In many ways, Costa Rica is a victim of its own success. Its beautiful beaches, abundant wildlife, and stable democracy have made it an attractive destination for tourists, as well as expats, who over the years have descended on this Central American “utopia,” bringing with them disposable income and a “higher quality of life,” which includes an increased cost of living for everyone.

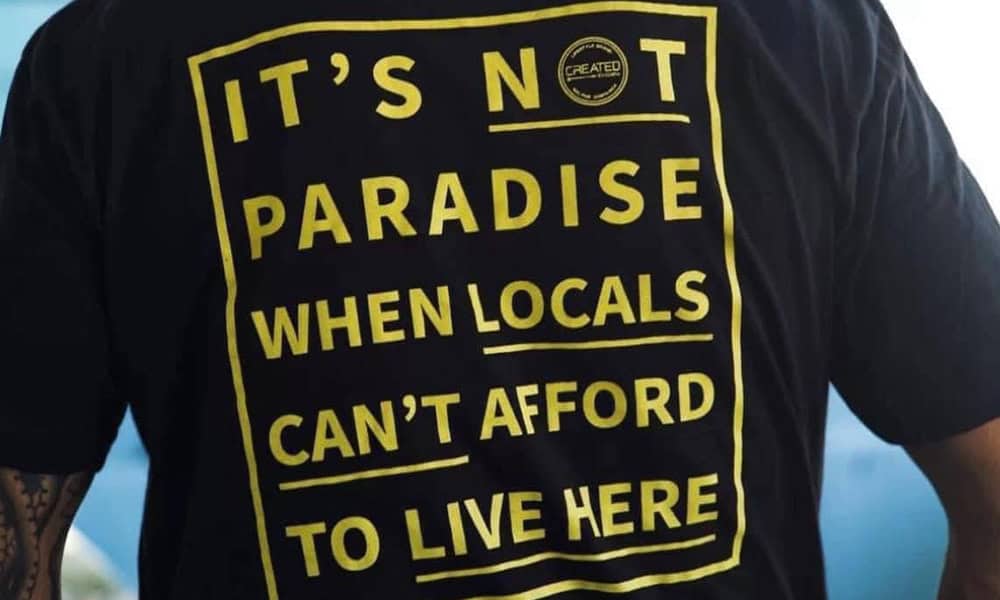

Inflation is felt around the world, but in Costa Rica, it has gone into hyperdrive since the pandemic, where rents have doubled, and the price of gas and groceries continues to rise with no sign of leveling out. The result is that many locals are having to move because they can’t afford to live in their own neighborhoods anymore.

The rising cost of living is most acutely felt along the Pacific coast, especially in tourism hotspots, such as Nosara, Santa Teresa, Manuel Antonio, and Costa Ballena. While tourism is a major contributor to Costa Rica’s economy, and although it supplies over 180,000 jobs to Ticos across the country, inflation has outpaced average wages, resulting in locals relocating further away from their places of work, where the cost of living is more compatible with their paychecks. The ramifications of this are longer commutes and less time spent with families, not to mention higher gasoline costs, as well as wear and tear on vehicles. In a nutshell, Ticos are being displaced, often from neighborhoods they have lived in their entire lives.

The term “gentrification” is often used to describe the phenomenon when the more economically well-off move into a lower-income neighborhood and consequently transform it by attracting new businesses, driving up rent, and often causing the locals to move to more affordable locations. Examples of this can be seen in neighborhoods such as Harlem in New York City or Casco Viejo in Panama. Guy Phillips, a resident of Dominical and former Assistant Secretary for Resources and Energy of California, suggests that the term “gentrification” is rooted in the idea of “gentry” or “higher” class and relatively greater wealth coming to an area.

This can lead to better schools, better access to healthcare, and other services, which on the surface sounds like a positive change. However, Dr. Phillips points out that one must look at the whole picture: if one group is moving in, another is pushed out, and historically, this has been white people displacing minorities from neighborhoods their families have lived in for generations. So, “gentrification” tries to put a positive spin on a phenomenon that doesn’t affect all people positively.

Others have used the term “neocolonization” to describe what is happening in Costa Rica. This conjures up images of European powers arriving to lands occupied by indigenous peoples and either outright enslaving the natives or subjugating them to the point where they lose connection with their cultural roots.

While this term packs a powerful rhetorical punch in the minds of the public, it can also backfire if people see it as hyperbole bent on manipulating others into accepting a political agenda. Ignacio Guerrero, owner of Soul Trip, a company specializing in acupressure, traditional medicines, and herbalism, has said that while the term “gentrification” overly simplifies the issue, calling people “neocolonists” for moving to a country they love isn’t exactly fair either. Dr. Phillips has suggested that “touristification,” or the conversion of an area to attract tourists, is a more accurate way to describe what is happening on the Pacific Coast. Regardless of the nomenclature, some Ticos feel growing animosity towards foreigners, whom they perceive to be the perpetrators of the negative impacts of the skyrocketing influx of tourists with foreign investments.

There is a palpable animosity in local communities towards foreigners, claims Ignacio Guerrero of Soul Trip. While some are vocal in their resentment, there are others who feel indignation but stay silent because they do business with foreigners and don’t want to sabotage their livelihood. Ignacio, who is Costa Rican, said that as a business owner, he hasn’t been hurt financially, but has had to raise his prices to keep up with the rate of inflation, which hurts him on an emotional level because he cares about the effect it has on other Ticos.

The effects of inflation are not felt as sharply by foreigners, who are generally more financially equipped to weather the storm of rising prices. In addition, Ignacio points out that this financial disparity makes it more difficult for Ticos to compete with foreigners when it comes to investing in properties. This imbalance is what many see as one of the principal causes of the rising costs of living.

In recent years, the shift of land ownership in Costa Rica from locally owned to expat-owned is the principal cause of anger some locals have towards foreigners. According to Climate Advocates Voces Unidas (CAVU), an organization that supports local solutions to environmental problems through visual storytelling, in a video they produced entitled “Los Senderos del Cambio” (“The Paths of Change”), 85% of coastal lands in Costa Rica are now owned by foreigners. Another video by The Center for Responsible Travel, called “The Goose with the Golden Eggs,” features Nino Rodrigues, a local from the Osa Peninsula, who explains how his father owned 1,000 acres of land in Cabo Matapalo, but sold it to a foreign investor for what seemed at the time to be a large sum of money.

After a few years, the money was gone, and Nino returned to the land, now a retreat center, to work as a gardener. Merlyn Oviedo, owner of Danta Lodge, states that this is a common story: local landowners, who often don’t have a strong grasp of how much property is worth, sell their land, buy a car and a small house with that money, and then see that money disappear in a couple of years. Meanwhile, the value of their old property appreciates, and the people who bought the land end up making a fortune.

To complicate matters, locals face further economic pressure from large-scale tourism projects, of which both foreigners and Ticos are involved. Dr. Guy Phillips points out that these are multi-faceted endeavors that include hotels, residential homes, restaurants, and other activities which have a self-contained commercial value and, if greenlit, will out-compete the local businesses in town. José Lino, former President of the Environmental Tribunal, agrees with this assessment.

In “The Goose with the Golden Egg,” he claims that large groups and multinational companies, who purchase land to develop resorts, will buy from large suppliers to minimize costs and maximize profits. In contrast, small and medium-sized businesses tend to do business with the local communities. So, Costa Rica, a country dependent on tourism, needs to think about what type of tourism they want to attract to the country. Do they want to bring in large hotel chains that give back very little to the community or smaller ventures that have the opportunity to provide jobs and stimulate local businesses?

Many locals also point to the increase in vacation rental homes as another culprit in the rise of the cost of living. Natalia Sanchez, a Costa Rican property manager, has been living in the Costa Ballena area for 20 years. She is concerned that the rise of Airbnbs, especially since the COVID pandemic, has replaced single-family homes, reducing a sense of community in places such as Uvita. According to a press release by EIN Presswire on August 22, 2024, “83.33% of the leading 30 Costa Rican investment properties employ a professional property management company or have a host who manages over five different vacation rentals.”

This suggests that larger vacation rentals are consolidating property management jobs and minimizing employment opportunities provided by small-scale hoteliers. Natalia states that there needs to be a clear plan regulador, or zoning plan, in these areas that limits the number of Airbnbs and protects local businesses. While she thinks that the local government is not doing enough to provide resources that the community needs, she also finds fault with the community itself for not being more organized and putting pressure on the local governments to provide these resources.

Local community leaders have suggestions on how to address these financial challenges and empower locals. Natalia Sanchez believes that petitioning local municipalities to offer services, such as English classes, can help locals develop skills to capitalize on the growing tourism industry in their area. Others have suggested that entrepreneurial seminars can encourage locals to keep and utilize their lands for the purpose of starting their own businesses.

Some families have shown this to be a financially successful model by offering tours on their properties in sustainable farming, chocolate or coffee production, and interpretive nature walks. Pilar Salazar, Co-founder of Bodhi Surf + Yoga, said that the community of Bahía Ballena has changed significantly over the years, but it isn’t all negative. She claims that when she first moved to the area from San José back in 2008, there weren’t many jobs, and the growth in the tourism sector has provided opportunities for locals. However, she mentioned that the growth has continued without restrictions, which is why the community needs a plan regulador to promote sustainable real estate development.

Pilar adds that change is constant, and communities need to adapt, which means that everyone with a voice should have a seat at the table and work together to form collaborative solutions. For instance, she states that if the rise in vacation rentals is having a negative impact on communities, both the local businesses and the Airbnbs should sit together to develop strategies to mitigate this issue.

Pilar suggests that communities such as Costa Ballena could benefit by not putting all their eggs in one basket and relying exclusively on tourism for the local economy, but rather focusing on developing additional projects, such as a marine research center or other endeavors that support the local economy and don’t alter the alma, or soul, of the area. Achieving these changes requires initiative. Pilar points out that people often say, “We should do something,” but what they

are really saying is, “Someone should do something.” It takes a single person in the community to motivate everyone to take action, so these leaders need to be identified and supported to get the ball rolling.

Foreigners who are concerned about what is happening to locals in their adopted country can also get more involved in the community, but unfortunately, locals and expats don’t always collaborate together due to perceived cultural differences or language barriers, and this can prevent them from achieving a common goal. Pilar Salazar points out that all — Ticos and foreigners alike — have a commonality, which is that everyone is benefitting from the beauty of these coastal areas, so it is everyone’s primary responsibility to preserve them.

Secondarily, she states that transplants to these areas (whether from another country or another part of Costa Rica) have a responsibility to the communities because, by moving there, they have stirred up the lifestyle of the longstanding residents. Therefore, Pilar said, it is important for business owners to provide opportunities for local workers, not just in terms of a paycheck, but also for personal growth, which allows them to develop skills and empowers them to pursue a career that brings fulfillment and a sense of purpose to their lives. She adds that ideally, if employers invest in their employees by providing transportation or, even better, setting them up with affordable housing, it will make the workers feel valued, which results in more commitment and higher morale in the workplace.

While expats may feel constrained due to their lack of citizenship, they too can help by not buying homes from large developers who have exploited local landowners. Tourists can do their part too by supporting small-scale local tourism. With all these ideas taken together, the displacement trend can start to reverse.

In Austin, Texas, a famously eclectic city that also saw a rapid transformation from the influx of migrants, the slogan “Keep Austin Weird” was used as a reminder of the importance of supporting local businesses and maintaining the city’s cultural soul. Costa Rica finds itself in a similar situation. Through community programs that equip locals with the skills to capitalize on the tourism industry, while simultaneously pressuring local governments to enforce plans that help protect communities from the pressures of touristification, Ticos and expats can join together to “Keep Costa Rica Local.”

Ryan Meczkowski is a Naturalist Guide and Founder of Simbiótica Adventures, which offers night tours and educational nature excursions in Uvita de Osa.

Email: cr.naturalist@gmail.com

WhatsApp +506 6132 9436

Website: https://www.simbiadventures.com