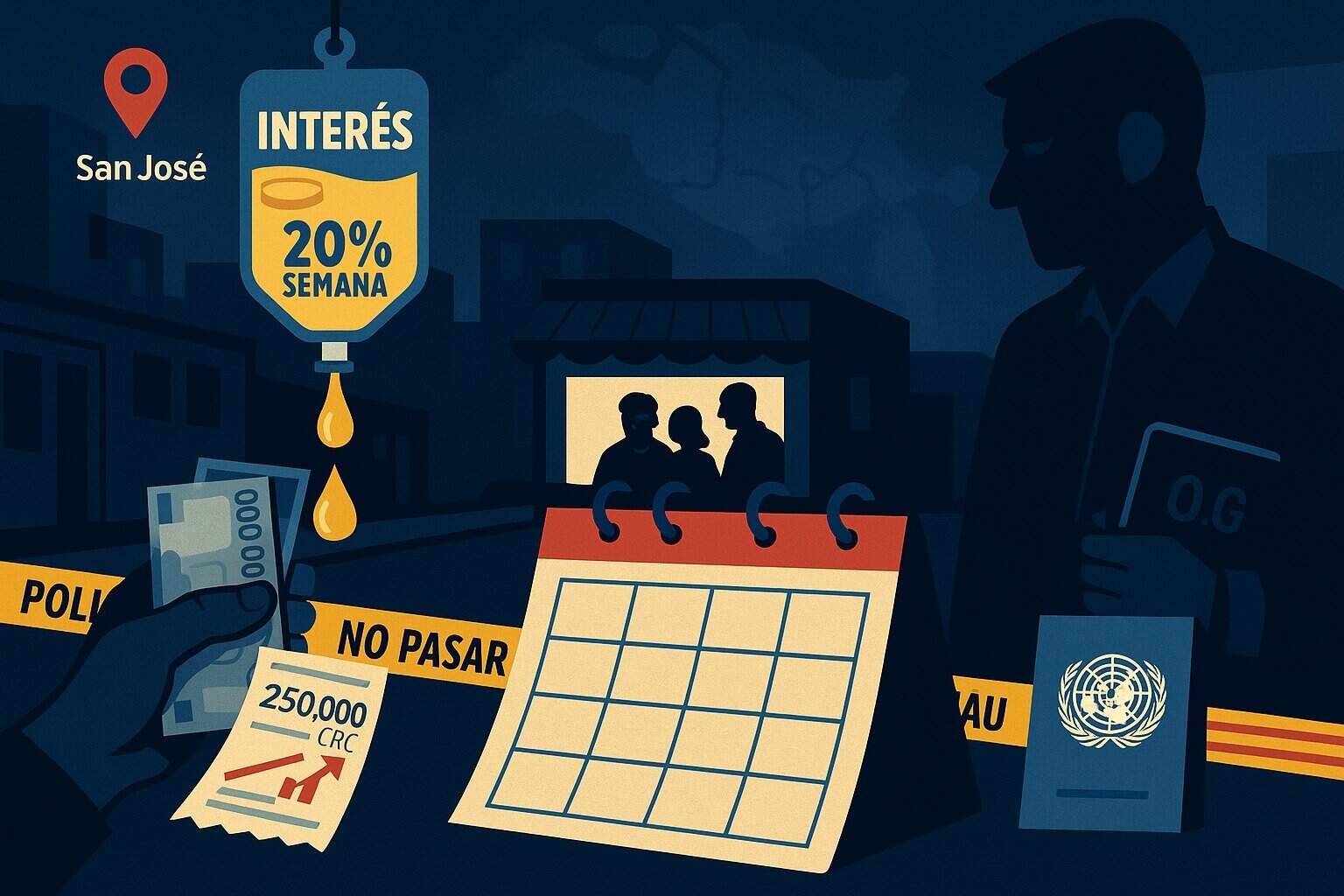

A new United Nations study sheds light on the rapid spread of informal lending schemes called “gota a gota” across Costa Rica, where high-interest loans often lead to extortion and violence. These operations, once limited to certain communities, now affect a wider range of people facing financial pressures.

The report, released this week by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, details how these networks function and their effects on daily life. Researchers point out that borrowers come from varied backgrounds, not just those in poverty or informal jobs. People turn to these loans for quick cash to cover health costs, accidents, or basic needs.

Data shows the average loan falls between 200,000 and 350,000 colones, with interest rates hitting over 20 percent per week or month. That far exceeds the legal cap of about 38 percent per year. A 2023 financial literacy survey found that 5.3 percent of Costa Ricans have used these services, with the highest rates among those aged 35 to 44 who didn’t finish high school.

These lending groups run in a scattered way, with several providers sharing the same areas. They rely on clear roles: those who supply the money, others who distribute it, support teams for logistics, and collectors who might serve multiple groups. Most networks stay small, around eight people, but some handle larger sums and show more organization.

When payments falter, the response turns harsh. Lenders might offer more money to refinance, adding extra interest, or sell the debt to other groups. If that fails, they shift to pressure tactics like threats, stealing items, or direct harm. Between 2023 and 2024, authorities logged 2,018 extortion cases tied to these loans. Over half occurred in San José, but every province reported incidents. Complaints rise from May through October, peaking in that final month.

This pattern points to deeper issues. As one expert in the study noted, these loans reflect gaps in access to fair credit and economic strains that push people into risky choices. Without steps to offer better options, the networks could grow stronger, refine their methods, and increase harm.

Costa Rica has seen a steady climb in related crimes. In 2023 alone, police handled 816 extortion reports linked to gota a gota. By August 2024, another 579 cases emerged, showing no slowdown. Lawmakers recently made these practices a specific offense, aiming to give prosecutors stronger tools.

Links to broader crime add urgency. Older cases tie these lenders to drug groups, using loans to launder funds or control areas. In Costa Rica’s shifting economy, where jobs remain unstable for many, these schemes fill a void left by formal banks that demand paperwork or collateral.

The study calls for a mix of fixes: expand low-cost credit through community programs, boost education on finances, and tighten enforcement. Police raids have disrupted some operations, but the decentralized setup makes full takedowns hard.

For those caught in the cycle, the personal toll runs high. Borrowers face constant stress from collectors who show up daily or weekly, demanding payments drop by drop – hence the name. Missed deadlines bring immediate fallout, from verbal warnings to worse.

As Costa Rica continues to deal with rising insecurity, this report serves as a call to action. Officials and community leaders must address the root causes, like limited banking access, to curb the spread. Left unchecked, gota a gota could deepen divides and fuel more conflict in neighborhoods.