A proposed Mayan tourist train in Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula has divided residents in one of the country’s poorest regions, known for its indigenous uprisings.

“The train will no longer come through here,” rejoiced Guadalupe Caceres, 64, at news that the original route was being modified and would no longer pass through her home.

“We’ve lost, goodbye modernity,” responded locksmith Ruben Angulo, 49, who was hoping to be rehoused but still has his eyes on one of the half-million jobs the government has promised.

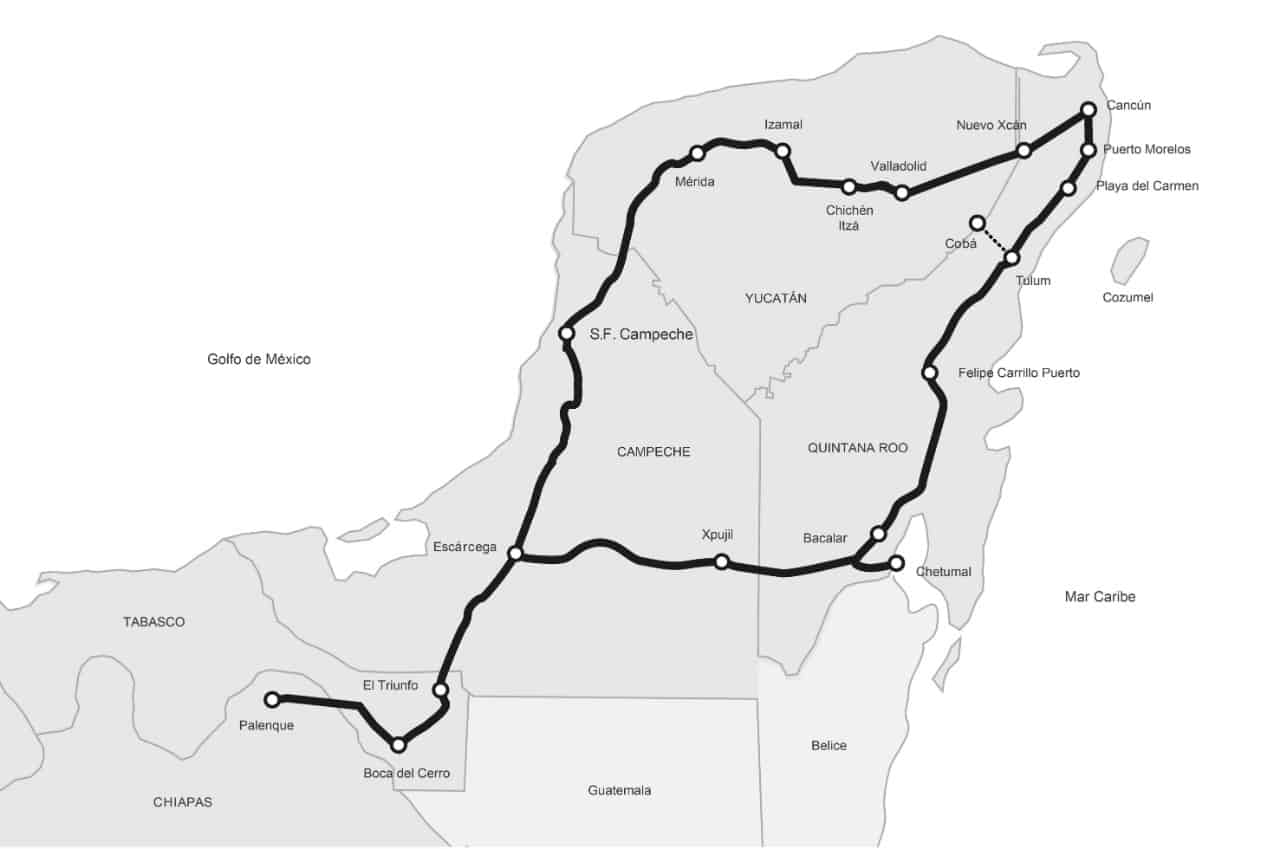

The mega works that will cover a 1,500-kilometer loop around the Yucatan peninsula was the signature proposal of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in 2019 to serve the popular tourist hub that includes seaside resorts Cancun and Tulum, as well as the Mayan archeological ruins of Chitzen Itza and Palenque.

“Yes, there will be (modernity), but not at the expense of my house,” said Caceres.

She took her objection to the courts and the train will no longer pass through the center of Campeche, a fortified colonial town where one of the 15 Mayan Train stations will be located, but will now remain on the outskirts

Lopez Obrador described the $10 billion train project — one of the biggest in Latin America — as “an act of justice” for the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatan and Quintana Roo.

Poverty in the region of 13 million people is over 50 percent, and reaches 75 percent in Chiapas. Public transport in the region is poor and some of the best sites to visit are far from the main cities.

National security

Many in the region reject the left-wing nationalist president’s claims the train will improve their lives.

The project’s detractors include environmentalists, indigenous people, government opponents and even the EZLN former guerrilla movement.

The project faces 25 legal challenges accusing it of violating environmental and housing rights. “We twisted the government’s arm,” said Caceres triumphantly.

Mexico’s center for environmental rights, which launched one of the legal challenges, highlighted the cutting down of trees in protected areas and the fragmentation of ecosystems that could turn them into “biologically degraded and inhospitable” places.

The challenge also pointed to the potential effects on water bodies, animal species in danger of extinction and mangroves.

Some 200 kilometers from Campeche lies another train station in Candelaria, close to the border with Guatemala. In a poor area without running water, 500 farmers have held a contractor’s excavator hostage since September, demanding compensation for the project cutting their village in two.

“Until this problem is resolved, we won’t let the works begin,” said Erendira Ocana, 30, from under a huge mahogany tree. A 227 kilometer long section — the first of seven — is due to pass through this point and is supposed to be operational in 2023.

Although the train does not pass through San Cristobal de las Casas, the Chiapas fiefdom of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), the former guerrillas have been active in opposing the project in the courts.

Faced with these challenges, Lopez Obrador declared his mega-projects a “national security” issue in November so that his opponents “could not prevent them.” The army has been enlisted to build tracks while Franco-Canadian firm Alston-Bombardier has been contracted to make 42 trains.

Potential disaster

According to Fonatur, the body tasked with delivering the project, it has the support of the majority of local residents.

In an attempt to appease environmentalists, Fonatur said it would extend Mexico’s largest tropical forest reserve, Calakmul, by 730,000 hectares to 1.2 million hectares.

Authorities have also announced plans to protect Mexico’s heritage in the face of a wave of tourists. Thousands of remains have been found during excavations.

Cancun and Tulum already attract 12 million tourists a year, although the tourist industry is controlled by major hotel chains. With an estimated 31 million visits in 2021, tourism will account for almost eight percent of Mexico’s GDP.

The train will “reconfigure the Yucatan peninsular and its repercussions will be long-term … it could go quite well or be disastrous,” warned Etienne von Bertrab, a professor of political ecology at University College London.

In Pixoyal, near Campeche, Guadalupe Perez feels like she has won the lottery and cannot wait for the train to arrive.

She is due to be moved to one of the new houses the government is providing for hundreds of families. Perez also sold food to the construction workers building the new homes.

“I wanted to set up a business selling food. I never gave up,” she said from what will be her new kitchen.

by Alexander MARTINEZ