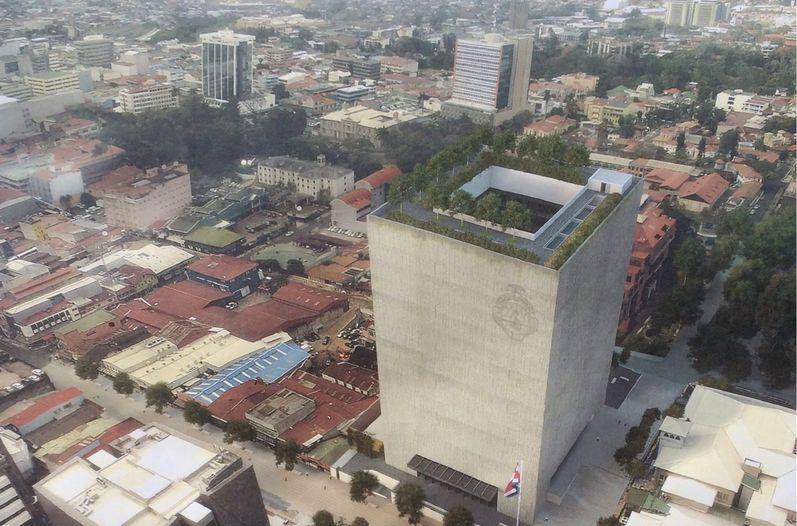

Architect Javier Salinas’ plan for a looming, concrete tower to house Costa Rica’s Legislative Assembly in downtown San José seems to get more criticism the closer the project gets to breaking ground.

In January 2013, Salinas won a contest to design a replacement for the current building, which health officials have ordered closed on numerous occasions. His first design had to be scrapped because the cost to build it was too high. The new plan — for a 17-story “concrete monolith,” as Salinas calls it — has come under a storm of criticism since its unveiling in March 2015.

San José residents and fellow architects have expressed doubts regarding the building’s design and functionality, singling out potentially sky-high energy costs and interrupted views for neighboring buildings.

Writing for the Costa Rican newspaper El País, Marité Valenzuela, a city councilwoman from San José’s Carmen district, offered up a harsh critique of the building design.

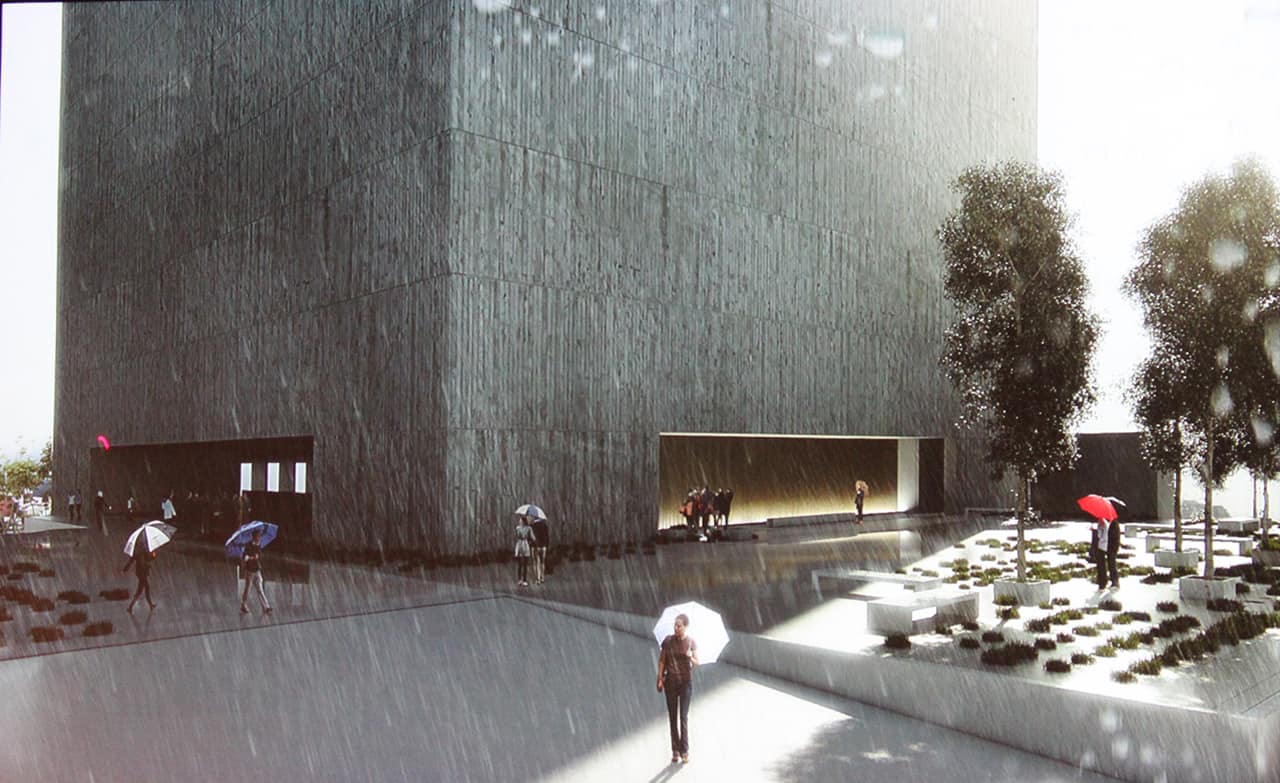

“This building, which looks more like one of those concrete trash cans you see here in the parks, projects images of rejection, separation and inaccessibility to people that isn’t in accordance with the high-reaching, democratic aspirations of our country,” Valenzuela wrote.

At a roundtable conversation at San José’s Véritas University last Thursday, Salinas defended his project while fielding questions from fellow architects and students at the university’s architecture school. After scrolling through a slideshow that included pictures of the Eiffel Tower and the Great Pyramid of Giza, Salinas came to a slide with an image of one of Costa Rica’s iconic stone spheres with the word “Solidarity” over it. Salinas said his building is a symbolic ode to Costa Rica’s democratic solidarity.

“Roots are another symbol that are expressed in this building,” he said. “For such a small country we have great pride …. This new Assembly is meant to represent all the citizens of this country.”

In local news stories and on social media (there’s even a “NO to the new Legislative Assembly building” Facebook group), many have said that the windowless building does not evoke democracy. Critics also say natural light and ventilation in the building will likely be minimal.

Salinas said Thursday that the patio on the top floor will receive plenty of sunlight, and opens downward like a well dropping 70 vertical meters. He also showed photos of angled divots in the new design, which he released in March 2015, which he said would provide air circulation.

“Everything is calculated in regards to sunlight and ventilation coming into the building,” he said. “We worked with a team of specialists to do all the scientific steps required to make sure there would be enough natural light and air.”

Salinas’ original design was to be made mostly of glass, but the high cost and lack of needed permits sent him back to the drawing board at the beginning of 2015.

In the redesign, the exterior would be made entirely of concrete walls, which Salinas said is a much cheaper alternative.

Julio Cedeño, an engineer whose company Novatecnia is supervising the construction project, defended Salinas at Thursday’s event, saying he has limited resources to work with.

“There’s an economic limitation here,” Cedeño said. “It’s not like Salinas and his team have a blank check to work on the design.”

Bruno Stagno, founder of the Tropical Architecture Institute and a former professor of Salinas, took part in the roundtable discussion Thursday. He said his doubts stemming from photos he saw in the media were reaffirmed during Salinas’ slideshow presentation. Stagno said a building made entirely of concrete is a bad match for Costa Rica’s tropical climate.

“Concrete is not going to work for you,” Stagno told Salinas. “In climates where we don’t have much variation like in the Central Valley, buildings don’t need more insulation. What they need is shade to make sure the sun’s radiation doesn’t bear down on them. In this, the sun is going to heat up the walls and this heat is going to always be transmitted inside.”

He added that the “well” that allows sunlight into the building will remain dark for most of the day.

The project, which is being primarily financed by the Bank of Costa Rica, is set to cost ₡52 billion, or $97.3 million, according to a Legislative Assembly press release. In terms of layout, the 50,000-square-meter building consisting of 17 floors, in addition to four basement floors. It will house offices for the country’s 57 lawmakers, an assembly room, and offices for each political faction.

Now that the checklist of permissions from a litany of state institutions is nearly complete, construction is supposed to begin in the next few weeks and is expected to conclude in 2018.

The only approval that is still up in the air is that of the National Technical Secretariat of the Environment Ministry (SETENA). Cedeño said at Thursday’s debate that developers expect SETENA to sign off on everything in the very near future, possibly as soon as this week.

Residents like Valenzuela have accused Salinas’ firm of being overly secretive about the project. She said no one really knows if certain permissions, like those required by the Health Ministry, are still pending because both the government and the developers are staying quiet.

“The public still has no idea what is going on with this building,” Valenzuela told The Tico Times. “The developers have been keeping information back and that’s unconstitutional.”

Architect Salinas said Thursday that contractual details restrict what information he can release to the public.

“I can’t give all the information because now is not the time to divulge all of that,” Salinas said. “Soon everything about the project will be out in the public but right now we’re limited in giving out information.”

Cedeño from Novatecnia said his company is working with Salinas to be more efficient in providing updates about the project’s development, saying they had begun putting an emphasis on transparency.

Fellow architect Álvaro Rojas, who presided over the jury that ultimately selected Salinas to do the project, also expressed his concerns with Salinas’ plan on Thursday. Like Stagno, Rojas taught Salinas at Véritas. He said he has told his former pupil that he worries about the lack of shade and the building’s massive size that could block views.

“Javier chose the symbolism of solidarity and democracy, but this sacrifices other symbols important to our country and ends up blocking the view,” Rojas said.

Rojas poked fun at Salinas’ allusions to some of the world’s greatest monuments in his slideshow presentation, saying that philosophical and theoretical emphases like solidarity and democracy can lead to oversights in more practical purposes.

Despite his doubts, Rojas appeared to lend his support to his former student.

“Even the pyramids of Egypt and the Eiffel Tower were under scrutiny when they were being built,” Rojas said. “Hundreds of years later people worship them. I’m sure the same thing will happen with Javier’s building.”