Costa Rica’s Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGAC) continues to enforce a ban on nighttime operations at most aerodromes, pointing to reports of activities that fall outside established rules. The policy, in place since early October 2025, has drawn sharp criticism from the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS), which says it hinders emergency air transfers and endangers lives.

The DGAC issued two aeronautical information circulars on October 9, 2025, that redefine night operations. These require flights under instrument rules between sunset and sunrise and bar takeoffs and landings at uncontrolled sites after dark. Operations now limit to the international airports Juan Santamaría in Alajuela and Daniel Oduber in Liberia, plus Tobías Bolaños in Pavas during its set hours.

The agency describes the move as an enforcement of current safety standards, aimed at protecting crews, passengers, and ground personnel based on technical and legal grounds.

Officials at the DGAC base their stance on received complaints about operations not aligning with regulations. They frame the restrictions not as a outright prohibition but as equal conditions for all flights, including medical ones. Despite calls for change, the agency holds that the measures address safety gaps at sites without full night capabilities.

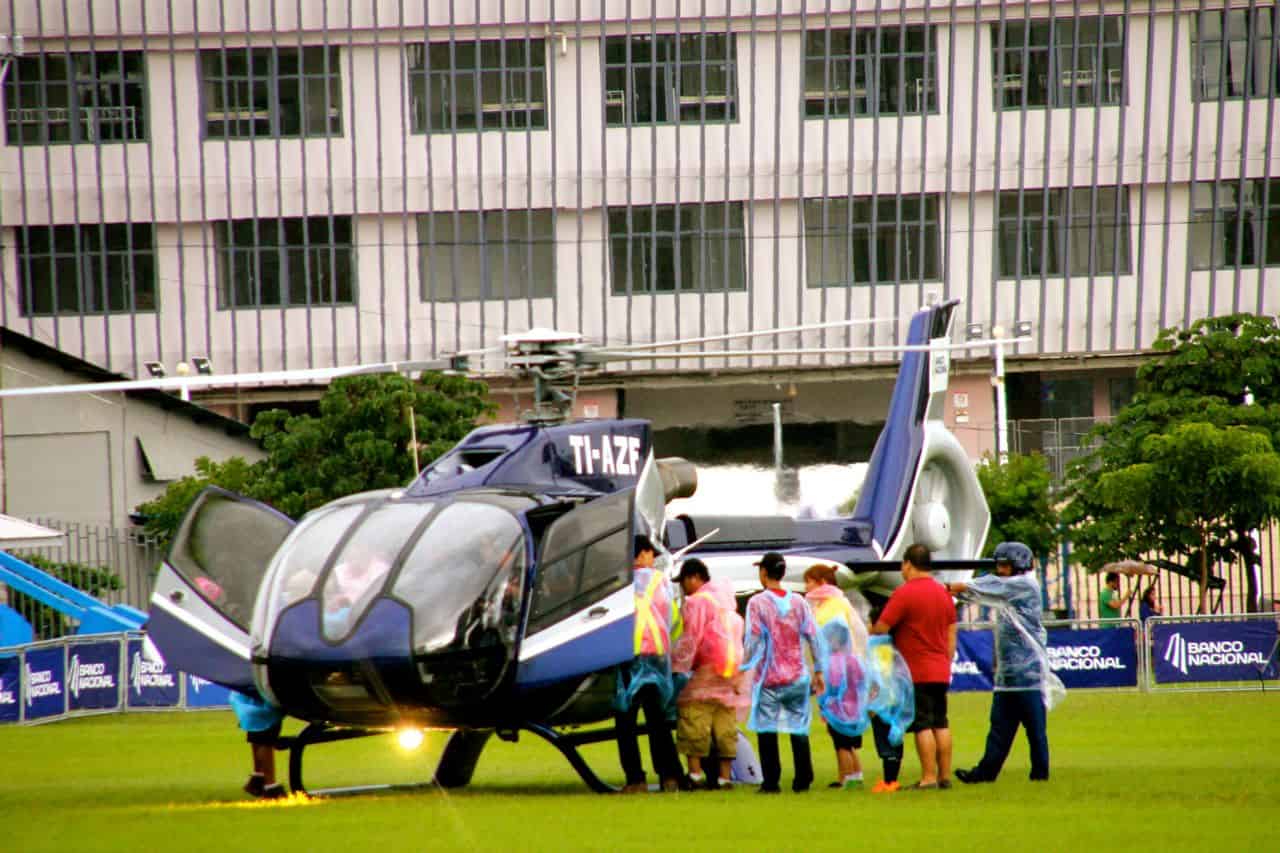

The CCSS, responsible for coordinating patient transfers, reports direct hits to care. The fund handles between 200 and 300 air evacuations each year, many from remote spots like the Caribbean coast or southern regions such as Coto 47 and Palmar Sur. Emergencies often arise outside daylight, making air the fastest option over rough roads or bad weather. With the ban, teams turn to ground ambulances, which can add hours to trips and raise risks of worsening conditions.

Hospital directors highlight the strain. At Hospital Enrique Baltodano in Liberia, staff note limits on moving severe cases, forcing land routes with backup plans. The Hospital Nacional de Niños in San José sees delays in treating children, disrupting team-based care. In Ciudad Neily, geography and traffic compound issues, heightening accident chances and tying up resources.

Specific cases underscore the problem. Since September 2025, six night transfer requests went unmet: four from Liberia’s hospital on September 7, 10, 28, and October 18, plus two from San Vito and Ciudad Neily on November 26. One incident involved a 7-year-old girl with a brain bleed who waited 14 hours for a flight from Liberia to San José. Airports closed due to clouds or hours, and she reached care in poor shape, later passing away.

Air operators add to the outcry. One firm logged 122 night ambulance flights over 18 months before the ban, part of 377 total. They report no accidents in such operations over the last 18 years and just one minor event in three decades—a runway animal strike. Pilots question who bears blame for lost lives, arguing the ban overlooks proven safe practices in critical zones.

The CCSS sought details from DGAC Director Marcos Castillo on September 17, 2025, covering flight ops, infrastructure, and approved sites. After no reply, they followed up November 7, stressing patient needs. On December 2, the DGAC noted internal reviews with legal and airport units, promising a future statement. As of mid-January 2026, no resolution has come.

Exemptions exist for the Aerial Surveillance Service, but it lacks ready aircraft for medical runs. Health leaders push for tweaks to allow emergency flights while meeting safety. For now, the CCSS adapts with ground options, though directors warn of ongoing threats to timely treatment.