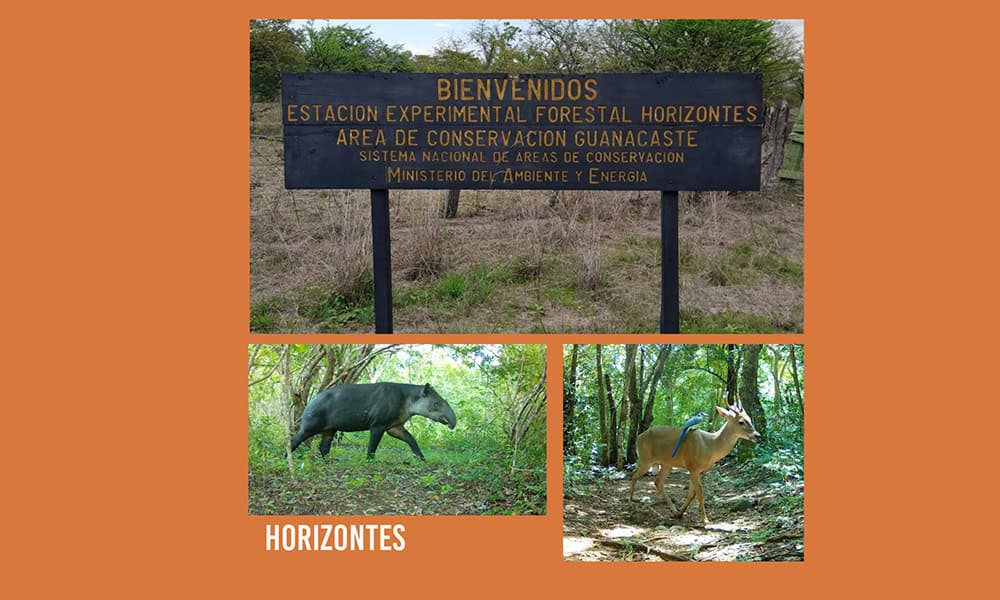

I got to know Horizontes, more specifically Estación Experimental Forestal Horizontes, by accident. I had a contract to place camera traps on a few private farms in Guanacaste. Two of those farms happened to only be accessible by riding a rented horse named Superman on a six hour round trip directly through the tropical dry forest that makes up this protected area. As Superman and I slowly rode under the canopy of the forest, I thought to myself, ‘I love it here. I need to get some camera traps in this forest.’

After some starts and stops, plenty of paperwork, and with the help of the administrators who are in charge of everything that happens there, I was able to team up with the staff of Horizontes and start a wildlife monitoring program using camera traps. The unique aspect of this particular project is that you, Tico Times reader, are invited to participate.

The project is set up as a wildlife tour where the general public is invited into the forest with me to review camera traps. While I’m not above shameless self-promotion (Definitely do the tour!), that’s not the point of this article. Horizontes and its history are worth learning about even without taking into account the fun and innovative camera trap project that you should absolutely participate in.

As I mentioned before, Horizontes consists of tropical dry forest. This is a type of habitat that features long seasons of hot, dry weather, followed by seasons of significant rain. The differences between the look and feel of the forest in dry season and rainy season are incredible. During rainy season, you’d be excused for thinking you’re in the jungle. Everything is lush, green, and wet. During the height of dry season, the trees are mostly leafless, the dry heat is oppressive, and the verdant greens have been replaced with dusty browns.

One might imagine that it may be difficult for a large number of creatures to live in such a dynamic environment. How many species can deal with such dramatic climatic changes? In the case of Horizontes, the answer is a whole lot. Within its boundaries, Horizontes hosts three species of monkey, at least four species of feline, countless birds, and an array of species of trees and plants that have evolved to survive in this harsh environment.

Personally, I’ve seen a crocodile with a deer in its mouth, a tapir chilling in a lake, a jaguarundi sipping from a pool of water, and a rattlesnake gliding across the road in front of me. I feel like I have a chance to see something wonderful every time I drive through the front gate.

What makes this spectacular amount of biodiversity even more remarkable is the history of Horizontes, which was once a cattle farm. A few days ago I had the opportunity to participate in a meeting where a famous conservationist that has spent the better part of his life preserving and exploring large sections of northern Guanacaste gave a short talk about the history of the place.

He said that in 1989, the 18,000 acres that make up Horizontes were donated to the Costa Rica National Parks Foundation and were to be managed by the folks in the Guanacaste Conservation Area. He went on to point out that the only way they would have taken the land was if it was donated for free. At the time, they were focusing on purchasing the remaining tracts of forest in northern Guanacaste and buying a cattle farm wasn’t in the budget.

After the meeting I kept thinking about what he said. The massive forest that’s full of wonderful creatures where I love going every chance I get, was once almost entirely pasture and it wasn’t that long ago. I was alive in 1989! When Horizontes was donated, I was sitting in my living room in New Jersey watching G.I. Joe cartoons. Now it’s a huge, amazing patch of tropical dry forest full of tapirs. Incredible.

While Horizontes is a World Heritage Site, it is not a national park. It’s designated as an experimental forest. This is a category of protected area that is specifically designed to involve the general public in science and conservation. That means that you are invited to visit. There are kilometers of trails to hike, routes for mountain biking, and places to stay if you want to spend a few days there.

You can find more information about booking a visit to this Costa Rican gem here.

About the Author

Vincent Losasso, founder of Guanacaste Wildlife Monitoring, is a biologist who works with camera traps throughout Costa Rica.