Getting immersed in the world of arts and culture, analyzing it as a means of philosophical enjoyment, and using his abilities in the art business is something that Klaus Steinmetz, has been doing for more than 25 years.

It all began when he was a high school student at the bilingual San Judas Tadeo High School (now known as the St. Jude School) and was inspired by of his teachers: Víctor Flury, a Peronist refugee who ended up as educator in his school and an important key figure in the Costa Rican cultural sector.

After this, Steinmetz graduated and was obliged by his father to study business management in order to continue with the family business, a hardware store. He began his business management studies at the University of Costa Rica (UCR), but later on transferred to the Fidelitas to finish.

However, eager to become a writer, Steinmetz left for Germany and ended up studying philosophy at the University of Tübingen. He did not finish the degree because of language barriers and moved on to the career of art history. He then had to move back to Costa Rica to help out his father with the family business, but continued his studies of art history at the UCR.

He also began writing about art for a national culture magazine, and then became an art critic for the Costa Rican daily La Nación. Steinmetz began buying his classmates’ artwork and saw the potential for a career as an art dealer, which grew organically as Steinmetz began traveling to Colombia and Mexico and bringing Latin American art to his gallery in Costa Rica, Klaus Steinmetz Contemporary.

He says that all of these achievements are part of a path full of coincidences.

“There’s a series of accidents that happened that you can see as accidents, coincidences, but really respond to a different plan that in the moment you didn’t pick up on. If you’d been prepared to take those paths or taking advantage of those opportunities, you wouldn’t have done so,” Steinmetz told The Tico Times.

Steinmetz settled his business in Brazil, Peru and Panama, and ended up as an art broker in Miami. After 18 years, he chose to close his gallery this month due to the prevailing economic difficulties that the country faces. Steinmetz, who has earned both national and international awards for his hard work and efforts to support cultural life, now continues with his private projects both inside and outside of Costa Rica.

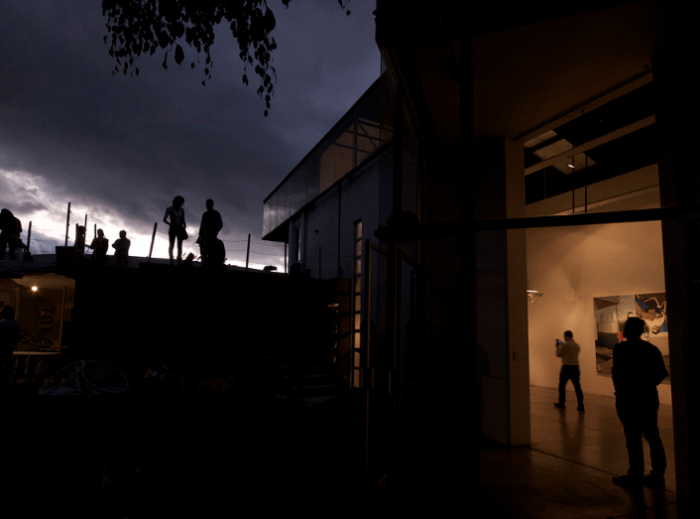

On a sunny day at Cueropapelytijera in Rohrmoser, in western San José, The Tico Times sat down and spoke with Steinmetz, 56, about his life and work. Excerpts follow.

How did you start integrating all of your artistic passions?

I don’t believe that it’s something that you have separately. You have an attitude towards life. I love people who are integrally cultured: you notice that they write, paint, and do photography because it’s an experiential way of feeling culture. I’ve never believed in the people who are painters or writers because they want to be famous. You can see they’re not true artists.

It doesn’t matter if you find someone whose paintings are horrible, or that they write terribly. It’s someone who needs it, who has that urgency in making culture; if they don’t, they get sick. I’m like that.

When did you notice that you couldn’t separate these things in your life?

It’s a daily attitude. All of a sudden you constantly feel the need to change schemes and routines. Generally, people who are not creative only feel comfortable and don’t suffer panic attacks if they keep themselves in the routines and schemes. Those are the people who go to work every day through the same route, who order their blouses and shirts by color, and have their houses perfectly ordered.

It’s great and important that these types of people exist in the world because they’re the ones who keep the world going. With us [creative types], the world would be a disaster.

I’m not like that. There’s a basic need of breaking the scheme. It could be called madness or whatever, but I insist it does not mean making a piece of art. It means… dancing at the beach alone with no one watching. It’s not thinking structurally, accepting a quota of irrationality in your daily life, which I think is very important. I noticed it when I got into the business part of art.

Within the political context of our country during the elections, how is it that there are two cultures in Costa Rica living in one territory?

I don’t believe they’re different. The moral topic was exploited in these elections, which is what explains them. If [former Vice President] Ana Helena [Chacón] hadn’t presented the consultation to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights about same-sex marriage, the [evangelical] National Restoration Party would have gotten three percent of the vote. I’m convinced about that.

Moral [issues] were positioned, and you can see that sometimes an erroneous interpretation of a tweet from the Education Minister is more scandalous than the structural problems of the country. It’s really ridiculous. Now if you want to pass a fiscal reform, you have to prohibit abortion. Costa Rica fell into that moral manipulation.

I’m not saying they’re not important topics, because they are. But the voters who voted for the family, who voted against abortion and same-sex marriage, are the ones who’ll face a dreadful hunger when the crisis bursts, which is happening, but it’s going slowly.

I do feel that on the topics of daily subsistence like paying the light, water, phone bills and bread, the country’s not polarized. I do think that the vast majority wants a change, but it has been confused about how to get to that change.

Is this current context of the country related to Costa Rica’s culture?

I’ve insisted that you cannot save on culture. At some point Costa Rica lost all of its taboos. The dishonesty taboo was lost, for example. Nowadays a public worker does not evaluate whether what he or she’s doing is moral. They do not evaluate if what they’re doing harms society.

For example, the Supreme Court of Justice says: OK, touch all of the pensions except ours. That’s immoral because what they care about is the legality. The idea of morality was replaced by legality.

[Immanuel] Kant said that in society, for a legal contract to exist, there must be a categorical imperative, which is what you have inside on a level of conscience and that impedes you from acting immorally. With the case of the Supreme Court of Justice, when did those values get lost? I really wouldn’t be able to say it with certainty, but it was a process, because you don’t lose that from night to morning.

The task on a cultural level would be to try to reinstate that notion of being social, the social conscience in the individual that he or she has to act as a community. It’s not happening currently. It’s the law of the jungle.

What has been imposed in Costa Rica is the doctrine of every man for himself. If I can threaten to paralyze the country through a strike in order to guarantee myself certain advantages that the rest of the population doesn’t have, then I’m acting on personal interests and in a myopic way, because you cannot milk a dead cow.

Why did you close your gallery after a broad trajectory and so many years?

The conditions. Many years ago, Jacobo [Carpio], Vicky [Pérez Ratton] and I began creating a small group of collectors with an international vision, but that did not prosper as it did in other places with the creation of Art Basel from Miami and all of the influence it has had. It prospered in Panama, Colombia, Guatemala, just to cite countries that are close and of our dimensions.

Also, the sales went down, and it was a very expensive operation. I won’t question the morality or legality, but Costa Rica does not compete comparatively. The salaries of keeping one employee in Costa Rica are impossible for the level of life in Costa Rica. It’s impossible for an art gallery that tries to survive in a very small market to have the basic quota of employees.

I also realized at some point that I was working for the government. I had to sweat to give the money to the government; I had nothing left. For many years I endured. I got sponsors. I told the people outside of Costa Rica that I did not sell art. I created events to get sponsors. I put on events in which I sold nothing or very little.

One day I simply said: no more. I can’t do it anymore. One thing is to want to do culture and another thing is damaging yourself for trying to make culture by forcing it.

Klaus Steinmetz Contemporary Gallery closed at the beginning of July after 18 years of working and 150 cultural events. In the past, Steinmetz was also president of the Board of Directors for the non-governmental organization for the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MADC) as well as secretary from the Board of Directors at the National Dance Company.

Steinmetz is currently working on his private projects and manages the Peninsula Fine Art Gallery at the Four Seasons in Guanacaste. For more information visit Klaus Steinmetz Contemporary’s website or Facebook page.

“Weekend Arts Spotlight” presents Sunday interviews with artists who are from, working in, or inspired by Costa Rica, ranging from writers and actors to dancers and musicians. Do you know of an artist we should consider, whether a long-time favorite or an up-and-comer? Email us at elang@ticotimes.net.