MADRID – Leonor remembers the long corridor of the Spanish maternity ward where she saw her newborn daughter disappear in 1964, taken away by a nurse, like it was just minutes ago. The next day she was falsely told by hospital staff that her daughter had died.

Her baby was just one of tens of thousands of newborns who were snatched from mothers and fathers deemed politically dangerous to General Francisco Franco’s dictatorship by a network of doctors, nurses, priests and nuns, and given to other families.

Now four decades after Franco’s death on Nov. 20, 1975, the scandal over the “stolen babies” of the regime looks set to go unpunished.

“It was just a few seconds and she was dead,” said Leonor Sánchez Arroyo, a frail 73-year-old with a wrinkled face.

While she had doubts that her newborn had really passed away, she said she did not dare argue with the nuns who ran the maternity because in those days “the word of a nun had as much value as that of kings.”

Just 21 when she gave birth and with little schooling, she also did not ask to be given the remains of her newborn so she could organize the burial herself.

Nearly a half century later, her second daughter, Soledad Arroyo, now a journalist, saw a report on television about the theft of babies from that same clinic in Madrid.

The register of the O’Donnell clinic listed dozens of other deaths of newborns in just one month from unlikely causes, such as an ear infection.

It was November 2010 and the scandal over the stolen babies was only just breaking out in the open after decades of silence and whispered rumors.

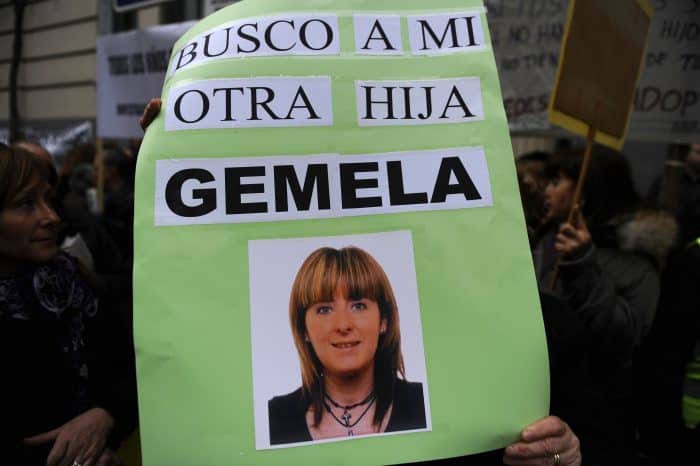

In vain, Soledad and her mother tried to search for the lost sister and daughter, attempting DNA matches with several people. Now, they help other people in the hope that they may be successful.

Up to 300,000 cases

The practice began after Franco came to power in 1939 following Spain’s civil war pitting Republicans against Nationalists loyal to the general, said Soledad who has written a book on the topic.

“The prisons were full of Republican women, and their babies were systematically stolen in order to ‘clean the race’,” she said. “Those babies were given to families who were in favor of the regime and who could not have children.”

The practice gradually extended to include the theft of newborns from poor families by doctors and nurses — many of them nuns — to adopted parents in Spain and abroad.

New mothers were often told their babies had died within hours of birth and the hospital had taken care of their burials.

Since the scandal emerged, some of the babies’ supposed graves have been exhumed, only to reveal bones that belong to adults or animals — or nothing at all.

Soledad said she has not found any evidence that the baby thefts were organized by the regime, but added it was “tolerated” by the government.

Estimates vary as to the number of children who were taken from their parents, but she estimates there could be up to 300,000 cases of baby snatching.

‘We want to know what happened’

As of 2011, only 1,072 criminal complaints regarding stolen babies have been examined and 30 percent were shelved, according to the Justice Ministry.

Spain has yet to come to terms with its civil war and Franco’s subsequent dictatorship — seen as a particularly dark chapter of its recent history.

Former crusading investigative Judge Baltasar Garzón in 2008 opened the country’s first criminal investigation into the disappearance of tens of thousands of people during the Franco era.

But he promptly had to drop it because it was seen to violate an amnesty passed in 1977 by political parties keen to put everything behind them and ensure a smooth transition to democracy after Franco’s death.

Associations want the government to set up a DNA bank that would allow potential matches between those who were stolen babies and their biological families — a proposal backed by the main opposition Socialists.

Meanwhile, Ángel Casado, of the Adelante Bebés Robados association (“Onwards Stolen Babies”), would like the government to pass a law that recognizes them as victims of the regime.

Spain’s conservative Popular Party, in power since 2011, has never condemned the removal of newborns from their mothers by the regime and Church documents about the affair remain inaccessible.

“We are not seeking financial compensation. We want to know what happened to these children, that they know their true identity,” said Soledad Luque, the head of another association of stolen babies.