback involves the country’s electricity distributors, who some say are dragging their feet on requirements to offer customers the option of connecting to the national grid with small-scale electricity generation projects from renewable sources.

These companies, which include cooperatives such as Electrificación Rural de Guanacaste (Coopeguanacaste) and Electrificación de Los Santos (Coopesantos), as well as the Empresa de Servicios Públicos de Heredia (ESPH) and the Compañía Nacional de Fuerza y Luz (CNFL), have until Oct. 8 – just nine days from now – to comply with a requirement to allow all residential and commercial customers in the country to generate their own electricity through solar, wind, biomass and other renewable sources.

However, some of these distributors interviewed by The Tico Times said complying with the requirement by the approaching deadline would be difficult. Asked to explain why, they pointed the finger at the Public Services Regulatory Authority (ARESEP) and the Environment Ministry (MINAE), which according to distributors, has lagged on meeting their responsibilities to assure that distributed generation becomes a reality countrywide.

But reality isn’t quite that simple.

ICE: A pioneer in distributed generation

Distributed generation from renewable sources began in Costa Rica as a pilot program carried out by the Costa Rican Electricity Institute, or ICE. In October 2010, ICE launched the “Distributed Generation Pilot Program for Personal Consumption” to test the demand from consumers to produce their own energy with small systems that are connected to the national electricity grid. Customers can produce their own electricity through the pilot program using solar, wind, biomass and hydropower.

The initial duration of the program was two years, but in October 2012, ICE extended it through 2015. As of October 2013, 177 customers had signed up for distributed generation across ICE’s broad service areas. According to ICE, the first customers were eager to invest in environmentally sustainable energy options. Today, some 300 customers are participating, and by year’s end the total generation capacity is expected to grow to approximately 7 MW. Over time, participating electricity customers have increasingly sought the savings distributed generation offers, especially given Costa Rica’s consistently escalating utility prices.

Following the launch of that pilot program, the government began promoting distributed generation as a cost-effective, sustainable option across the country. In April 2011, faced with resistance from distributors and ARESEP to implement net metering, MINAE published two rare decrees in the official government newspaper, La Gaceta, to require action on introducing distributed generation. The directives ordered electricity sector agencies to develop their own pilot programs and pressed ARESEP to create a regulatory framework.

(Read those decrees in Spanish here and here.)

That same year, ARESEP formed a commission composed of personnel from electricity distribution companies to define those regulations. According to Jim Ryan, president of ASI Power and Telemetry, a company that has long advocated for the introduction of net metering for all consumers, the customers who would potentially benefit from net metering – the “stakeholders” – were absent from the process.

By the end of 2013, the result of that work – a draft of the regulation titled “Planeación, Operación y Acceso al Sistema Eléctrico Nacional,” known by its acronym POASEN – was presented publicly in an open forum meant to generate discussion and feedback. According to Ryan, who participated in the public hearing, only a few private energy companies made public remarks at the hearing, and none of the distribution companies presented their positions.

(ARESEP called a public hearing for Nov. 27, 2013 to discuss the POASEN proposal. Read that document in Spanish here.)

According to the report “Pilot Program for Distributed Generation for Personal Consumption,” redacted by the coordinator of ICE’s pilot program, Alexandra Arias, ICE had included all of the country’s electricity distribution companies in its pilot program from the early stages. At first supportive, these companies later balked, saying they preferred to wait for the results of ICE’s program.

Finally, on April 8, 2014, ARESEP approved POASEN, publishing the directive into law in La Gaceta. The directive gave electricity distributors six months to develop and implement their own systems of distributed generation for consumers. That included the technical requirements for interconnection between consumers and the grid, a guarantee that the systems would function properly, a definition for the procedures to follow when applying as a consumer and installing a small-scale energy generation project, a pricing plan of how to measure and account for electricity produced by consumers, and a the technical elements of concessions and contracts – both between consumers and MINAE, and between distributors and consumers.

As Ryan noted, the regulation’s passage into law set Costa Rica on pace to catch up to other countries in the region with already established grid-interconnection rights and net metering, such as Panama, Guatemala and El Salvador, “not to mention many other countries in Europe, Asia, Australia and North America.”

(Read POASEN as published in La Gaceta in Spanish here.)

‘It’s complicated,’ say distributors

Implementing these steps has proven difficult, however. According to Marcelino Blanco, sub-director of electricity production at the Cooperativa de Electrificación Rural de San Carlos (Coopelesca), “The complicated issue here is that the tariff for [electricity] exchange on the grid has yet to be defined.”

That tariff must be set by ARESEP, Blanco said.

ARESEP spokeswoman Ana Carolina Mora told The Tico Times that in order to determine the tariff, the regulatory agency must first calculate the cost of interconnecting to the grid. An entire methodology needs to be designed, she said, and that likely won’t happen until the end of the year.

Asked if her company has all of the other requirements ready in case that tariff framework moves forward, Coopelesca’s Blanco said, “We’re working on all of it.”

“We’ve had the contract part of the process ready for some time, we were working on the technical requirements for interconnection, and we have a working group for the commercial side of it and the engineering side,” Blanco said. “We’ve been meeting frequently to comply with all of the requirements.”

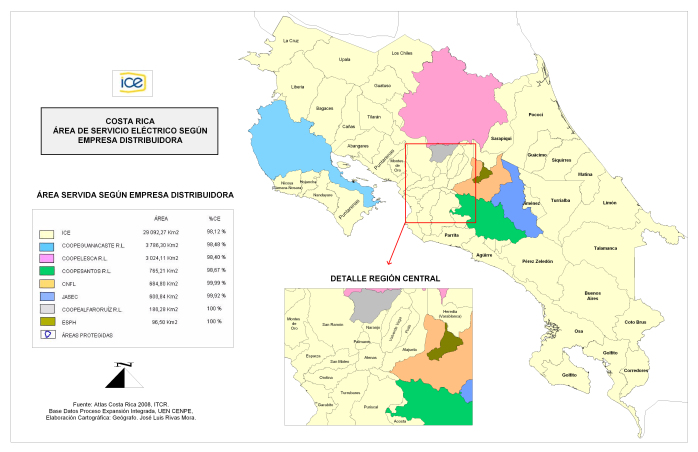

Coopelesca provides service to the cantons of San Carlos and parts of Sarapiquí, Grecia, San Ramón and Los Chiles.

The Tico Times asked if Coopelesca would meet the upcoming deadline.

“What’s happened is that we have been working on this, but we haven’t finished. Even if we do finish, it’s going to be difficult, due to the other requirements that aren’t ready, such as the concessions for generation that each customer must obtain. That’s definitely going to delay the issue,” Blanco said, referring to concessions that must be granted by MINAE to each customer hoping to connect to the grid and produce electricity.

Asked again if Coopelesca would meet the Oct. 8 deadline, Blanco said, “Yes, yes.”

MINAE’s role

A key part of the process is the consumer concession issued by MINAE. That concession allows the agency to have a registry of the locations and amount of production by customers. But in reality, in its current form, it is a mountain of paperwork, and concessions are currently designed for companies who plan to sell electricity to the grid. Small-scale consumer-generated electricity would not be sold, but rather exchanged for credits, requiring a different type of concession to be drafted.

Several electricity distributors accused MINAE of dragging its feet on the concession issue. But others said MINAE has been trying for years to reduce the bureaucracy involved in the concessions process, which is designed for larger projects by bigger companies, not small-scale consumer generation. Ryan said ARESEP – which has the authority to remove the concession obligation for small-scale distributed generation – is to blame for the delay, not MINAE.

The Tico Times attempted to clarify the issue with officials from MINAE but received no response.

“According to what they’ve told us, they’re evaluating a way to make the requirements more flexible in order to grant those authorizations [concessions],” ARESEP’s spokeswoman told The Tico Times.

In statements to the newspaper La República, Energy Vice Minister Irene Cañas said MINAE for several years has been trying to persuade ARESEP to eliminate the need for distributed generation concessions.

“MINAE could issue a decree on distributed generation concessions that would mean fewer requirements and a framework with which it’s easier to comply,” she said.

But in order to do that, Cañas said reforms would be needed for certain definitions contained in Costa Rica’s Electricity Law – such as public service, generator and distributor – that currently limit small-scale electricity production, adding another bureaucratic step that likely will delay the process even more as lawmakers become involved.

She added that the National Dialogue on Electric Energy, a panel created by President Luis Guillermo Solís to discuss national energy issues, could be the best forum for resolving these disputes. Lawmakers would have to approve any such agreement, likely “by the end of the year.”

ARESEP’s role

The Tico Times spoke with Marisol Arias, head of corporate communications at Coopeguanacaste, about POASEN and the likelihood its implementation would face delays. Arias said, “We’ve complied with the timetable,” but, “whether or not the regulation [POASEN] is implemented doesn’t depend on that, but rather on issues that are exclusively the responsibility of ARESEP and MINAE, [such as] the tariffs and the concessions.”

Coopeguanacaste services the northwestern province of Guanacaste in the districts of Liberia, Santa Cruz, Nicoya, Hojancha and Nandayure, as well as the province of Puntarenas in Lepanto, Jicaral and Paquera, among other areas. (Note: For a full list of areas covered by Coopeguanacaste, see below at end of story.)

According to Arias, the company has finished its “technical requirements” and sent them to ARESEP, along with a proposal for distributed generation service contracts. A framework for receiving requests from consumers also will be finished by the end of this month, she said.

“As soon as ARESEP approves what we’ve submitted to date, Coopeguanacaste will finish the integral procedure that summarizes all of the steps to respond to [customer] requests [for distributed generation], from the receipt of a request from a consumer to the connection of that consumer’s generator,” Arias said.

Melvin Pacheco, sub-director of operations at the Consorcio Nacional de Empresas de Electrificación de Costa Rica (Coneléctricas), also took a jab at ARESEP.

“The timetable will be met in October. What’s funny to us is that ARESEP issues a statement saying that the [electricity distribution] companies are failing to comply, but we haven’t even reached the deadline,” Pacheco said.

On Sept. 2, ARESEP issued a statement reminding distributors that they must submit a timetable for the implementation of the various steps in the process. ARESEP said all of the companies had complied except Coope Alfaro Ruíz. ARESEP also stated that the companies were required to submit a draft of the contracts.

“Due to the failure [by companies] to meet the deadline for these contract drafts, this week ARESEP asks for those contracts,” the ARESEP statement said.

But according to Pacheco, ARESEP is the entity that has failed to meet deadlines. He echoed other companies’ statements on tariffs, and he added that the regulatory agency has not yet defined the technical regulations that govern where in the point of interconnection distributors’ infrastructure stops and where a consumer’s system begins.

“On this point in particular, there needs to be definitions on issues of operational safety, because, for example, if the distributor provides maintenance and shuts off electricity service, the generators should be able to automatically disconnect in order not to send energy to the grid, because that could cause problems of human safety,” Pacheco said.

“For October, given these urgent issues that ARESEP has been unable to resolve, I think that distributors will be in a legal vacuum, and won’t be able to say, ‘We’re ready to establish distributed generation in our areas,’” Pacheco said.

Controversy over net metering and surplus electricity

One of the conditions needed to ensure that distributed generation systems are economically viable and efficient in terms of investment and operation is the ability to recognize the flow of energy from the consumer to the grid, ICE noted in an explanation of its pilot program. A billing system must be in place that subtracts the amount of electricity a consumer produces from the amount the consumer uses.

Currently, ICE’s pilot program does not purchase surplus electricity produced by customers. Instead, consumers accumulate kilowatt-hour credits for later use, while ICE enjoys the use of free injected power into their network. But POASEN offers an option to change that structure – a contentious issue for distributors.

POASEN creates two types of net metering. One is a common method used by ICE and other countries that already have net-metering rules. Under this “simple” type of net metering, electricity customers with solar power, for example, use a distributor’s grid as a type of virtual battery, exporting energy generated during the day and using it when needed at a later period.

The grid can immediately use this free surplus electricity in exchange for kilowatt credits. Customers exchange those credits during periods when their consumption exceeds solar production, typically during nighttime hours, for example.

According to Ryan, one of the benefits to distributors is that solar and wind – the two most commonly used types of distributed generation – both produce their highest levels during the times of the day and year when distributors and generators are under the most stress, such as during summertime days – and especially late summer, when hydropower resources are depleted and oil-fired generation is increased.

But Marcelino Blanco said Coopelesca doesn’t believe it should have to pay a one-to-one rate for electricity surplus because distributors have fixed costs. A credit system, Blanco argued, would transfer those fixed costs to all electricity customers, regardless of whether they produced their own energy. Blanco said Coopelesca hopes to propose their own methodology to determine tariffs.

Critics say these types of proposals by the distributors could make investment in distributed generation less attractive.

Meanwhile, ICE’s pilot program refutes Coopelesca’s argument by showing that generation for personal consumption actually optimizes total investment when surplus electricity is used by the grid.

ICE’s summary report on its pilot program notes that, “There is a mutual benefit between electricity companies and customers when eventually there is energy flow into the grid.” These same benefits are well documented in mature solar markets such as in the U.S. states of California and New England.

Pacheco argued that lower-income electricity consumers would be discriminated against with a distributed generation system at the proposed surplus tariffs.

“Not everyone can afford to invest $10,000 or $11,000 in solar panels, for example, to recover that investment and reduce their electric bills,” he said.

Pacheco claimed that a solar system only would benefit people whose electricity bills average between ¢60,000 ($111) and ¢70,000 ($129) per month. The average residential electricity bill in Costa Rica, he claimed, is only ¢15,000 ($28) to ¢20,000 ($37).

“Only a financially select group of Costa Ricans could invest in this,” Pacheco claimed.

Pacheco also said distributed generation would reduce sales for distributors while their costs would remain fixed, a common argument used by companies against the distributed generation framework POASEN seeks to create.

“They’d have the same crews, they’d have to tend to the same power outages, and those costs would be passed on by ARESEP through rate hikes to people who aren’t in a position to invest in distributed generation,” he said.

The other side of the battle

Ryan, whose company installs solar and wind technology for consumers in Costa Rica, is highly critical of the arguments set forth by the distributors.

“I sort of chuckle because it sounds like they’re opposed to net metering because it doesn’t benefit all parties. Yet they are not necessarily a champion of the modest household that is under stress for their electric bill. So it’s interesting to hear them use this defense,” Ryan told The Tico Times.

“We have historic low levels of equipment prices, historic high tariff prices, and we need to make solar available to any family with good credit, regardless of their wealth,” Ryan said.

He claimed that, “Utilities always inflate the costs and minimize the benefits for those who are thinking about going solar. That is their front-line propaganda to dissuade clients from ever making the investment.”

He added that “for a modest home, for a family with an electricity bill of ¢10,000 [$18] a month, that’s the equivalent of about 700 kilowatts per annum, which is very small. You are looking at 60 kilowatt-hours per month.

“Here in Guanacaste we can produce that much with just a couple of solar panels, maybe [costing] a couple of thousand dollars. This is an example of the utility companies grossly misstating the economics,” he said.

Ryan acknowledged the need for low-income families to be able to access financing for renewable technologies. He said he is working with a nonprofit Costa Rican organization and private donors to develop a revolving financing program for low- to medium-income families who “spend a much higher percentage of family income on electricity and are in the greatest need of price relief” from high utility costs.

“This is a real issue, and for years we’ve talked with banks and lending institutions to try to get a recognition that this is a good business. Slowly that is changing and banks are starting to offer financing,” he said.

ICE’s report notes that some banks in Costa Rica already offer financing options for small-scale, renewable energy generation projects. Some nonprofit organizations also have funding for these types of projects, ICE said.

Ryan scoffed at the argument that offering net metering with one-for-one kWh credits hurts distributors’ bottom lines. That claim, he said, “entirely ignores the significant economic benefits [distributors] receive from distributed generation networks,” a point that ICE also makes in its report.

“The solar peak production during midday – and especially during summer months – is also when the utilities are buying the most expensive power or are short of power, and a lot of oil is being consumed in generating peaking power. It’s a perfect complement to hydro-resources, which are nearly exhausted in the mid- to late-summer months, and right now especially, with the pattern of rain we have here in Guanacaste,” Ryan said. “Until the last couple of weeks, we’ve been 90 percent below normal rainfall in Guanacaste. That is catastrophic if the majority of your generation is run-of-river flow or is reservoir-based.”

Ryan had a different take on the impact that net metering would have on distributors: “Both their fixed costs and their operating costs do go down, and they go down significantly. Permanent expenses should decline due to lower maintenance and especially lower investment requirements to upgrade or add transmission and distribution lines. And what about the free energy they are receiving every day, and especially at their peak ‘network-stress’ times, like daytimes during summer months?”

For Ryan, the foot-dragging that continues over distributed generation and small-scale renewable energy production is a combination of intentional resistance and bureaucratic mire.

“This is a battle,” he said. “The distributors don’t want this, and they will say and do what is necessary in trying to prevent it.”

•

Rules for participating in the consumer electricity distributed generation program

Consumers who would like to install a small-scale electricity generation project for personal consumption from renewable sources – such as solar, wind or biomass – and who want to interconnect with the national electricity grid must comply with the following rules outlined by POASEN. The date for this program to be up and running is Oct. 8. However, it appears increasingly unlikely that the agencies and companies involved will be ready by that date. Consumers must:

- Pay ICE or the relevant electricity distributor for connection request studies.

- Pay the costs associated with interconnection and network services for transport and distribution, according to a tariff set by ARESEP.

- Design, build, mount, enable and provide maintenance to consumer-end equipment according to norms set by ICE or the relevant distributor.

- Install, operate and maintain the necessary equipment for protection, interruption, measurement, telecommunications, failure notification, supervision and control.

- Pay for the energy consumed at the point of connection according to a tariff set by ARESEP.

- Sign a connection contract with ICE or the relevant distributor to connect to the national electricity grid.

(Source: “Planeación, operación y acceso al sistema eléctrico nacional,” AR-NT-POASEN, La Gaceta, April 8, 2014.)

To contact the reporter of this story, email: fpomareda@ticotimes.net. To contact the editor, email: dboddiger@ticotimes.net.

•

*As requested by the distributor Electrificación Rural de Guanacaste (Coopeguanacaste), we are including here a full list of the company’s coverage area, which spans some 3,700 square kilomters. In Guanacaste, the canton of Liberia in two districts: Liberia and Nacascolo (Guardia); in Carrillo in Filadelfia and Belén and partially in Palmira y Sardinal; in Santa Cruz, nine complete districts, including Santa Cruz, Cartagena, Tempate, Cabo Velas, Veintisiete de Abril, Diriá, Bolsón, Cuajiniquil and Tamarindo; in Nicoya, San Antonio, Quebrada Honda and parts of Nicoya, Mansión, Nosara and Sámara; part of the canton of Hojancha and the canton of Nandayure; in the province of Puntarenas, Lepanto, Jicaral and Paquera.