When the guerrilla army of the Sandinista National Liberation Front, led by Daniel Ortega, took over Nicaragua in 1979, one of its first acts was to seize the assets of the country’s business oligarchs.

One target was the Pellas family, prominent since Francisco Alfredo Pellas, who arrived in Nicaragua from Italy in 1875, got rich by producing sugar and operating steamships on Lake Nicaragua. The FSLN seized the family’s real estate and its bank, Banco America, and later took over its sugar mill, the biggest business in the country.

The Pellases commuted between Nicaragua and Miami during the eight-year Contra war, which pitted supporters of the old regime against Ortega’s army. That conflict ended in 1987 in an agreement brokered by Costa Rican President Óscar Arias. Carlos Pellas, Francisco’s great-grandson, then 34, started rebuilding the family fortune — a process that was violently interrupted in 1989, when Carlos and his wife, Vivian, were almost killed in a plane crash.

Between surgeries, Pellas worked quietly to recover his sugar mill, which he did in 1992, when President Violeta Chamorro, a distant relative, returned expropriated properties to their original owners. Pellas helped start a new bank, BAC-Credomatic, which, by 2005, was one of the largest financial institutions in Central America. Its sale to General Electric was completed between 2005 and 2010 for about $1.7 billion.

Today, privately held Grupo Pellas runs four sugar mills, produces ethanol and provides the raw material for Pellas’ Flor de Caña brand of rum. The group controls more than 20 companies, with stakes in media, distribution, insurance, citrus, health care and auto dealerships. It boasts $1.5 billion in annual sales — equal to 13 percent of Nicaragua’s gross domestic product — and employs some 18,000 people. Carlos, 61, the major shareholder, is Nicaragua’s first billionaire, with an estimated fortune of $1.1 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

That figure was derived by analyzing the value of Pellas’ real estate assets, dividends received from his closely held companies and the value of transactions including the sale of BAC-Credomatic. The valuation of Grupo Pellas as a whole is based on comparisons with corporate peers, using estimated enterprise value-to-Ebitda and price-earnings multiples.

Pellas has demonstrated consummate skill at steering the family business through Nicaragua’s political swings during the past 20 years — as his forebears did before him, says Francisco Mayorga, a Yale University-educated economist who was central bank governor in the 1990s under Chamorro.

“The Pellas family has managed to survive and increase its fortune in volatile and often adverse conditions,” Mayorga says. “They have faced every possible political environment: American interventions, civil wars, revolutions.”

Pellas has built his wealth amid some of the worst poverty in the Americas. Nicaragua is the second-poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere, after Haiti, with a per capita GDP of $4,500, according to data compiled by the Central Intelligence Agency. Some 65 percent of the population works outside the mainstream economy, including vendors selling pirated DVDs, Coca-Cola in plastic bags and homemade cheese in the streets of Managua, the capital.

While social welfare programs have chipped away at the privation, most rural Nicaraguans still live in poverty, many inhabiting homes with dirt floors and no indoor plumbing. The destitution has been heightened this year by one of the worst droughts in decades, which has ravaged crops and cattle herds and prompted the government to recommend that people raise and eat protein-rich iguanas to stave off hunger.

Pellas says he does what he can in his family’s business to alleviate hardship. His sugar and rum companies provide free health care to workers, and he runs a school that offers 500 scholarships a year to his employees and their children.

The billionaire says local development and job training are also priorities at his pet project: a 676-hectare (1,670-acre) luxury resort, now in its second phase of construction, called Mukul, in a remote cove on the country’s Pacific Coast. Mukul — which means hidden in Maya — provides English and hospitality classes for employees, plus health care, potable water and a soccer academy for the local community. For vacationers, Mukul features suites at $550 a night, spas, nature walks and a golf course by David McLay Kidd, who designed the Castle Course at St. Andrews in Scotland.

“People still think Nicaragua lives at war,” Pellas says as he smokes a cigar in his personal thatched-roof hut with infinity pool at Mukul. “We’re trying to create a spark to change that image. And we want the wealth here to permeate into the rest of the region.”

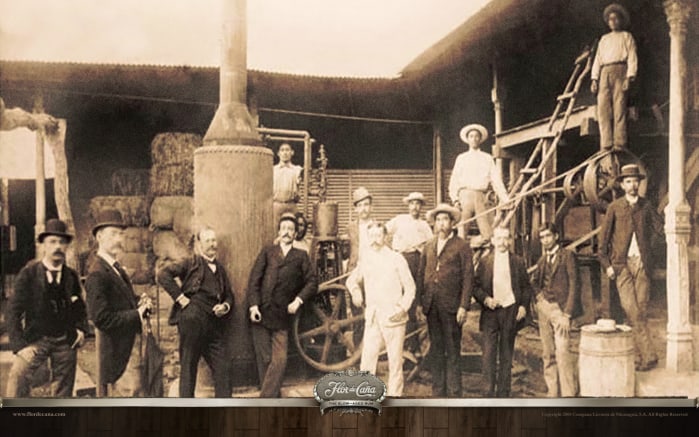

Mukul is southwest of Granada, on the shores of Lake Nicaragua, where Pellas was born in 1953. It was in Granada that Pellas’ great-grandfather launched Nicaragua Steamship Navigation Co. and, in 1890, Nicaragua Sugar Estates Ltd. While the sugar business flourished, the navigation company lost momentum as the U.S. chose Panama over Nicaragua for an interoceanic canal — an idea that Ortega has revived with backing from a Chinese investor.

Related: Nicaragua canal survey off to rocky start marked by fear and mistrust

Pellas, who has a Master of Business Administration degree from Stanford University, built his business empire while enduring repeated skin graft operations to treat burns suffered in the 1989 plane crash. The bearded businessman lost parts of four fingers in the accident and uses hand prosthetics.

Pellas says he has a good relationship with Ortega, 70, who, after losing the presidency to Chamorro in 1990, regained power in a 2006 vote. A vow not to confiscate property won Ortega credibility with the country’s biggest business council, Cosep, Pellas says. Ortega can run in 2016 for his third consecutive five-year term; he had the legislature amend the constitution to allow for it. Pellas says Ortega strongly backs his Mukul resort and other efforts to increase tourism.

See also: 35 years after Somoza’s overthrow, not much for Nicaragua to celebrate

Yuri Kasahara, researcher at the Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research, says Pellas warmed to Ortega after the Sandinista party boss helped block a 2002 bill from allies of former President Arnoldo Alemán that would have repealed tariffs on imported sugar. The proposal was part of Alemán’s attack on the business backers of the government that was prosecuting him on corruption charges, and Sandinista lawmakers killed it after Pellas appealed to Ortega for help, says Kasahara, co-author of the book “Business Groups and Transnational Capitalism in Central America.”

Ortega’s cultivation of rich businessmen such as Pellas is proof that he’s as power hungry as any of his predecessors, says Dora María Téllez, who was a leader of the movement that overthrew dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle in 1978.

“It’s the same model that Somoza used,” says Tellez, who served as Ortega’s health minister in the 1980s and left the FSLN in 1995. “I’ll let you have your money, and you let me have my politics. It’s an alliance between the old oligarchy and the new oligarchy of Orteguismo.”

Téllez is now a member of the Sandinista Renovation Movement, an opposition party.

Pellas has taken the sugar business in directions his ancestors never dreamed of. His factories produce ethanol and bagasse, the residue from the sugar cane harvest that’s converted into a biofuel, among other products. In addition, Pellas ships Flor de Caña rum to 40 countries.

“Pellas knows the sugar business isn’t just about producing sugar cane anymore,” says Julio Herrera, president of Guatemala City-based Pantaleon Group, which owns the largest sugar mill in Guatemala and the second biggest in Nicaragua. “His rum enterprise is an excellent business.”

Growing sugar cane has turned into a deadly business. Thousands of sugar cane workers across Central America have fallen ill with kidney disease in the past decade. Local records show more than 700 men have died since 2002 in Chichigalpa, the town where Pellas’ biggest business is based. In January, former sugar cane cutters staged a protest near Pellas’ San Antonio mill, demanding better medical treatment. Police gunfire killed a 48-year-old former fieldworker and wounded a 14-year- old boy.

After years of investigation, medical researchers haven’t pinned down a cause of the kidney disease. Pan American Health Organization researchers say heat stress with dehydration, excessive intake of high-sugar drinks and exposure to pesticides are possible causes.

Pellas began sending mobile clinics into cane fields last year to monitor workers, who can also get care at a company hospital.

“For us, it would be a miracle to find a solution,” Pellas says. “It’s very painful; the world needs to pay attention to it.”

These days, Pellas says he spends about 15 percent of his time supervising the completion of his southern Nicaragua resort. Unlike the sugar mill passed down through generations and shared with family members, Pellas is building the resort with his own capital. He says Mukul and vacation meccas like it, by taking advantage of Nicaragua’s natural beauty, offer one way to alleviate the country’s poverty.

“Money comes and goes,” Pellas says, as a servant at Mukul prepares him a cocktail. “This is more of a legacy project. I want them to say Carlos Pellas turned Nicaragua into a tourist destination.”

Adapted from Bloomberg Markets magazine.

© 2014, Bloomberg News