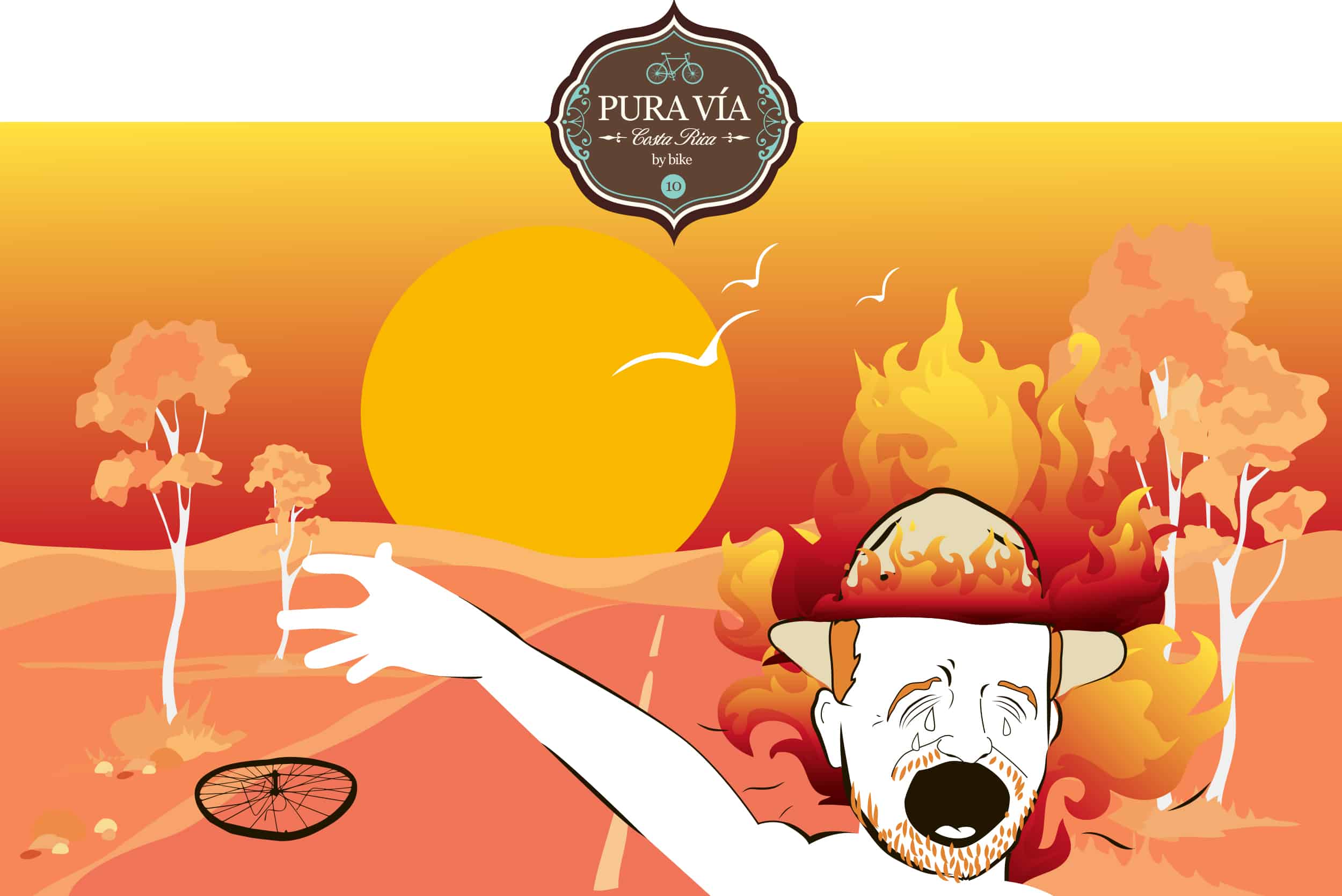

My bike started to wobble. My rear wheel juddered over the pavement. At first I ignored it. I didn’t want to accept the cruel truth: My rear tire was flat. When I dismounted, curses spat from my crusty lips. I looked up and down the road – the endless white concrete of the Inter-American Highway – and gritted my teeth as a bus howled by, blowing yet another veil of dust over my battered body. My muscles felt tight under the blazing Guanacaste sun. I was stuck in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by flat brown fields and wilting trees. There was no taxi service, no pedestrians, no nothing.

Halfway through my seventh day of biking, my tire had finally sprung a leak. I flipped the bike over and ripped the inner tube out of the wheel. After a half-hour of close examination, I found a staple stuck in the tire. It explained the puncture, but I couldn’t figure out why a staple had been lying on the highway. The hole was microscopic, which was why the leak had been so slow. I found a tiny dot and decided that that was the perforation, so I glued on a patch and pumped the tube with air.

But my patch didn’t work, and the tube deflated in seconds. I examined the bike again, feeling myself bake in the ferocious dry heat. I have long wanted to live in Liberia, the capital of Guanacaste, and whenever I divulge this dream, friends say: “It’s hot there, isn’t it?”

Indeed, it is hot. Guanacaste is the Texas of Costa Rica, a massive expanse of golden hills and ranches. Controlled fires burn year-round, sending columns of smoke into the air. Cows congregate in the pools of shade beneath solitary trees. Frightened by passersby, iguanas scuttle to the roadside.

I didn’t want to hitchhike, not on my penultimate day. But I knew I would have to remove my wheel and replace the whole innertube. Yet even then, there was a problem: I had forgotten that my folding bike didn’t have a quick-release system. I needed a wrench to remove the bolts that held my wheel to the bike frame. I had remembered everything – everything but a wrench.

As the heat beat down, I thought of the film “Lawrence of Arabia,” a childhood favorite. I remembered what T.E. Lawrence’s Bedouin guide had called the Arabian desert: “God’s Anvil.” Thirsty and sunburned and completely exposed to the sun, I felt a new appreciation for that phrase.

As luck would have it, there was a house nearby. When I knocked on the door, a woman came out. I didn’t know the Spanish word for wrench, so I said awkwardly, “Good afternoon! Do you have a thing I could use to fix my bike?”

To my great surprise, the woman smiled and said yes, and a moment later her husband appeared. Juan (not his real name) was a trim, middle-aged man with an airy voice. Their three sons scrambled outside, the oldest carrying a bouquet of tools.

“Thank you so much for helping me,” I said.

“Of course!” exclaimed Juan. “I’m a mechanic! It’s what I do!”

The serendipity bowled me over. Apropos to nothing, I had knocked on the door of a professional car mechanic. I am not the kind of person to describe events as “magical,” but this moment was: Juan’s eldest son proceeded to take the wheel apart, strip the tube from the tire, and insert my replacement tube. The surgery wasn’t complicated, but the boy giddily went to work, waving off any assistance. Juan crouched against the wall of his house, proudly watching his son’s handiwork.

“Have you ever been to Death Valley?” Juan asked in English.

“Uh, yes, actually. Have you?”

“I worked there for a while,” said Juan. “I used to work on cellphone towers. Have you ever been to Philadelphia?”

“Uh, yes?”

“I spent time in Philadelphia when I was a merchant marine,” Juan said.

Juan recollected his younger days in the U.S. as his son finished the repair. When he had screwed the wheel back into place, we used my pump to inflate the tire, and I took a test ride around their yard. The tire stayed firm. The 10-year-old boy was beaming.

“Would you like some mango?” asked Juan.

His wife emerged from the kitchen with a small plastic bowl. Inside, a mango lay sideways, but its color was golden brown. Juan explained that the mango had been covered in sugar and fried in a pan.

“It’s a dessert,” she said. “We’re making them for Easter dinner.”

Even if I wasn’t hungry, I couldn’t turn down such generosity. Each bite of the mango was a blast of fruity sweetness, and I promised myself that I would try to make the same thing at home. Their hospitality was humbling, but it also dawned on me how much of the past week I’d spent alone: Unlike bussing and backpacking – my usual modes of travel – bicycling is a solitary activity. Cyclists may physically engage with a country, but they still miss chances to interact. I had ridden 400 km in silence, humming to myself, focusing on the road, and only snapping out of my trance to admire a mountainous vista. A part of me was grateful to break down, to stop and taste the mango.

“Can I offer you something?” I said, groping my chain wallet.

“Please, no,” said Juan. “It’s Semana Santa. It’s our pleasure.”

I thanked them profusely, pedaled to the highway, and waved one final time before they disappeared beyond the trees.

I have always felt welcome in Liberia, that sleepy little hub in the heart of Guanacaste. The streets are wide and the pace is slow. Teenagers seem to ride their skateboards in the central plaza 24 hours a day. Locals are always smiling and telling me, “Pura vida.” Every chance I get, I stay at the Hotel Liberia. There’s nothing outstanding about this antique guesthouse, but I am always happy to return. Even the cold showers are refreshing.

I spent my final night walking Liberia’s streets. It was Easter Eve, and amateur fireworks exploded in the distance. A congregation gathered outside the church and listened to a sermon over the loudspeaker. The place felt so peaceful. As I stretched away my leg cramps, I realized how close I was to the end: Thirty more kilometers, and I would reach Playas del Coco. The journey felt both impossibly long and far too short. Yes, my lower body burned with overuse, but still I yearned for more time.

Robert Isenberg is a writer and photojournalist. He is the author of numerous books, plays and documentaries. Visit him at robertisenberg.net.