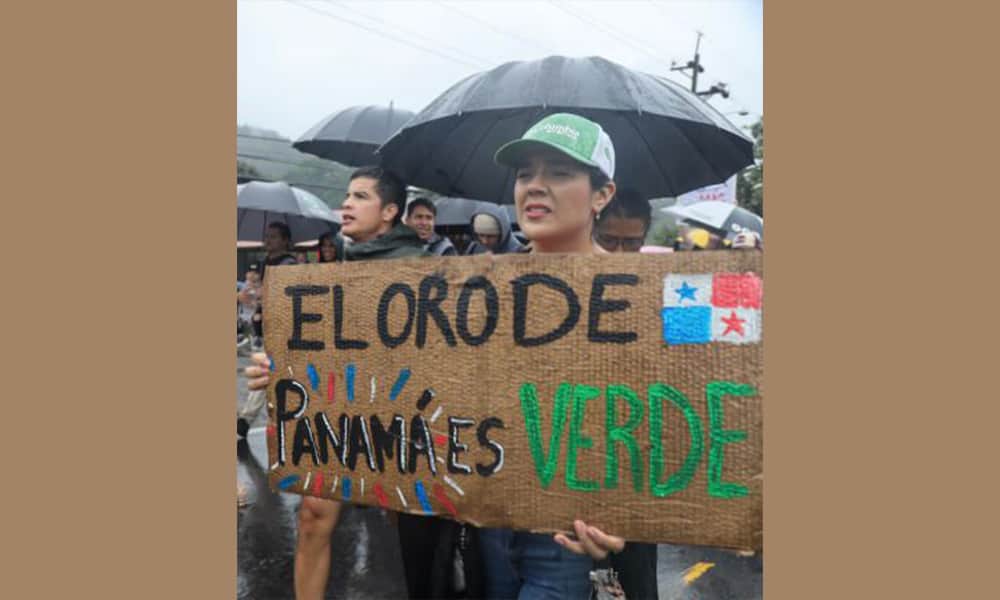

If you were traveling through Panama last November, you weren’t traveling far. Protests erupted, closing down streets, delaying supply chains, canceling travel plans, and virtually bringing the entire country to a standstill. The reason? Citizens expressing their displeasure with the government’s renewal of a contract with First Quantum, a Canadian mining company, extracting copper from an environmentally-sensitive area on the Caribbean Coast.

While some were concerned with income going to a foreign entity, others cited infringement on indigenous lands. However, the primary reason Panamanians took to the streets was out of concern for the negative impact the mine would have on the environment.

The situation eventually was resolved by the Panamanian Supreme Court on November 28th when it ruled that the contract was unconstitutional. While this was seen as a huge win for the environmental movement, some consider it a lost opportunity for Panama, citing the negative impact on jobs and the country’s gross domestic product (GPD).

This begs the question: in a world with increasing demands on finite resources, should Panama, a country rich in natural resources, stop relying on foreign capital and transition from a service-based economy to one that is reliant on sustainable industries such as ecotourism?

Panama doesn’t have to look far to for a successful model of an ecotourism-based economy. Costa Rica, their neighbor to the north, has shown that investing in natural spaces is a sustainable model that can be maintained for years to come.

Using Costa Rica’s example would be of particular benefit to Panama because they share many of the same ecosystems that range from tropical rainforests, dry forests, and mangroves in the lower elevations to cloud forests and páramo in mountain regions.

In addition, both countries share an abundance of biodiversity. This is in part due to the geographic position of the Isthmus of Panama, which connects the continents of North and South America, thus forming a literal land bridge in which wildlife from both continents freely pass through this narrow strip of land.

Furthermore, the ecological wealth of Panama is not restricted to its terrestrial destinations. Marine areas, such as Bocas de Toro, Coiba, and the Pearl Islands are known world-class diving sites. These combined factors make Panama the ideal location for exploring opportunities in ecotourism.

So, while Panama has the potential to develop its ecotourism sector, the question is does it have the support of the people to do so? Around the developing world, one can find myriad examples of “paper parks” – nationally recognized protected lands that don’t have the government funding to properly enforce and maintain the ecological health of the designated area.

This lack of financial support has made these places ripe for exploitation from activities that include poaching, timber extraction, and illegal mining. As Costa Rica has shown, community support is vital for sustainability projects to succeed.

When Santa Rosa was declared a national park in 1971, Costa Rica’s Ministerio de Ambiente y Energía (MINAE) had to decide what to do with 40 families illegally squatting on and degrading government land. Instead of kicking them out and having them find a new home, the government paid these people to relocate.

As described in David Rains Wallace’s book The Quetzal and the Macaw, which tells the history of the national park system in Costa Rica, this was a decision spurred by the actions of Mario Boza and Álvaro Ugalde, two university students at the time with a vision.

They knew that if ecotourism were to flourish in Costa Rica, it would need the support of the government, as well as the citizens, and kicking people off their land, even if the land didn’t belong to them, could create a backlash, fostering feelings of anger towards MINAE, and the government at large, thus endangering their vision of a greener future.

Locals were trained and provided jobs with the newly-formed national park, which was in need of park rangers, naturalist guides, and various administrative positions to carry out daily operations.

So by focusing on community-based ecotourism projects, in which the citizens could see a direct benefit to conservation in their daily lives, the idea of protecting, rather than exploiting ecosystems took hold. It didn’t happen overnight, but Costa Rica has become the model for how to successfully invest in sustainability.

In Panama, last year’s successful protests seem to suggest that not only the will, but also momentum, exists for ecotourism to succeed and the Panamanians are ready to look towards a greener future.

Of course there are some lessons to be learned to ensure that ecotourism doesn’t harm the very ecosystems it strives to protect. For example, Manuel Antonio National Park in Costa Rica is a victim of its own popularity. With its reputation for biodiversity, and its proximity to San Jose, the park draws in huge crowds, leading to added stress on the environment. This includes not only higher foot traffic, but also the infrastructure necessary outside the park boundaries to support increased demands.

Wildlife, which is not just confined to the national parks, depends on biological corridors to ensure healthy populations, so development can affect genetic diversity within these animal populations. Having a well-planned infrastructure in place to support a burgeoning ecotourism industry is extremely important. The Central African country of Gabon put aside 10% percent of its land in the creation of 13 national parks in 2002 for the purpose of creating a viable ecotourism industry.

This was a reasonable objective, since Gabon is home to unique and charismatic species such as mandrills, forest elephants, and western lowland gorillas, to name a few. Calling itself, “The Last Eden,” the country’s goal was to become the Costa Rica of Africa. However, in 2024 with a lack of accessible roads and trained tour guides (not to mention a coup d’état that occurred last year), Gabon has yet to see a return on their environmental investment.

Of course for a country to successfully pull off an ecotourism-driven economy, it is important to have a stable government. Here Panama has a lot to be optimistic about. The power of protest is a sign of a healthy democracy. Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs) and international donors, who support large environmental and conservation projects, are more likely to invest their capital in places where they know their money won’t go directly into the pockets of corrupt government officials and executives of large corporations who controlled the banana republics of Central America a century ago.

From a human-rights standpoint alone, the fact that Panama was able to use grass-roots energy to put an end to an environmental catastrophe, is a testament to growing optimism for democracy in the region and is an example for other Central American countries to follow (this can also be seen in Guatemala’s protests, ensuring that duly-elected President Bernardo Arévalo assumed office in January).

Central American studies scholar Jorge Cuéllar stated in an interview with the North American Congress of Latin America (NACLA) that Panama has shown other developing countries, not just in the Americas, but also in Africa and Asia, that the people have the power to stand up against foreign interests and actions that degrade the country’s natural resources.

So in demonstrating that citizens can affect policy through mobilization, Panama just might inspire a revolution. Ideally, the revolution will be green.

Article written by Ryan Meczkowski Founder & Naturalist Guide CR Naturalist Experiences