A pair of researchers from Canada and England discovered the third-smallest winged insect ever known, but there is still much to learn about this denizen of the forest floors of Costa Rica.

The Tinkerbella nana – only three times as long as a human hair is wide – was named one of the top 10 new species of 2014 by the International Institute for Species Exploration. London-based researcher John Noyes found the wasp after tediously searching through the forest floor debris in various parts of Costa Rica, including Heredia, Alajuela, Guanacaste and Puntarenas. After hours of extracting the speck-sized bugs from the debris, Noyes, shipped his specimens to his Canadian colleague, John Huber.

First discovered in April 2013, and yet to be observed while alive, the life of the tinker bell wasp remains an enigma. Due to its minute size, this wasp’s world would feel very alien to us. As insects shrink, their legs and wings must find a way to overcome physical forces, which humans may never think twice about, such as surface tension, viscosity and inertia. For the smallest of bugs, the air itself thickens.

“They don’t fly like birds, but probably swim through the air like a fish,” Noyes said.

Huber went even further, saying the air might feel like moving through molasses. Tinker bell, 0.25 mm in length, brought up the question of what minimum size is even possible for an insect. As limbs and wings shrink, eventually no room will remain for muscles capable of movement. A related wasp also in the fairy fly family, the Kikiki – found in Costa Rica, Trinidad and Hawaii – is currently the world’s smallest flying insect, at 0.15 mm.

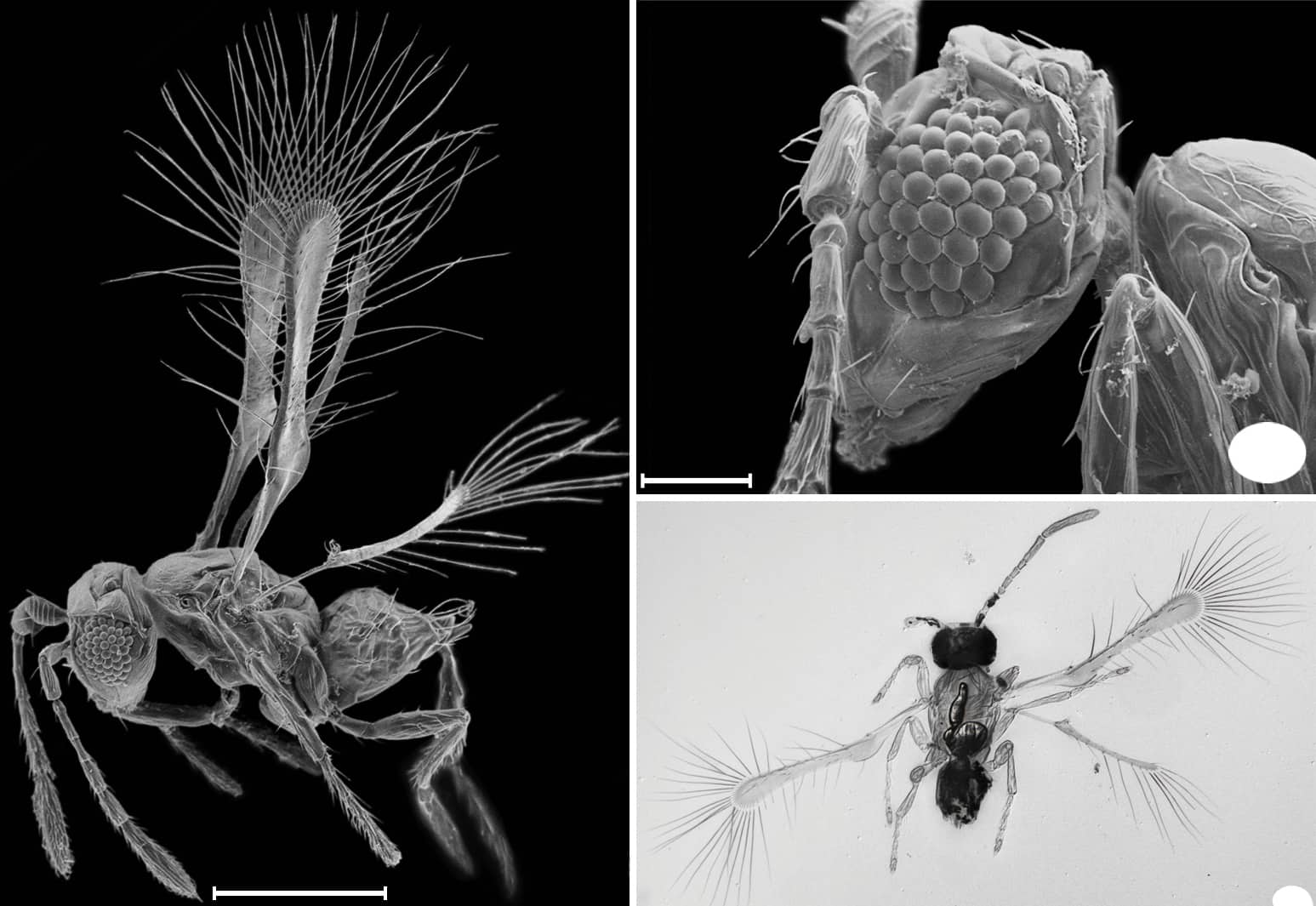

Aside from its size, tinker bell’s most striking feature is its hairy wings, the common feature of fairy flies. Due to its small size, the wasp needs to do everything it can to save energy. Huber had originally thought the fringes helped deal with turbulence, but he since believes they help artificially lengthen the wing, without the bug having to grow a larger, heavier wing membrane.

Having only dead tinker bells, the researchers could only draw comparisons to other wasps. In another family of wasps with similar fringed wings they have observed an impressive 350 wing beats per second, according to Huber.

“We really need to film these things in flight,” Huber said.

Like many tropical wasps, tinker bell has a dark side. The parasitic wasp likely begins its life eating its way out of the egg of another insect. Noyes said that adult mothers probably home in on the eggs of another insect that lives in the leaf litter and detritus of the jungle floor. Their victims are likely another tiny insect that feeds off fungus in decaying plant matter. Tinker bell hatches from its own egg, consumes its host’s egg while a larva, and eventually pupating and bursting from its host in its adult form.

Discovering the microscopic wasp was no small feat. Noyes is a veteran researcher in Costa Rica, first visiting in 1991. Noyes said he drags a net through the forest floor and bushes in places like La Selva Biological station in Sarapiquí and around remote parts near the Rincón de la Vieja Volcano in Guanacaste. The piles of dirt and rotting plant matter are soaked in alcohol and then travel to the laboratory, where Noyes sorts through them one three-milliliter teaspoon at a time.

“It’s all very laborious,” Noyes said. “It just depends on how hard you want the specimens to start with.”

Using forceps, Noyes separates the insects from debris under a microscope, going through each teaspoon multiple times.

“You think of a meter cubed in the forest and there’s probably a lot going on in there,” Noyes said.

This is especially true in biologically rich Costa Rica. Noyes said that there are about 2,000 species of known wasps just in Costa Rica, which is one and a half times as many as exist in all of Europe and Northern Asia.

For Huber, the discovery of Tinkerbella as well as his previous discovery of Kikiki, reveal a vast and unknown world that still demands exploration.

“We know very little and it’s only now that we’re developing the technology to find them and it’s generating new species and new genera of insects,” Huber said.

Unfortunately, the clock is working against Huber and Noyes, as climate change and deforestation threaten the discovery of more micro-insects.

“They’re going extinct before we even know it,” Huber said.