When I first made the move from the northern US to the tropics, it took my immune system a while to adjust. In my first four years south of the Tropic of Cancer (two in the US Virgin Islands, two here in Costa Rica), I contracted cases of undulant fever, dengue fever, a serious heat rash, a few cases of food poisoning, flu that felt more like malaria, and the piece de resistance, an intestinal parasite known here as la babosa, that lodged in my gut and grew and spewed to an ungodly two by five inches (it looks worse in metric, which is how it was recorded on the medical record– five by twelve centimeters). The ulcerating parasite was removed during emergency surgery and left a permanent zipper scar that runs north to south just to the right of my navel.

By that time, I wondered if I ever should have left the northern US, with its four distinct seasons and a solid stretch of sub-freezing weather that helped to keep all those pesky bacterial microbes temporarily at bay. Once I was plunged into the year-round warm weather I had often dreamed about, reality laughed at my untested immune system. Yet following the surgery, I emerged from the physical doldrums of the previous years a new man, with a new, beefed-up immunity to match. Aside from the to-be-expected occasional cases of grippe, I have lived three decades resistant to the maladies that once plagued me.

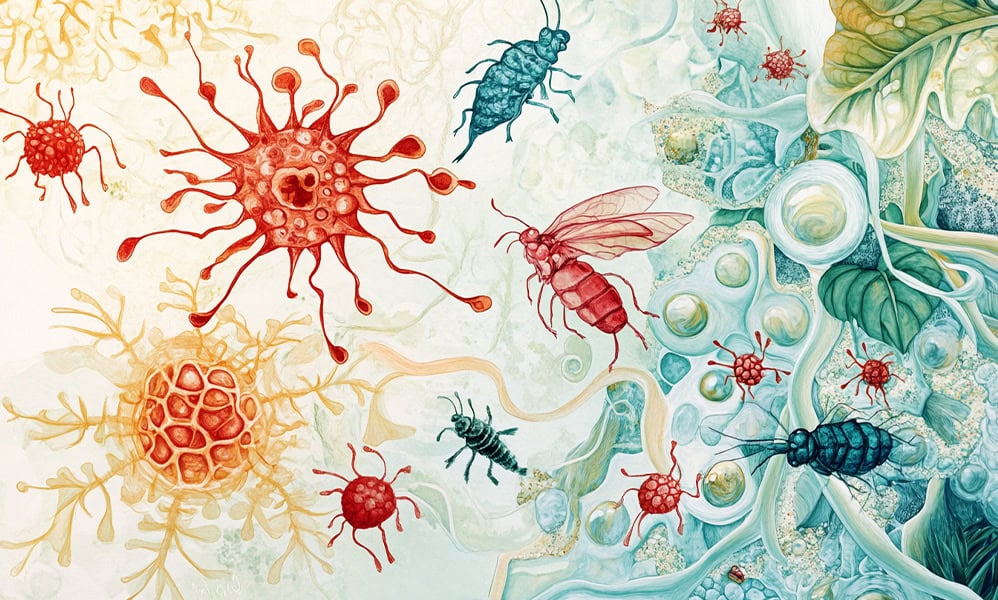

One ongoing malady I have never completely whipped is the common amoebic parasite or worm or whatever it is that makes me run to the bathroom thirty minutes after my breakfast and leaves me emptied out, with a growling belly and a dull headache. Ticos I know commonly blame lombrices; most dictionaries define lombrices as earthworms, but I think I would feel an earthworm burrowing through the pockets of my intestines. More likely they are roundworms or pinworms or hookworms or ascariasis or flukes. If it’s not a worm, than it’s likely a protozoa such as giardia, cyclospora or maybe entomoeba hystolytica.

I am clueless as to which I might have, or even how to correctly pronounce the protozoa, but I do know that I need to make a trip to the pharmacy– no prescription needed, at our pharmacies you can still get back room injections of anything from Vitamin B-12 for lethargy to ephedrine for an asthma attack. I always ask for the generic, 3 day, 6 pill regimen and they give me six hits of Nitazoxanida and the first day, two pills in, I feel better. I can eat without my nutrients being hijacked and visits to the bathroom are unrushed.

If only there was a pill to take for the damage left by the coloradillos. I spent the weekend on a farm in the Osa, that unspoiled corner of Costa Rica where nature and wildlife still rules supreme, a slice of old Costa Rica that has resisted overdevelopment. Coloradillas are tiny red mites, a pesky relative of spiders, scorpions and ticks. They are found in grassy fields, forests, green areas, along rural shorelines. They attach themselves to the skin with their claws and then inject their saliva. The saliva contains digestive juices that dissolve skin cells, which the coloradilla then eats. After feeding, the coloradilla sheds its skin and leaves a red welt.

While in the Osa, I spent time in grassy fields, forests, green areas, and along rural shorelines. So, a day later, when I look down at my ankles and scratch away at the red welts until they are on the verge of bleeding, it comforts me in some odd way to know that, endless itchiness aside, I was right there in the cycle of nature, contributing to the brief life of a coloradilla.