WASHINGTON, D.C. – As the presidents and foreign ministers of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala prepare for Friday’s White House roundtable with President Barack Obama, experts here met to discuss how to stem the influx of Central American children that has overwhelmed U.S. border officials, sparking a humanitarian crisis.

Rubén Zamora, El Salvador’s envoy to the United Nations, shared the podium with Doris Meissner, founder of the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute, at a July 16 panel organized by Washington’s Inter-American Dialogue.

The two, speaking before a packed audience that included officials from a dozen embassies, claimed that the crisis cannot be blamed on lax border enforcement – despite the rhetoric many Republicans and even some Democrats in the U.S. Congress are spouting.

“The argument that the U.S. Border Patrol is inefficient is absolutely wrong. The Border Patrol is the most efficient thing I’ve ever seen in the United States,” said Zamora, who served as El Salvador’s ambassador in Washington before being reassigned to New York earlier this year as his country’s envoy to the United Nations.

“They know when the people are coming. There are 40 TV screens along one section of the Río Grande alone, and as soon as there’s movement, all of them move into focus and can detect immediately what’s coming,” Zamora said. “When I was ambassador here, I asked the immigration people how they measured that migration from El Salvador was on the increase, and they said it was because they were catching more and more people every day.”

Hondurans comprise the largest group of kids (followed by Salvadorans and Guatemalans) among the nearly 58,000 unaccompanied minors who have showed up at the U.S-Mexico border since October. The presidents and foreign ministers of all three countries will press the Obama administration this week for more aid to stop the unprecedented influx.

Meissner, who was commissioner of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service during the Clinton administration, said the issue of unaccompanied minors at the U.S.-Mexico border is not new.

“Migration emergencies have happened before, and will happen again, but that doesn’t make it any easier to deal with,” she said. The problem now is that the average wait time for a child migrant to appear before a judge is 578 days. At the same time, funding for immigration enforcement programs has jumped by 300 percent in recent years, while the money available for hearings has risen by only 70 percent.

“If you’re coming from Mexico or Canada, the enforcement officials can ask you questions but you can be voluntarily returned. That is not the case with other countries,” she said. “Special protections have to do with the fact that children are vulnerable. They are much less likely to understand the legal options available to them, so they cannot be returned voluntarily to their home countries in the way adult migrants can. They are also not allowed to be subjected to expedited procedures.”

Meissner said that 82 percent of the kids who have crossed the border are now in the care of either parents or close relatives.

“What we have on the southwestern border is young people coming to turn themselves in, not evade enforcement,” she said. “They’re coming to find an agent to bring them to a Border Patrol station so these proceedings can begin.”

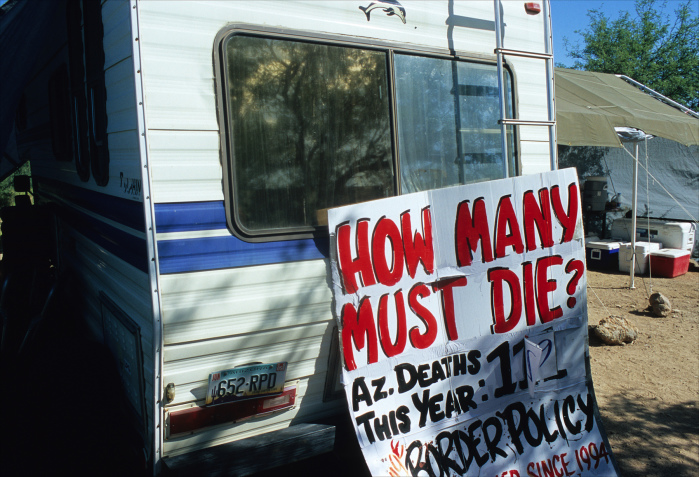

Zamora suggested that the real reason the kids are coming is the dramatic rise in gang violence throughout the northern tier of Central America.

“Gangs create a very serious problem on the peripheries of big cities, where they control the territory. They decide who lives and who doesn’t,” he said. “Let’s say a 12-year-old boy sees the gangs approaching him, and telling him, ‘Work for us or we’ll kill your mother.’ What’s he going to do, move to another place? Usually, these are poor people. What are the alternatives? They know they have a relative in the U.S. who is ready to accept them, so they go.”

Another factor is the improving economic conditions for Central Americans who have already migrated to the United States years ago.

“The father or mother has special status in the U.S., but they left their child in El Salvador. Now they have the capacity to have the kids live with them in their own home,” he said. “What father wouldn’t ask for his own child? The upward mobility of our community has created the conditions for that phenomenon.”

Julio Ligorria Carballido, Guatemala’s ambassador to the United States, told The Tico Times later that the problem is not one of inadequate U.S. border enforcement.

“You cannot blame this crisis on any one thing. If you speak with ambassadors from the Northern Triangle countries or Mexico, everyone will tell you we all have a shared responsibility,” he said. “But everyone has a lot to gain by resolving this.”

Ligorria said that six weeks ago, Guatemala’s foreign minister, Luis Fernando Carrera Castro, became the first – and so far the only foreign minister – to visit the border during a trip to McAllen, Texas. He noted that of the nearly 58,000 unaccompanied minors who have found refuge in the U.S. since October, 12,000 are Guatemalans.

“We have to look at the violence in Central America, the hunger, misery, poverty and lack of education,” he said. “These are structural problems of our society that resulted 30 years ago from the Cold War. Help us to manage the crisis, but if you really want to solve the problem, you can invest in our countries. Promote real U.S. investments in Central America, and take advantage of the lower wages. And increase cooperation to solve narco-violence and our other social problems.”

Recommended: Fix the immigration crisis at its root