Three days after Revista Summa published its piece on the launch of Florida Ice and Farm’s new drink, “Spik Up,” Fabrizio Ureña, a radio producer and English professor, left a comment on the article’s webpage questioning the Costa Rica beverage giant’s name choice: The name ‘spik’ caught my attention given that, in informal English, it’s a word used to refer in a derogatory way to Mexicans and Central Americans. … it could be misinterpreted.

Ureña is involved with the program “GroovEnglish,” which is broadcast on Radio Nacional 101.5 FM and affiliated with the State University at a Distance (UNED) language center. The program’s purpose is to expose young people to the English phrases, slang and colloquialisms that make up the language of American rock ‘n’ roll.

Florida Ice and Farm brand manager Melissa Quirós Arroyo told business daily La República that the target market for Spik Up is teenagers aged 14-17, a plugged-in generation that wants to drink a soda with “a 100 percent digital DNA,” who, according to Quirós, would find Spik Up exciting and relatable.

“Let’s Spik Up,” Spik Up’s slogan, is more than the brand’s identity: It’s a hashtagable cry for free, youthful expression. Spik Up’s success as a brand depends on how “viral” it becomes. An Internet phenomenon for an Internet culture. Spik Up even has its own app: the “Spik App,” developed by the San Pedro-based web design company La Creativería in collaboration with Pulse Creative Technology and Madison DDB. Quirós described what the consumer was looking for, and what Spik Up would provide:

Today’s consumer is constantly searching for new flavors, sensations and consumer experiences. Spik Up fulfills these needs for an adolescent niche market. Representatives from Florida Ice and Farm, Pulse Creative Technology and La Creativería all declined to comment on how the name Spik Up was conceived and chosen.

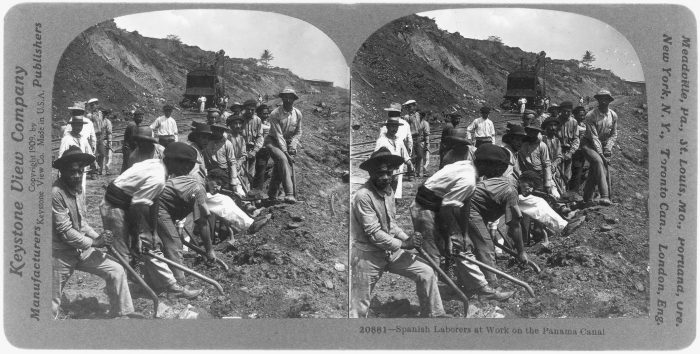

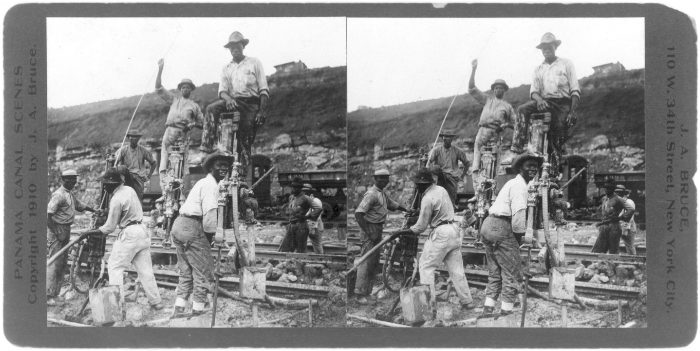

To understand the meaning of “Spik,” one must go back in time, but not physically far, from where we stand today: to Panama in the early days of the canal’s construction. This was the place The Saturday Evening Post dubbed “Spiggoty Land” in its March 14, 1908 edition.

“Spiggoty” is the ancestor of “spik,” and as Juan Vidal clarified in his 2015 NPR piece “Spic-O-Rama: Where ‘Spic’ Comes From, And Where It’s Going,” the term is older than the term “Hispanic.” A “spik” or “spic” was a canal worker, or other non-native English speaker, who struggled with the language. When confused, these workers would say to their bosses, “No spik’d English.”

These people were originally called “spigs” or “spiggoties” because of the way words rolled off their tongues. To the untrained ear, the “k” that ends “speak” rolls into the “d” that begins “de,” creating something like a “g” sound. “Spiggoty” was a bastardization of “spik’d,” which was twisted out of “speak de” itself.

Presumably, over time the workers slowed their speech to accommodate their bosses and avoid any misunderstandings. So the “g” in “spig” became the “k” in “spik.” How does history remember the men and women described by this word? From H.L. Mencken’s “The American Language,” published in 1919:

Spiggoty, of which spick is a variant, originated at Panama and now means a native of any Latin-American region under American protection, and in general any Latin American. It is Navy slang, but has come into extensive civilian use. It is a derisive daughter of ‘No spik Ingles.’ The Marines in Nicaragua called the natives gooks. Those of Costa Rica are sometimes called goo-goos.

That is the legacy of the word “spik,” a slur used to ostracize and demean the very laborers whose hands and sweat built the Panama Canal. Costarricenses and panameños who, when deemed too lazy, uncooperative and susceptible to yellow fever, wasting sickness, and malaria, were replaced in the “Silver Rolls” by the West Indian “Colón Man” of Charles Gadpaille’s labor recruitment ads. These three classes of men were all once called “spiks.”

Florida Ice and Farm Company’s reach in Central America is tentacle-like today, but the company began as a partnership between two West Indian ice harvesters: English-speaking brothers from Limón, who named the company after the Siquirres plantation where they cut and traded their product around 1908.

Florida Ice and Farm Company is a nexus point of Costa Rican commerce with significant stakes in tourism through its subsidiary, Florida Immobiliaria S.A., and commercial food production through its two largest divisions: Florida Capitales S.A., which finances the company’s bottling plants and regional operations, and Florida Bebidas S.A., the company that directs FIFCO’s product line through the manufacturing, bottling, and distribution of virtually every drink you can buy at major supermarkets, Musmanni bakeries (which FIFCO bought out in 2011), right down the line to every independent, nameless soda.

Insight into the high level of talent and intellect FIFCO employs to develop its brands comes as easily as a cursory run through LinkedIn. The faces of FIFCO’s brand marketing team are young, bilingual, often multilingual, and assumedly fluent in high and lowbrow American culture. They are fresh-thinking creative types.

Someone, somewhere in that high tower knows what “spic” means, and what it might mean for the name of a mass-marketed soft drink for Latin American consumers to come within one letter of that word.

Some words can’t be reclaimed and will always belong to the lands, tongues and circumstances which birthed them, no matter how ugly they may be. That is why you’ll never see a drink called “Coon Cola” on store shelves in the southern states of the U.S., or “Gook Grog” displayed at a market in South Korea, Thailand, Vietnam or the Philippines.

Whether it’s written “spig,” “spic” or “spick,” “Spik” is that kind of word. Because they trade in words and emotion – packaged in an enticement: “Drink me to feel …” – advertisers and corporations should choose their words very carefully. Buying power, the real power that each individual has, perceives in an instant. Before the shopper even considers why, a judgment is made: “How does _____ make me feel?”

Cas Ayala studied anthropology at the Boro Art Center in Metuchen, New Jersey. She lives in Curridabat.