For love, Andry Hernández left his native Venezuela to cross the dangerous Darién jungle between Colombia and Panama in an attempt to reunite with Paul Díaz in the United States. His dream ended locked inside a maximum-security prison in El Salvador.

After four months imprisoned in the Terrorism Confinement Center (Cecot), where he had been sent by U.S. authorities, he was released along with 251 fellow detainees and has now returned to his country.

Surrounded by his family, Andry, a makeup artist and hairdresser, is trying to overcome the trauma of the hell he endured in Cecot, where he entered on March 15.

At that time, he was trying to reunite with Paul, a 49-year-old Puerto Rican-American psychologist. The two had met online two years earlier, and though they had never seen each other in person, they had planned to meet in Philadelphia to become a couple. They even dreamed of starting an organization to help children with HIV and cancer.

Andry hoped for a better life, to escape homophobia in Venezuela, a very conservative country where same-sex marriage does not exist. He also dreamed of working in Hollywood or in beauty pageants. He insists he has not given up on those dreams, or on a life with Paul, though he is no longer certain of his future.

For now, he is thinking about opening a beauty salon in his hometown of Capacho (Táchira, western Venezuela) to earn a living doing what he loves most: makeup.

In 2024, like 300,000 other Venezuelans, he set out to cross the Darién jungle, a passage that has cost many migrants their lives. In his pocket, he carried two identical bracelets—one for Paul and one for himself. He crossed Central America, even the U.S. border, but was detained and expelled to Mexico.

He then requested an appointment with U.S. authorities through the CBP One app, which allowed undocumented migrants—especially Venezuelans—to apply for asylum in the United States. He was assigned a date: August 29, 2024.

“I did it,” he remembers thinking when he crossed the border again and saw the U.S. flag. But it was a disappointment.

He sacrificed himself for love

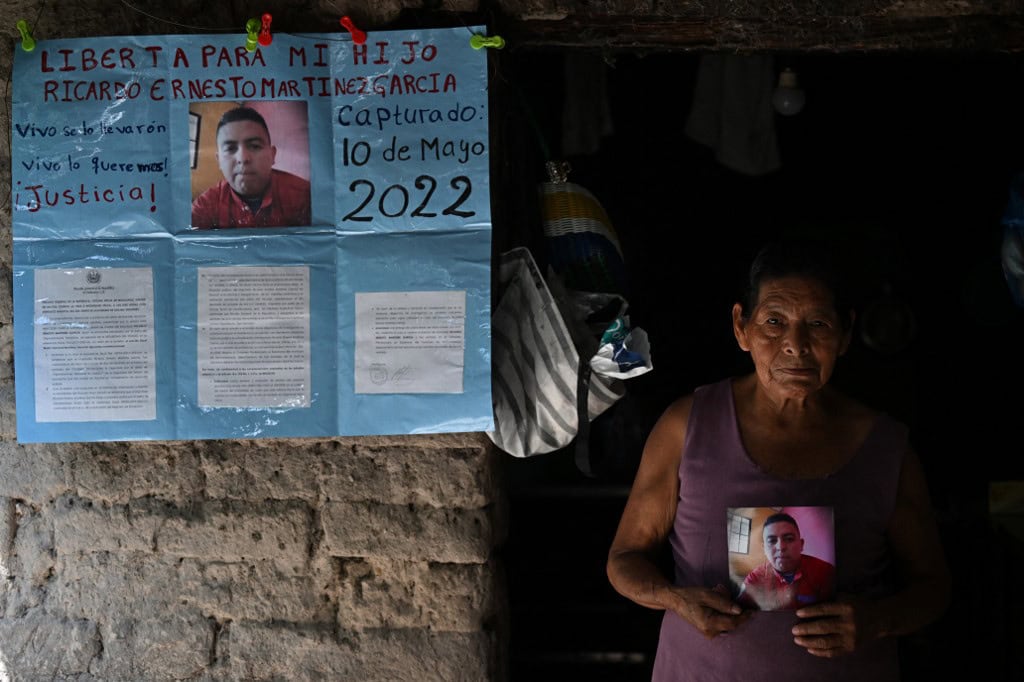

Andry’s face made headlines from the moment the news broke of his transfer to Cecot until his release and return to Venezuela on July 18, following a prisoner exchange agreement between the United States and Venezuela.

Two crown tattoos on his wrists led security services to label him dangerous and likely a member of the notorious Tren de Aragua gang.

Although he explained he had never been convicted or accused of a crime and that the tattoos represented the Three Wise Men—a tradition that every January brings thousands of people together in Capacho—he was not believed.

He was sent to a detention center in Otay Mesa, California, along with about a hundred people, most of them Venezuelans with tattoos. “That day I thought about my parents, about Paul, about everything I had risked only to get nothing,” he says.

Paul hired a lawyer to try to free Andry, stressing that he had no criminal record. “It’s completely ridiculous. I feel very guilty about this situation… For love, he sacrificed himself. He told me: ‘I want to be with you, I want a quiet life, I want to work.’”

The worst was yet to come. Compared with Cecot—the prison built by President Nayib Bukele—Otay Mesa was “a luxury hotel,” though not free of homophobic episodes or even a case of harassment.

He was one of the 252 Venezuelans that the Trump administration expelled to Cecot, relying on the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. What followed were four months of beatings, insults, and sexual abuse in Cecot.

“I’m gay, I’m a hairdresser, please don’t cut my hair, I’m not a criminal!” he recalls begging the guards in vain, kneeling on the floor of the prison inaugurated by Bukele in 2023. That was only the beginning of a long ordeal of abuse in that “piece of hell.”

Endless hours of abuse

Andry turned 32 while imprisoned in Cecot. One day, overcome by the heat and a terrible headache, he bent down to splash some water on himself. “What are you doing bathing in secret? That’s not allowed—we have to punish you,” a guard shouted. He was taken to a 9-square-meter isolation cell, without light or ventilation, nicknamed “the island.”

“They told me: ‘Get on your knees!’” Andry recalls. “I felt four people surrounding me, touching me; one forced me to perform oral sex, another rubbed my genitals with a baton, pushed it between my legs and shoved it upward.”

With no sense of time, he believes the abuse lasted about two “endless” hours. His release was a relief. He was welcomed as a hero in Capacho. He savors the regained freedom, but the chances of building a life with Paul have diminished.

“You have to keep your feet on the ground, you have to face reality: he is there, I am here,” he says, before breaking down in tears. Andry does not rule out trying to return to the United States. “If they let me in, yes, I’ll go,” he says, though for now the plan is to reunite with Paul in Colombia in a few months.

“Are you thinking of coming to see me?” Paul asks. “Do you still need to ask?” Andry replies with a wide smile.