A year ago these writers warned that Nicaragua was making noise about reclaiming from Costa Rica its former northwestern province of Guanacaste. No one took the threats seriously. Nor did they give much credence to related reports about Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega’s aspirations to build a new inter-oceanic canal on the San Juan River with the financial support of Iran and China. The southern bank of the San Juan River borders Costa Rica and passes through the Guanacaste territory.

The implications of a Nicaraguan rival to the Panama Canal, if realized, could be very serious. Friendly Panamanian authorities can interdict unsavory cargo. The San Juan River, on which the new canal would be built, has already aptly been christened “the drug path.”

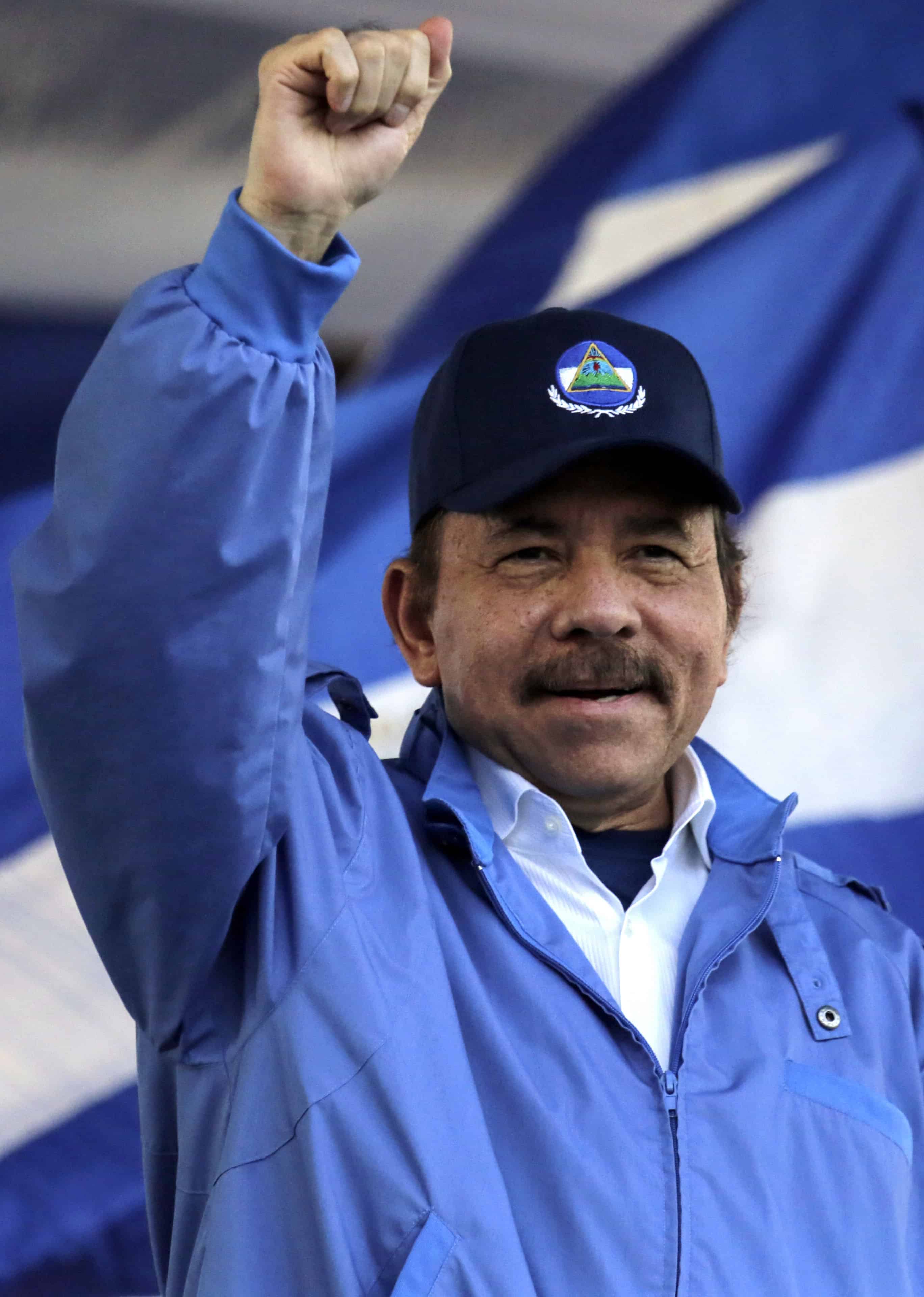

While the United States is preoccupied with economic problems, scandals, Washington gridlock, the ongoing bloodshed in Egypt, the civil war in Syria and Iran’s well-masked desire to obtain nuclear weapons, events in Central America have gone under the radar. Ortega threatened a few days ago to appeal to a world court to “recover” the Guanacaste province.

What is going on? Are we facing in our strategic backyard “an act of ignorance,” as Costa Rican Nicoya Mayor Marco Antonio Jiménez called Ortega’s demand?

Or do his threats bode serious potential future conflict? Former Nicaraguan Foreign Minister Francisco Xavier Aguirre Sacasa appears to think the former. As he recently told The Tico Times, “Every five years or so Nicaragua and Costa Rica clash over the San Juan River.”

However, it’s not just the San Juan. In 2010, Costa Rica launched a complaint to the International Court of Justice over Nicaragua’s violation of its wetlands.

This did not happen in Guanacaste, but rather along the northeastern Caribbean coast. Two years ago, the world court issued a ruling that blocked Nicaragua from entering the disputed territory.

As in the case of Polish-Russian relations, the historical legacy helps to partly explain the origins of these present conflicts. A year ago, when we reviewed the ongoing conflicts over Guanacaste with a leading Costa Rican historian, it became clear that they hark back to 1824 when the people living in that province elected to be part of Costa Rica. This appears to have been accomplished through legal means.

Ortega has a different view, however. He believes that Costa Rica obtained the province because of its role in defeating and expelling U.S. soldier of fortune and mercenary William Walker and his followers. Walker had attempted in 1856 to incorporate Nicaragua into the U.S. as a slave state. To Ortega, it was the Costa Rican role in defeating Walker “that has been the source of Costa Rica’s political ambitions to dominate this region including the strategically important Río San Juan and Lake Cocibolca.”

Naturally, there is an economic aspect to the Guanacaste dispute. Searching for answers along the old Nicaraguan-Costa Rican frontier, we determined from interviews with officials on both sides of the border that the Sandinistas’ 2011 dredging of the river, led by “Comandante Cero,” Edén Pastora’s nom de guerre, was related not just to possible canal building activity, but to the discovery of oil resources both on the Atlantic and Pacific side.

So what should we make of the present dispute? One has to recognize that Ortega’s Nicaragua is not the same country as it was in the 1980s when he was trying to build a Leninist-oriented regime. Yet his association with rogue states like Cuba, Iran and Venezuela is worrisome. And the recent, still not fully explained deliveries of missile parts to North Korea from Cuba, which were interdicted on the Panama Canal, dictate that the U.S. must aid in resolving potential conflicts between Nicaragua and Costa Rica.

Dr. Jiri Valenta is a long-standing member of the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations in New York City. His wife, Leni, is the CEO of The Institute of Post-Communist Studies and Terrorism.