GUATEMALA CITY, Guatemala — Guatemala’s growing protest movement against government corruption continues unabated despite Vice President Roxana Baldetti’s decision to step down on May 8.

On Thursday, the Guatemalan legislature voted in as the new vice president Alejandro Maldonado, a Constitutional Court judge and career politician with a history of right-wing politics.

It’s been a month since the U.N.-supported International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) uncovered a massive customs fraud network known as “La Línea” that was allegedly led by Baldetti’s private secretary Juan Carlos Monzón. Since then, thousands of Guatemalans have demonstrated across the country on several different occasions, demanding the resignation of Baldetti and President Otto Pérez Molina, and an end to the graft and crookedness that has long characterized Guatemalan authority.

Students from four different universities have called for another peaceful march against corruption for this Saturday. In an unprecedented show of unity, middle- and upper-class students from the country’s top three private universities will take to the streets alongside students from the state-funded University of San Carlos under the slogan “Indifferent and silent never again.”

The demonstration will begin in front of the Guatemalan Supreme Court — a commonly-used protest gathering point, which on this occasion holds symbolic weight. One of the court’s judges was recently tainted by the scandal.

On May 8, the U.N. anti-impunity commission CICIG arrested three lawyers representing key defendants in the case and accused them of running a “Law Firm of Impunity” that bribed corrupt judges to make unjustified decisions favoring organized crime groups. Wiretap recordings show how the three lawyers bribed Judge Marta Josefina Sierra González de Stalling in exchange for her granting unguarded house arrest instead of prison for some of the defendants, and reduced bail.

According to investigators, two of the defendants paid Q250,000 ($32,000) each, while four others paid Q200,000 ($25,000) each. In light of the evidence, CICIG filed a request for the judge to be removed from the case and impeached.

The judge’s sister-in-law and president of the criminal chamber of Guatemala’s Supreme Court, Blanca Aida Stalling Dávila, was also mentioned in the recorded conversations.

“We are here, we haven’t abandoned you at all, you know that,” businessman Luis Mendizábal told one of the defendants in a conversation recorded by CICIG on April 16. “Blanca Stalling is behind all of this and they [the law firm], have very good connections, we’re working on that.”

Stalling insists that the names of the two judges were mixed up, and she agreed to cooperate with investigators in hopes of clearing her name.

Mendizábal — a controversial figure who was involved in a bizarre murder mystery in 2009 — is also accused of being part of “La Línea” and is currently on the run.

The new ‘Guatemalan Spring’

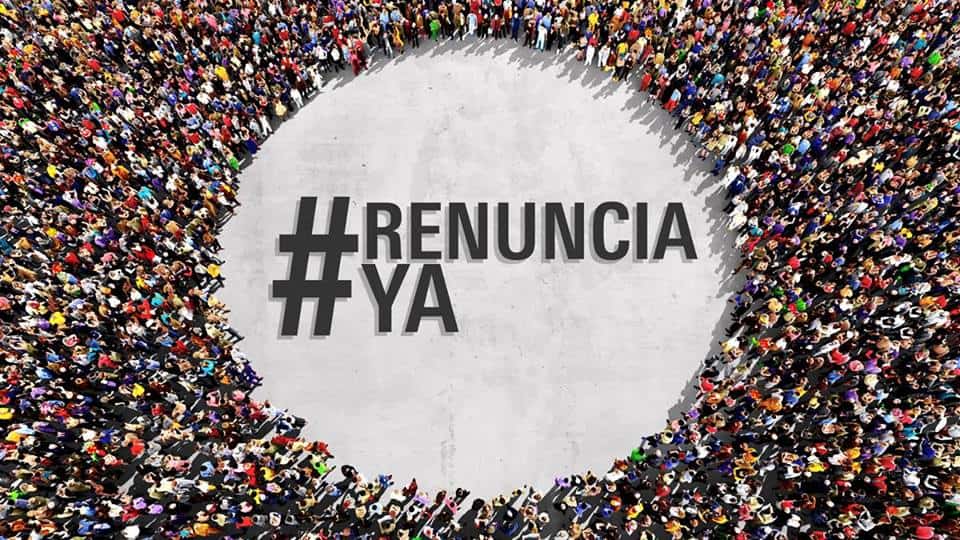

The fact that the current protests have been organized on Facebook and Twitter under the hashtag #RenunciaYa has led to comparisons between Guatemala’s peaceful demonstrations and the protests in Egypt’s Tahrir Square that brought down the Mubarak regime in 2011.

In a country where a recent history of repressive military rule has instilled a deep fear of political activism in many Guatemalans, observers have labeled the new youth-led citizen movement “a Guatemalan spring.”

The country has already lived through one spring — seven decades ago. In 1944, Guatemalans ousted dictator Jorge Ubico and elected a reform-minded professor, Juan José Arévalo, who, along with his successor, Jacobo Árbenz, instituted a series of progressive social, economic and political changes that lasted until Árbenz was forced to resign and abandon the country (in his underwear) in 1954.

Now, the sense of collective outrage that brought about that first spring seems to be back. As of Thursday evening, 29,000 people had made an online pledge to attend Saturday’s protest.

Most surprisingly, the recent demonstrations have joined together sectors of society that don’t normally mix — wealthy oligarchs and leftist artists; human rights activists and regular citizens. Many are voicing their frustration and discontent not only with the current administration but with the entire political class.

Still, four months before the country holds general elections, many Guatemalans feel disheartened by what they regard as a lack of options for change.

Manuel Baldizón, presidential candidate for the Democratic Freedom Revival (LIDER) party, is still leading the polls. A right-wing populist, Baldizón promises to introduce the death penalty and a regressive flat tax. The most recent poll, conducted by Prodatos and published by Guatemalan daily Prensa Libre on May 4, shows 32 percent of Guatemalans would vote for him.

He is closely followed by Sandra Torres, candidate for the center-left National Unity of Hope (UNE) party and former first lady to Álvaro Colom, with 31 percent of intended votes. Alejandro Sinibaldi, who defected from President Pérez’s Patriotic Party in the wake of the customs fraud scandal and has yet to choose another party, sits in third place with 23 percent of intended votes.

Although Baldizón is still in the lead, his popularity has stagnated, and on May 9, during a party rally held in the colonial city of Antigua, a scuffle broke out when protesters clashed with LIDER sympathizers.

Baldizón’s campaign slogan, “Le Toca” (“It’s his turn”), has been morphed by social media users into #NoTeTocaBaldizón (It’s not your turn Baldizón).

https://www.facebook.com/1404093059893636/videos/vb.1404093059893636/1434457753523833/?type=2&theater

A 2009 WikiLeaks diplomatic cable revealed Baldizón wooed members of Congress from the official UNE party by offering them $61,000 to switch allegiances. Another cable describes him as having “little substance to his politics.”

But perhaps the most damaging allegations are those contained in a 2011 report by Washington-based think tank Insight Crime claiming that Baldizón’s family made its fortune by trafficking archaeological artifacts in the northern department of Petén. Insight Crime also alleged that his party’s mayoral candidates in Petén were funded by drug cartels.

The accusations have led to widespread perception that Baldizón’s administration is just as likely to be tainted by corruption and ties to organized crime as that of Pérez.

Baldizón’s reputation has also suffered since he filed a lawsuit against Juan Luis Font, a respected journalist and director of Contrapoder magazine, after it revealed that the presidential candidate had plagiarized large sections of his 2014 book “Rompiendo Paradigmas” (“Breaking Paradigms”).

Paradoxically, the polls show 75 percent of Guatemalans have a favorable opinion of disgraced former president Alfonso Portillo, who returned to the country in February after serving a prison sentence in the U.S. for conspiring to use U.S. banks to launder $2.5 million in bribes from the Taiwanese government.

Despite his tainted past, Portillo enjoys considerable support among disenfranchised rural and urban Guatemalans due to the fact that he imposed price controls on basic foodstuffs, subsidized electricity rates for the poor, increased the minimum wage and challenged monopolies.

In contrast, under the Pérez administration, the chronically-underfunded public health care system hit an all time low, with three of the country’s major hospitals grinding to a standstill this year after they ran out of food and medical supplies. Pérez has also failed to deliver on his pledge to reduce crime rates, while a shortage of gasoline has prevented police agents from attending emergency calls.

Many of the homemade placards waved by demonstrators during the country’s recent wave of protests referenced the fact that while “La Línea” was allegedly pocketing Q2 million ($260,000) a week, the country’s hospitals, schools and police stations are broke.