SÃO PAULO, Brazil — Antonio da Silva sat atop a dilapidated wooden throne in the middle of the city. Below him a man shined his brown leather shoes, and in front, the bustling public square Praça da Se came to life. Street performers and sidewalk evangelists harmonized and sermonized away the final hours before chaos was scheduled to give way to competition.

“Tomorrow is Brazil,” da Silva, a 58-year retiree wearing a Brazil soccer cap, said Wednesday.

The first of 64 World Cup matches is scheduled to take place on Thursday afternoon, as Croatia takes on powerful Brazil, which is trying to become the first country since France in 1998 to hoist the championship trophy on its home turf. Evidence of the tournament is easy to find all across the country, where buildings are decorated green and yellow, the national colors, and inflatable soccer balls are as common as Neymar jerseys, celebrating the Brazilian wunderkind with boy-band good looks and sneaky-fast feet.

But signs of resistance are also difficult to miss, and enthusiasm has been capricious at best. Spray-painted on a building along Rua Augusta is the popular grassroots slogan, protester chant and social media hashtag: “There won’t be a Cup.” A graffiti artist was more to the point along Rua Major Nataneal, etching stark black letters on a brick wall: “[Forget] FIFA,” the expletive aimed at the sport’s governing body.

Recommended: Brazilian street artist creates World Cup’s first viral image

For months, government and sporting officials have wondered whether this conflicted, soccer-loving nation would fully get on-board with the World Cup. As competition gets underway Thursday, the more apt question seems to be: Can it continue to resist?

“There was a strong resistance a few weeks ago, but it’s much less than what it was,” said Lucas Rodrigues, 23, standing outside a cafe near Paulista Avenue, site of several passionate anti-World Cup protests. “Getting closer to the event, people are participating much more in the event.”

The days, weeks and months leading up to the opening match have been largely overshadowed by social unrest and infrastructure failings of the host nation. Police have tear-gassed citizens and workers have died building new stadiums.

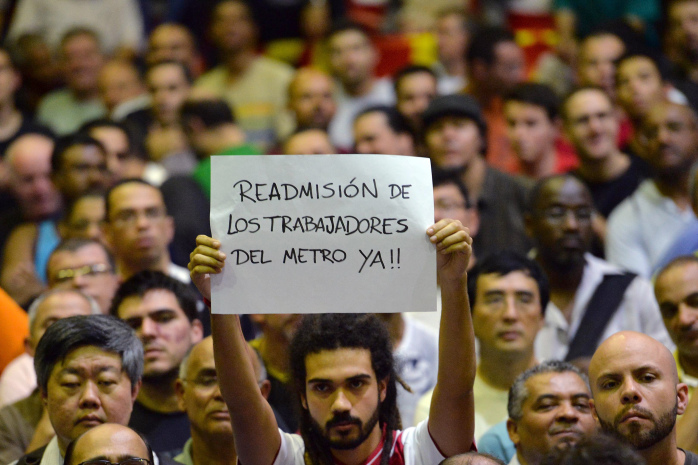

The costly preparations gave a platform for demonstrators and provided opportunity for a variety of labor strikes: bus drivers, police officers, garbage workers and transit employees. Thousands of Brazilians have protested working conditions and the government money being poured into staging the tournament — an estimated price tag ranging from $11 billion to $14 billion, according to news reports. Many feel the money would have been better spent on education, health care and infrastructure.

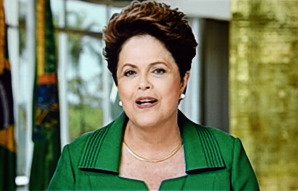

President Dilma Rousseff took to nationwide television this week, pleading with her country to support the tournament, dismissing the alarms sounded by “pessimists” and “defeatists.”

“I’m certain that, in the 12 host cities, visitors are going to mix with a happy, generous and hospitable people, and be impressed by a nation full of natural beauty and which fights each day to become more equal,” she said.

Brazil is a colorful nation made up of eclectic people from all sorts of backgrounds. It’s not easy to find a single common cause, though surveys have found that more than half of Brazilians — perhaps as many as two out of every three residents — oppose the tournament taking place here.

“That’s our discontentment,” said Hugo Nogueira, a 39-year-old shopworker, sopped in tattoo ink. “But football is our passion.”

Nogueira is among many Brazilians who will continue to passively protest the event by avoiding the high-priced tickets to matches. Of course, he says, he’ll still watch on television.

“This Cup was made for foreigners,” Nogueira said. “It wasn’t made for Brazilians.”

Thirty-two countries are competing for the title of global soccer king. The tournament opens with 15 days of round-robin group play. The top two teams from each of the eight groups advance to the single-elimination round of 16, which sets the stage for the quarterfinals, semifinals and finally the championship match, scheduled for July 13 in Rio de Janeiro.

Players have largely been isolated from any day-to-day chaos on Brazilian streets. U.S. players mostly observe it from a bus window, traveling back and forth from a grand hotel to a posh practice facility, which features an ATM in one corner of the field and peacocks roaming the grounds.

“We haven’t seen much,” U.S. midfielder Fabian Johnson said of São Paulo. “It’s pretty crowded, a lot of traffic.”

Teams have spent months trying to plan for Brazil’s wide-ranging elements. While many cities will see sweat-inducing temperatures topping 90 degrees, games in Fortaleza on the northern coast could be played in the low 60s F or high 50s. Rain is a constant threat across the country, too, and the city of Manaus, located in the middle of the Amazon rain forest, promises to be humid.

“It’s gonna be a World Cup of patience, of knowing how to deal with the elements, of being able to suffer at times,” said U.S. midfielder Michael Bradley. “I think we’re excited by it. When you talk about playing in the heat, the travel, it doesn’t bother us.”

Thursday has been designated a national holiday and most Brazilians are taking the day off work. While the anti-Cup movement continues to be active and vocal, in recent days and weeks, flags, bunting and decorations have begun to decorate Brazilian streets — led by shops, bars and restaurants. In Rio de Janeiro, tourists and vendors alike have sprouted up on cue.

“It is all last minute, because we were deciding whether to support Brazil,” said Rubens da Silva, 55, who was hanging up bunting outside the Good Bar in central Rio in a grey drizzle. “But we are all Brazilians. We will support Brazil.”

In some cases, a little commercial assistance was required. Rio’s Santa Marta favela accepted free paint from a paint company to decorate its narrow streets and houses last weekend in pro-Cup colors.

“People weren’t excited. It was getting closer. But a week ago, they decided to start painting,” said Salete Martins, 44, a Santa Marta resident. “In truth, Brazilians never give up, ever.

“Football is number one. It is last minute. But we support Brazil.”

© 2014, The Washington Post

Follow all of our World Cup coverage at the hashtag #Brazil 2014