I live in a typical Costa Rican barrio. I define a barrio here in much the same way I define a village. Is there a soccer field? Is there a Catholic church? Is there a place to buy the basics and a place to get a beer? If the answer to all of those is yes, then you are in one or the other.

In my barrio, I live right around the corner from the soccer field. Sundays, there is usually a game, sometimes two or three, involving various nearby local squads. The excitement level is high as friends and family accompany the teams, and the sidelines are ringed with spectators. From my house, I always know when a goal has been scored. In all ways, this seems like the typical soccer pitch in the typical Costa Rican neighborhood.

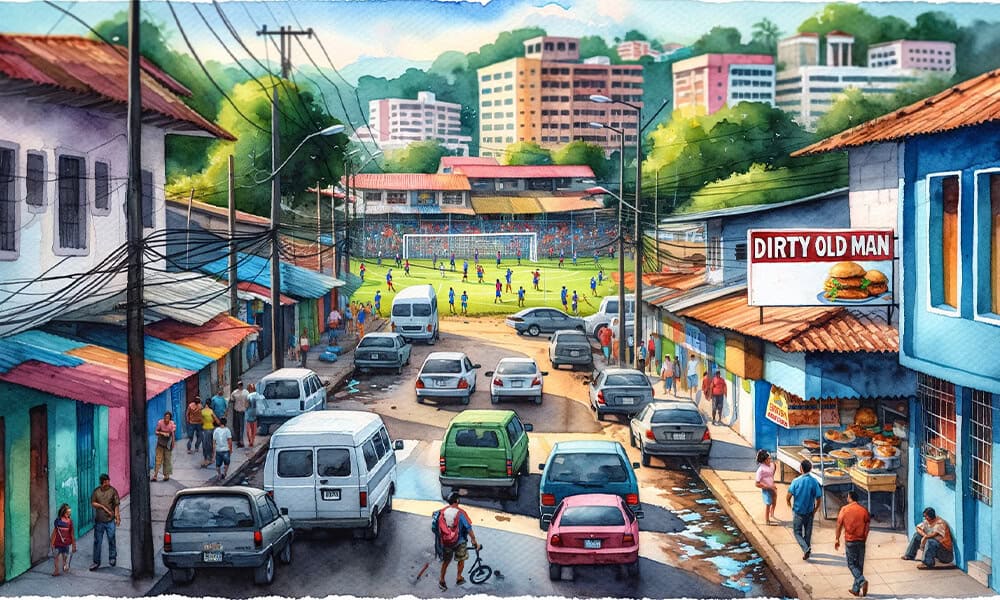

When organized games are not going on, it doubles as a massive playground, part exercise area, part family picnic, part soccer mejengas, part dog park. The main street of the barrio runs downhill for over a kilometer, ending at the edge of the city. It is a narrow street with car and bus traffic going both ways. Pedestrians walk a fine line between the vehicles and the open gutters. Recently, a man died when he parked his car with his driver’s side wheels in the gutter, and the car tipped over on him as he exited.

A heart with a halo above it was painted there afterward, signifying an accidental traffic-related death in the street. Businesses come and go here. Most are storefront operations, with the owner’s living quarters behind. The most successful is a small carry out only place that specializes in empanadas.

The name of the place is the Spanish slang for Dirty Old Man (though all the workers are young men). As often happens here, once this business appeared successful, another person opened a small place offering a similar menu a couple doors up. Then down the street, another person opened a small fried chicken outlet.

The ‘Dirty Old Man’ and the fried chicken place remain in business. One thing separates this barrio, and its soccer field, from the rest in this city– this is where Keylor Navas grew up. The soccer field is where he honed his game. You know the name if you follow soccer at all.

If you don’t follow soccer, Keylor Navas is by most measures, Costa Rica’s best ever player on both the local and international levels. He was one of the stars of the 2014 World Cup team that stunned and entertained fans worldwide by beating Uruguay, Italy and Greece on its way to a Top 8 finish. He starred for several years as the main goalie for powerhouse Real Madrid.

This is akin to being a star pitcher for the New York Yankees, or the point guard for the Los Angeles Lakers. When I first moved here, his grandparents’ house where he spent much of his youth was pointed out to me. It was a humble, sagging, wood frame structure, located on a corner of the main street.

Later it was razed and replaced by a sleek modern fenced in house of concrete and glass. A local taxi driver related to me that when Navas returned from his heroic World Cup performance, he made a much-anticipated arrival at the local soccer field– in a helicopter.

The taxista was unimpressed. To him it was a grandstanding move that showed how far he had strayed from his roots. I didn’t see it that way. Navas was taking time out of his busy schedule to return to the pitch where he got his start. Certainly, it was a day none of his young local fans would ever forget. That day was years ago.

If Keylor has been back to the barrio, he kept a low profile. He has been a resounding success, but the taxista’s reaction that time always stuck with me, because it reflected a feeling I have sensed from a lot of Ticos, that the humblest job is as significant as the most glamorous.

To this day, there are no statues or plaques commemorating that Keylor Navas once walked these streets and played on the local pitch. And at this writing, the expensive, modern house that replaced his grandparents’ humble casita sits unoccupied.