Julio Eduardo Laínez Somoza, who was born in El Salvador but left his mark as an extraordinary photojournalist and painter in Costa Rica, died Friday evening at 76, following a long illness.

Funeral services were held Saturday, June 14, at the Iglesia Don Bosco in southwestern San José. He was buried in the Cementerio de Obreros.

Laínez, born on June 16, 1937 in San Vicente, El Salvador, moved to Costa Rica in March 1964 at the age of 27. According to his daughter Ana Margarita, Laínez set out for Costa Rica “with a suitcase full of dreams – not the American dream, but the dream of building a family.”

In Costa Rica, he had his sights set on educator Margarita María Murillo Montoya, and the two were married on June 19, 1964. They had three children: Julio, Ana and Lourdes. Laínez was a doting father, and an adventurous spirit who passed on to his children a love of camping and exploring. According to Ana, as an amateur geographer Laínez could pinpoint “every mountain in every corner of this, his adopted country.”

From 1966 to 1980, he operated a photo studio on Paseo de los Estudiantes in San José called Laínez Photo. He joined The Tico Times in 1983, continuing with the weekly newspaper until his retirement in 2003.

Former Tico Times publisher and editor-in-chief Dery Dyer called Laínez “a master photojournalist.”

“He had the heart of a journalist and the soul of a poet,” Dyer said.

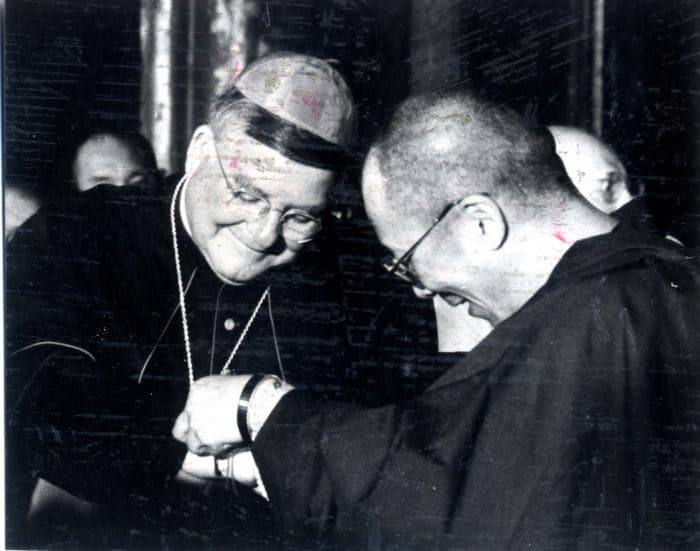

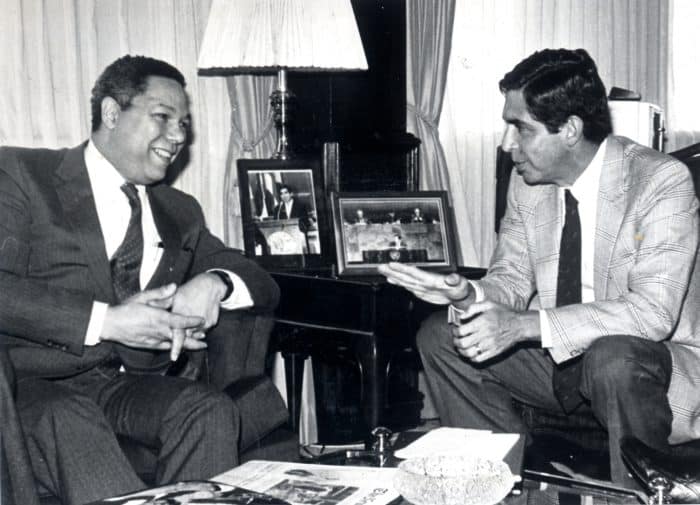

His photos – until the very end of his career taken with film cameras and painstakingly developed in the darkroom – all carried his distinctive signature. They invited a second and third look. Whether of angry faces in a demonstration, pensive presidents, natural disasters or a field full of sparkling spiderwebs, they always offered the reader something more. Beautifully composed, they told stories of their own that invariably enhanced whatever was being reported.

Laínez’s photos were quiet, even humble. They were never flashy or gimmicky, never tried to overshadow, overwhelm or call attention to themselves. They could stand alone, but they were always in service – to the writer, and above all, to the reader.

In that sense, Laínez’s photos reflected his personality. “He was quirky, individualistic and completely professional; he had no need to show off his incredible talent,” Dyer said.

Those who worked with him say he had an elfish, twinkly sense of humor that often found its way into his pictures – schoolchildren struggling to stay awake on the first day of school, an alley cat helping himself to the lion’s meat in the zoo, a tree frog meeting his ceramic friend in a garden.

Laínez hated mundane, routine assignments, resisting them with “mulish stubbornness that frequently drove his editors to distraction,” according to Dyer. But he would quietly go out on his own and come back with astounding pictures. And he was often first on the scene when something exciting was happening. Laínez captured the first dramatic photos of the collapse of the old bridge at the La Paz Waterfall in October 2003, and was first to document the aftermath of several volcanic eruptions. His photos of the damage from the series of earthquakes that were causing the mountain town of Puriscal to slowly fall apart in 1990 took readers directly into the drama.

In 1986, when a 2-kilometer clandestine airstrip was discovered on the Santa Elena Peninsula in northern Costa Rica – used to supply the southern Contra front in Nicaragua’s civil war – Laínez was the first journalist to photograph it, and his pictures appeared in a Tico Times investigation published Sept. 26, 1986, and in several subsequent editions.

At official events, Laínez was famous for finding the unique angle. While other photographers were jockeying for position in the same space, Laínez could be seen dangling from a nearby scaffold or trespassing on someone’s balcony.

He was also famous for cheerfully ordering presidents and other dignitaries to pose for him; while the rest of the pack was respectfully settling for the usual boring official lineup, Laínez would appear and shoo the big shots into the poses he wanted, invariably getting them to laugh and look human in the process. The VIPs all loved him for shaking up protocol.

During his career, Laínez also worked at La República, La Hora and Prensa Libre. He was a die-hard Saprisista, and passionately collaborated with the Revista Mundo Saprisista and Sol y Sombra.

After retiring, Laínez was able to devote himself full-time to his favorite hobby: painting. He studied watercolor with cartoonist Arcadio Esquivel and became an accomplished artist. According to Ana and Lourdes, he “captured details that others never perceived.”

Arcadio recalls that Laínez belonged to a group of artists in San José who met every weekend to paint “the corners of San José” under the municipal program Paisaje Urbano. Three years ago, he displayed his work, which Arcadio described as “going beyond realism,” at an exhibition in the Casa de la Cultura Popular José Figueres Ferrer, one of several photography and art exhibitions in which Laínez participated. He also taught at the Escuela Casa del Artista Olga Espinach Fernández.

“He brought photography into his paintings,” Arcadio noted.

In 2012, Laínez’s daughter Lourdes was married in the same church as her parents, the Iglesia Santa Teresita, and Julio and Margarita María decided to renew their wedding vows. This Thursday would have been the couple’s 50th wedding anniversary, and Monday would have been Laínez’s 77th birthday.

Julio Laínez is survived by his wife, Margarita María Murillo, his sister, Lourdes, brothers César and Carlos, and children Julio César, Ana Margarita and Lourdes.