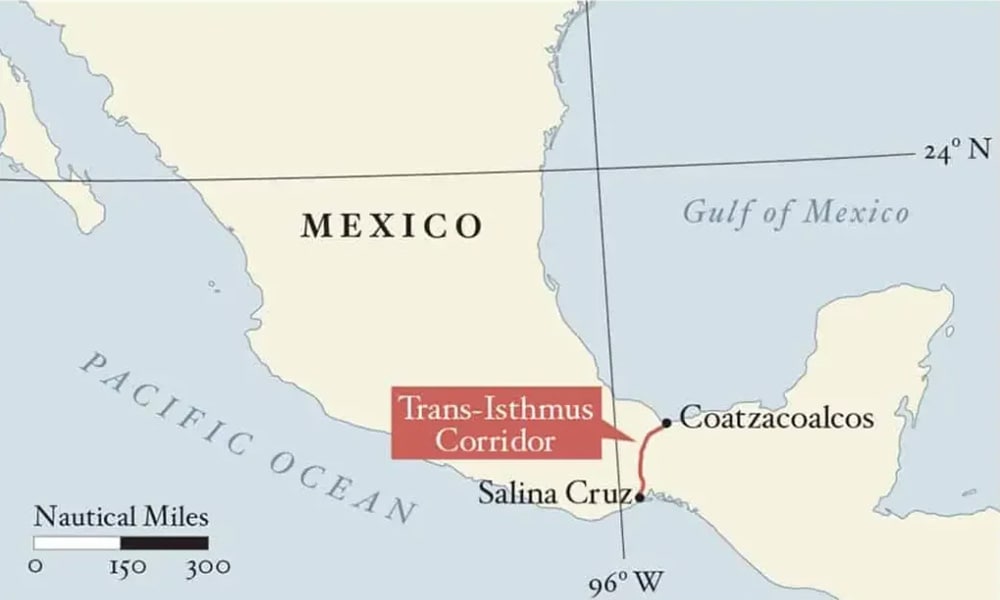

In the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a narrow portion of Mexican territory where 300 kilometers separate the Pacific from the Atlantic, an inter-oceanic corridor is being built as an alternative to the Panama Canal, which generates economic expectations, but also controversy.

The project, envisioned by the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés in the 16th century and pursued by Mexico for almost a century, is being developed in a region of numerous ancient indigenous peoples and extensive cultural wealth.

The work, which promises to complement the Panama Canal, rides on the popularity of the Mexican president, the leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador, whose government has invested $2.85 billion in freight and tourist trains to connect two revamped ports.

The corridor could add between 3 and 5 percentage points to Mexico’s GDP, according to the Executive. Opinions are divided between those who hope it will attract investment and boost consumption and those who fear it will facilitate the activity of organized crime, in addition to generating serious social and environmental impact.

“It’s a project that is magnificent!” says Angélica González, a 42-year-old artisan in Ciudad Ixtepec (Oaxaca, south), one of the stops on the train that connects the ports of Salina Cruz, on the Pacific, with Coatzacoalcos, on the Atlantic coast (Veracruz, east).

González was five years old when she last traveled on the passenger train, which later disappeared leaving only the freight train active.

She is excited to sell traditional garments that she knits with crochet hooks to future tourists. In September, López Obrador celebrated the return of passenger trains to the area, traveling by rail amid cheers from residents.

The business

Although tourism arouses expectations, the business is logistical and commercial. The Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (CIIT) expects to mobilize 300,000 containers per year in 2028, according to official data, and will increase to 1.4 million – an average of about 33 million tons of cargo, according to estimates – when it reaches full operational capacity in 2033.

In 2022 the Panama Canal, severely affected then by a drought, saw 63.2 million tons of cargo in containers cross through, according to its administration. It is estimated to move almost 3% of world trade, according to the same source.

Navy Captain Adiel Estrada, CIIT’s operational coordinator – which will be administered by the Mexican Navy – argued that the “backbone of the corridor” is that “it complements the Panama Canal.”

With the bidding of the corridor’s first five industrial parks, the government hopes to attract $7 billion in investment.

Monumental work

The expansion of the port of Salina Cruz is monumental. Its new jetty, which has already gained 1,000 meters from the sea and will extend up to 1,600 meters, requires 5.5 million tons of stone.

In Latin America “there is no other breakwater with this depth of 25 meters (…), it is a megaproject,” says Iván Santana, a naval engineer. The works, which began in 2020, generate 800 direct jobs and 2,400 indirect jobs, according to Estrada, boosting a region historically hit by poverty.

The population “sees the corridor with great encouragement” and its promise of prosperity, recognizes Rafael Mayoral, an activist from Salina Cruz. But he warns that this “does not erase” its environmental and social impact. Southern Mexico is the gateway for thousands of irregular migrants, whose exodus attracts cartels dedicated to human trafficking and extortion.

Ciudad Hidalgo, on the border with Guatemala where undocumented people arrive, will connect to the CIIT with the train that will reach Ixtepec. Another branch will link it to the tourist Mayan Train, also López Obrador’s work, marking new migratory routes.

Concern

Juana Ramírez, an activist from UCIZONI – a regional indigenous organization – sees the project as an imposition. “How will the isthmus end up? Polluted, with few animal and plant species and increasing violence,” predicts this indigenous Mixe woman, from the municipality of San Juan Guichicovi.

UCIZONI argues that the route violated international standards on consultation with indigenous peoples, presented flawed environmental studies, and has displaced native communities.

The activist claims that members of the Navy “repress and harass,” to the point that she was criminally denounced by the government along with 15 colleagues for “attacks on communications routes,” after a protest in April.

“It is a clear example of criminalization,” says Ramírez, who claims that if convicted, she would be fined $1.6 million. It was unable to corroborate such a sanction with authorities.

The woman also believes that with the work came “organized crime.” In addition, interviewed activists agree on an increase in land price speculation and the violent dispossession of properties in Salina Cruz and other municipalities, by mafias.

In July, the NGO Mexican Center for Environmental Law (CEMDA) reported 21 cases of intimidation, 11 physical violence and three homicides against territorial defenders between October 2022 and July 2023, all linked to the CIIT. Most of the victims were indigenous.