The United Nations Arms Trade Treaty goes into effect this Thursday, on Christmas Eve. The treaty covers tanks, armored combat vehicles, large-caliber artillery, combat aircraft, attack helicopters, warships, missiles and missile launchers, as well as the vast trade in small arms. The landmark ATT, which will be the first international agreement to regulate the world’s $85 billion arms trade, has its roots in the civil wars that scarred Central America in the 1980s.

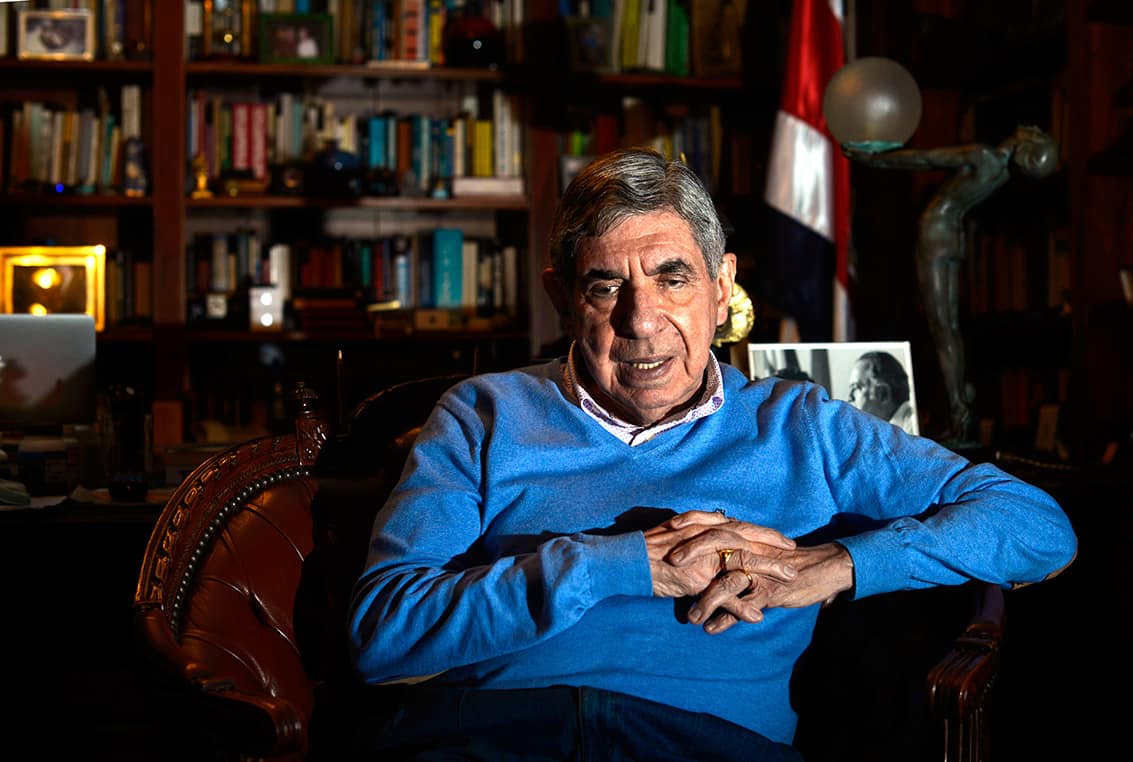

Witness to the destructive impact that an influx of weapons had on the conflicts that raged in the isthmus, Óscar Arias, former president of Costa Rica (1986-1990 and 2006-2010) would go on to play a key role in building an international coalition to support an International Code of Conduct for arms sales that eventually became the ATT. The Tico Times sat down with the former president at his San José home to speak about the genesis of the treaty and its journey to ratification and implementation.

When Arias assumed the presidency in 1986, he said that he wanted to try to insulate Costa Rica from the conflicts raging across Central America, especially the Sandinista revolution and Contra War to follow in neighboring Nicaragua.

“It was a proxy war where the superpowers [the United States and the Soviet Union] supplied the weapons, and we Central Americans the blood,” Arias told The Tico Times.

In the case of the United States, some of the weapons entering the region were legal arms sales, but in scandals like the Iran-Contra Affair, the Reagan administration illegally funneled weapons to Contra rebels in Nicaragua.

“After those conflicts ended, the weapons stayed behind. Warriors became gangsters. There were entire generations lost in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, which are among the most violent places in the world today,” he said. “Seeing this violence spread [after the wars ended], I became increasingly concerned about the unchecked flow of weapons,” Arias said.

After his first term as president, Arias, who would win a Nobel Peace Prize in 1987 for his efforts in negotiating an end to the region’s wars, started the Arias Foundation for Peace and Progress. The foundation began drafting a code of conduct for international arms sales. When the idea was discussed during a meeting of several Nobel laureates in New York in 1997, consensus grew for the need to curb the flow of weapons into conflict zones around the world. Other nongovernmental organizations signed on to support the plan, and when Arias assumed his second term as president, Costa Rica submitted the treaty to the United Nations in 2006.

“I never imaged that seven years later it would be approved,” he said.

The ATT prohibits the legal sale of weapons to conflict zones. So far, 154 countries have voted to adopt the ATT and 60 have ratified it, including Costa Rica in 2013. The United States is a signatory to the agreement but has not ratified it.

“There will be greater control over the buying and selling of weapons [in Central America]. There won’t be an open market like today,” Arias said.

The Nobel laureate said that while Latin America would also see benefits from the ATT, the lack of active military conflicts in the region outside Colombia would limit its immediate impact here. Countries in Asia and Africa, Arias said, would be the greatest beneficiaries from the curbs on legal arms sales.

Latin America has been largely spared the kinds of conflicts that sparked Arias’ initial concern in the arms trade. Instead, Arias said that he was more concerned about the growing number of countries in the region arming themselves despite what he said were more pressing issues for their people.

“One of the things that most offends me in Latin America is the buying of weapons. Venezuela buys weapons when there is no need, and their country is in an economic crisis that’s the worst in Latin America,” he said. Arias had similarly harsh words for Brazil’s decision to purchase more than $4 billion in military hardware — by far the greatest in Latin America, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, which tracks arms sales — despite a stagnant economy and the world’s worst inequality.

Peace pays dividends, Arias said. “Costa Rica can show the rest of the world what is possible. Instead of buying a tank, you could build a hospital; instead of buying a fighter jet you could lay 50 kilometers of highways. It’s obvious.”