On Aug. 7, the peal of church bells throughout Costa Rica heralded the news: The five Central American presidents had signed a peace agreement in Esquipulas, Guatemala, to put an end to civil wars in the region. The news was greeted in Costa Rica with an outpouring of pride and optimism that Central America had taken its destiny into its own hands after years of serving as a Cold War battlefield.

The agreement provided for the end to hostilities, the disarming of rebel groups throughout the region, free elections and the creation of international verification procedures. For weeks leading up to the Esquipulas meeting, the second peace talks in the Guatemalan city, Costa Rican diplomats had been telling the press that the signing of the agreement was imminent.

Many, though, didn’t believe such a thing was possible. The administration of U.S. President Ronald Reagan opposed the agreement because it would disarm the Nicaraguan Contra rebels struggling to unseat the leftist Sandinista government, the “freedom fighters” who Reagan had vowed to support to his last breath.

At the time, the U.S. Congress had cut off military assistance to the Contras, and Reagan was seeking $400 million in new aid to the rebels. The prospect of signing the agreement was rightfully seen as a message to the U.S. administration to keep the lethal-assistance spigot closed.

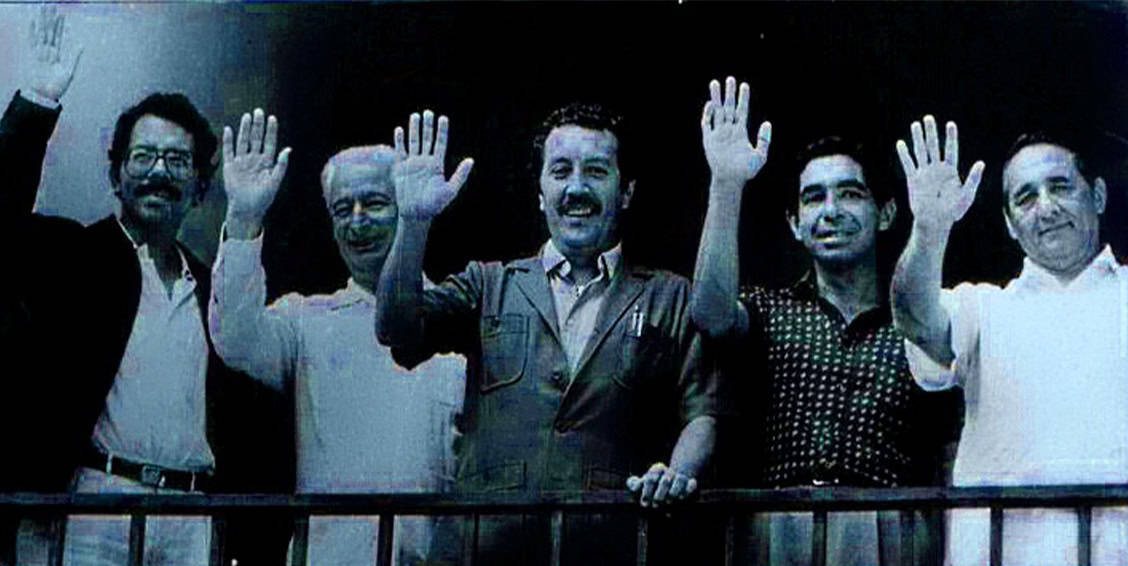

So in terms of the conventions of geopolitics, many assumed that the five Central American presidents, Oscar Arias of Costa Rica, Vinicio Cerezo of Guatemala, José Azcona of Honduras, Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua and José Napoleon Duarte of El Salvador, could not, even collectively, thwart the will of the United States, the region’s principal hegemon.

The Salvadoran and Honduran presidents were thought to be particularly vulnerable to U.S. pressure to decline to sign, Duarte because of the U.S. military assistance in fighting the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, and Azcona be-cause of the massive U.S. aid to the country serving as the principal base for the Contra’s fighting force.

Pressure on these two presidents by their biggest benefactor, so went the conventional wisdom, would scotch any peace agreement. I remember getting a call from a correspondent from a major U.S. publication about a week prior to the meeting in Guatemala asking what I thought the odds were that the presidents would sign. I responded that the Costa Ricans were saying that all indications were the accord would be signed.

His rather jaded response: “I doubt they’ll even meet.” Meanwhile, in Washington, the fate of the lethal assistance to the Contra rebels was being debated. The Democratic-controlled Congress had cut off assistance to the Contra rebels, largely as a result of the scandal that erupted the previous year, after U.S. officials and private surrogates had been caught trading arms to Iran and funneling the profits to the Contras.

Despite the fallout from the so-called “Iran-Contra Affair,” Reagan was applying pressure on Congress to reopen arms supply lines to the Nicaraguan rebels, and to that end, the administration had entered into negotiations with House Speaker Jim Wright. The two sides came up with a peace plan of their own that in many of its provisions mirrored the so-called Arias peace plan.

But there was a hitch: If the Sandinistas did not hold free elections outlined in the plan within six months, Congress would automatically approve the renewal of lethal assistance to the Contras.

Much to the chagrin of those in Congress and elsewhere, who thought that aid to the Contras ought to be permanently cut, Wright went along with plan, and jubilant Contra supporters, confident that the Sandinistas would not hold elections in such a timeframe, thought they had pulled one over on the House speaker.

Much later, after Wright resigned his speakership and the House for alleged ethics violations, he gave an interview to U.S. broadcaster Larry King, in which King asked him about his role in bringing peace to Central America.

Wright described the negotiations he had with the Reagan administration over the so-called Reagan-Wright plan and said that as his talks with Reagan’s people proceeded, he gave a call to his friend, Arias’ chief of staff – the Costa Rican president’s brother, Rodrigo – and asked about the progress of the peace negotiations in the region.

According to Wright, Rodrigo Arias responded that the five Central American presidents had arrived at an agreement and appeared to be ready to sign. In his Texas drawl, Wright told King that he believed that by signing the Reagan-Wright plan he could “give the negotiations in Central America a push.”

In effect, while Republicans thought they had pulled one over on Wright, the wily House speaker, by virtue of knowing what was happening on the ground in Central America, had out-witted the administration, which, apparently unknowingly, gave its tacit approval – especially to Duarte and Azcona – for the signing of the Esquipulas Accord.

Why not sign an agreement among Central Americans whose provisions appeared to have the stamp of approval of the U.S. president as evidenced by the similarities between the Central American plan and the Reagan-Wright plan?

Many years later, I asked Rodrigo Arias to confirm that Wright had given the Central American’s peace plan “a push.” He told me with a smile, “Así es.” “That’s it.”

When news of the Esquipulas II Accord broke, much of the world didn’t seem to know what to make of it. After all, an agreement between presidents from five tiny, Third-World countries firmly in the sphere of influence of the U.S. couldn’t trump an accord made between a U.S. president and the speaker of the House of Representatives – or could it?

In fact, it did, because in the end, Arias’ view that Central America’s difficulties were political, not military, and correspondingly the solutions ought to rely on political process, not military might, was borne out. Arias had the audacity to seek a protagonist’s role for himself and his fellow Central Americans in shaping the future of their own countries and that of their region.

But as emblematic as it was as an expression of Central America’s desire for self-determination, regional leaders must admit that Esquipulas II has fallen short of its initial promise. The centrifugal forces that keep countries in the region from consolidating stable democratic institutions have proven strong enough to outlive the Cold War as demonstrated by the 2009 coup in Honduras and fraud-ridden municipal elections in Nicaragua in 2008.

Also, the great hope of democratically elected governments free to express the desires of their people for peace and prosperity has been undermined by seemly-entrenched corruption and violence throughout the region.

In the post-Cold War, globalized, interconnected world, challenges of stemming the tide of these chronic problems ought to keep the Esquipulas II church bells ringing for years to come. In effect, while Republicans thought they had pulled one over on Wright, the wily House speaker, by virtue of knowing what was happening on the ground in Central America, had out-witted the administration

John McPhaul worked as reporter and assistant editor of The Tico Times from 1981-1987.