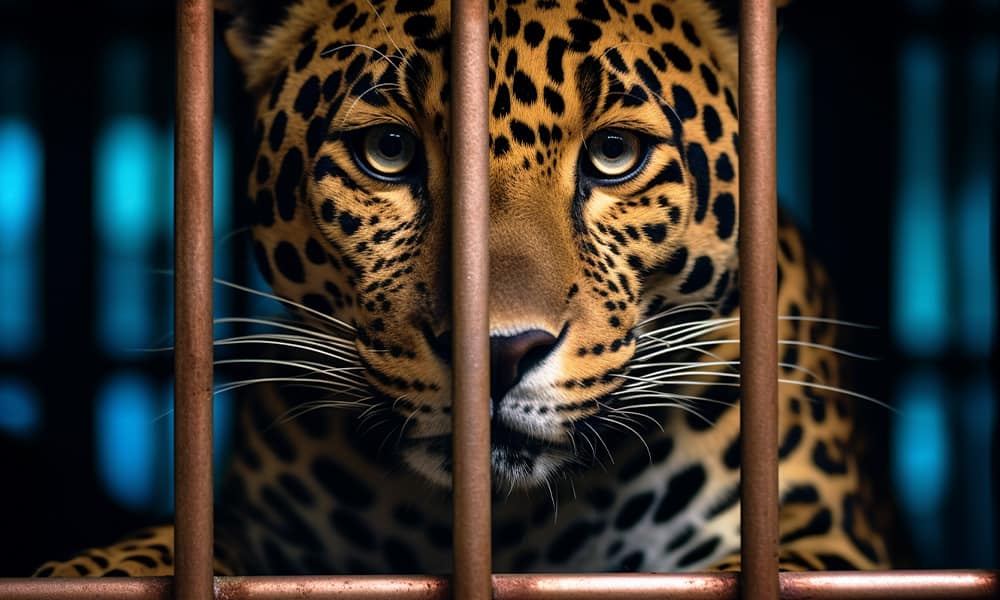

A caged jaguar couple on a ranch uncovered a cruel fashion among Ecuador’s drug traffickers. In the style of cocaine baron Pablo Escobar, the capos run clandestine zoos that endanger the wildlife in this megadiverse country.

It is not the only case, but it is one of the most striking. In May, police found the enormous endangered felines perched on a log and surrounded by bars.

The animals were on a property belonging to Wilder Sánchez Farfán, alias “Cat” Farfán, an Ecuadorian drug lord linked to the Mexican Jalisco New Generation cartel and wanted by US authorities after his arrest in Colombia in February.

In addition to the jaguars, police found Amazonian parrots, pheasants, parakeets and other exotic birds allegedly smuggled in from China and Korea.

The phenomenon is “recent” and coincides with the increase in violence and drug trafficking in Ecuador, the new logistics center for the export of cocaine to the United States and Europe, Major Darwin Robles, head of the police’s Environmental Protection Unit (UPMA) said.

“For about four years now, in about 20 or 25 anti-drug operations,” wild animals began to appear, he details.

The figures for seizure of trafficked animals and rescue of species are on the rise in the megadiverse nation, one of the most biodiverse on the planet. In 2022, the police confiscated and cared for 6,817 specimens compared to 5,951 in 2021.

Like other confiscated animals, the jaguars and birds of “Cat” Farfán were taken to specialized wildlife centers to receive veterinary care, with a view to assessing possible reintegration.

However, in most cases returning to a natural environment is impossible.

Status

When Escobar was gunned down by police in 1993, his flamingos, giraffes, zebras and kangaroos were moved to zoos. But a herd of hippos was left to fend for itself and now reproduces unchecked in the face of environmental authorities’ helplessness.

There are now more than a hundred huge beasts that attack people and are a headache for Colombia. Ecuadorian drug traffickers to “possibly demonstrate their power, their purchasing power, their economic capacity, have this kind of places in the pure style of Colombian drug traffickers from the 70s or 80s,” points out Robles.

In smaller operations related to drug trafficking, officers have found turtles, snakes, skins and animal heads as trophies.

“Having an animal is a status symbol (…) That shows within organized crime the rank within this network,” an anonymous spokesman for the US NGO WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society) said, which collaborates with national authorities.

And he gives an example: “I got myself a small tiger, but if I can get a jaguar it’s much more.” In that competition, exotic animals are one more element that adds to the properties, luxury cars, works of art, jewelry.

In Ecuador, wildlife trafficking is punished with up to three years in prison, while in countries like Colombia and Peru sentences go up to nine and 20 years, respectively.

Fear of humans

In the Tueri wildlife hospital in Quito, small tigers, monkeys, porcupines, parrots and owls victimized by species trafficking are recovering. The birds are fed with tweezers, their injuries treated and the possibility of reintroduction to their natural environment evaluated.

But of all the patients, only 20% will be able to return to their habitat. The rest will have to live in shelters as they no longer know how to survive in wild contexts and others will die from the severity of their injuries.

The WCS spokesman laments that animal collectors do not understand the impact of removing an animal from nature. “Unfortunately, to have a little monkey at home you caused the hunter to kill the family and violently extract the baby,” he says.

Shelters like Jardín Alado Ilaló, which works with the police, are the final destination for surviving trafficked animals. There are parrots without beaks, with amputated claws or unable to find food on their own will spend the rest of their days. A few will have the opportunity, after weeks and even months of rehabilitation, to fly again.

Fear of humans is a lifeline in a possible reintroduction.

“If we make contact and see that the animal is not scared of us, we can no longer reinsert it. If we realize that as a chick it is scared, afraid, there is a possibility,” says Cecilia Guaña, in charge of caring for birds of prey and psittacids, such as macaws, at Jardín Alado Ilaló.