A military patrol went into a school. The soldiers called 100 of the 315 students present by name and murdered them. All the students were from the Hutu tribe, in Burundi, 1972.

At the same time, Hutu soldiers in the army were called in by their superiors, all from the Tutsi tribe, to be similarly executed. The massacre continued in a systematic way in all the universities, churches, schools, institutes and farms nationwide.

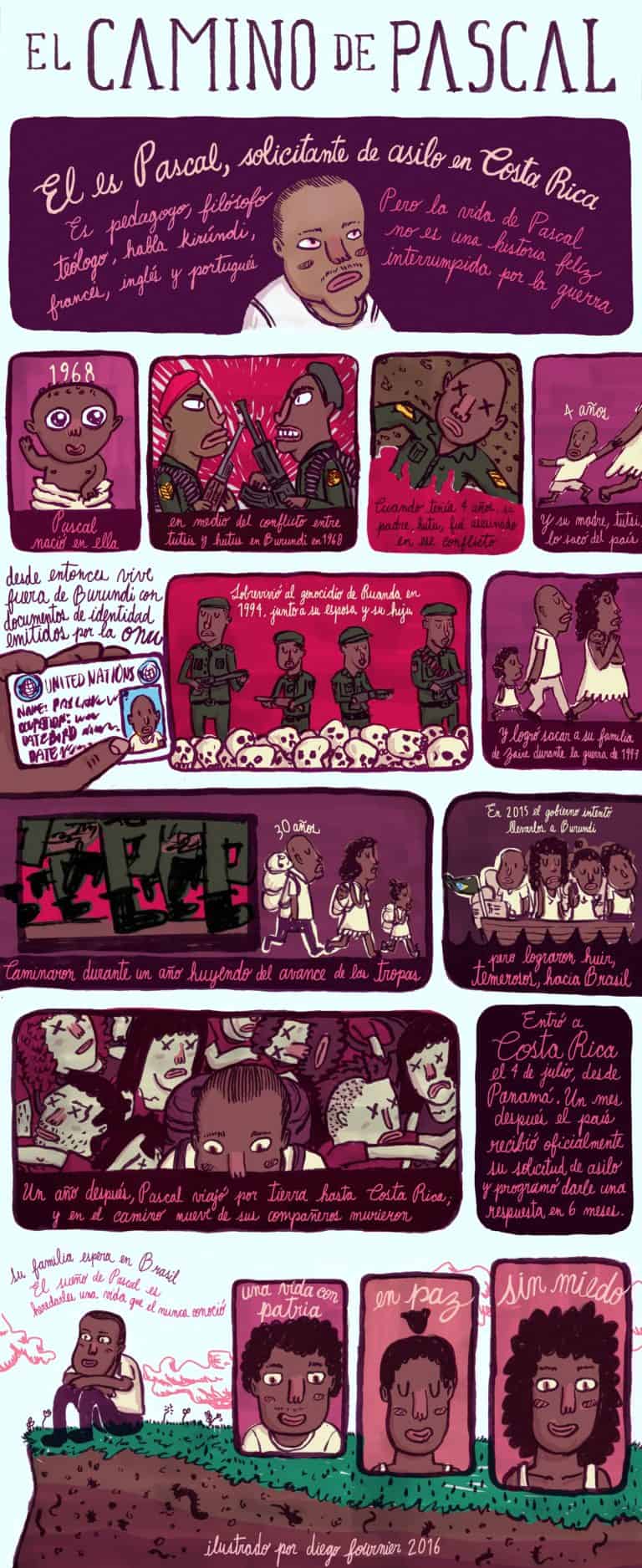

Pascal was four years old. His father was Hutu, his mother Tutsi. Before they could flee, his father was murdered and his mother saved Pascal’s life by casting him out, forever and with all her might, into statelessness.

Like Pascal, 10 million people all around the world do not belong to any country, nor carry documentation of their origins; that is, they do not legally exist.

Pascal arrived in Costa Rica one July 4th, nearly five decades later, covered with the dust of the road, bearing the scratches from his close encounters with death in wars, genocides and escapes. He came tired, hurt and alone.

Pascal’s flight

At the age of four, Pascal reached Zaire (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). He stayed there until the age of 18, when he went to Rwanda to study education. There, he met his wife, who was also of Burundi descent but was born in exile. They had their first daughter.

In 1994, Rwanda was the protagonist and victim of one of the cruelest episodes of the 20th century, known officially as the Genocide of Rwanda, the deadly persecution of the Tutsi people that culminated in the deaths of at least 800,000. Pascal, his wife and his baby managed to survive by escaping to Zaire, along with two million others.

There, in his third refugee camp, Pascal and his wife had their second child. Very soon, terror caught up with them again. An international military offensive led by the governments of Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda invaded Zaire, unleashing the First Congo War. In 1997 the invaders reached the capital and took over the government.

The family fled, as it had done before, but this time their flight lasted for an entire year, on foot. Eventually, they crossed Lake Tanganika and reached Zambia. However, will fearful family preferred to keep on traveling and get as far away as possible. That’s how they reached Namibia in 1998, where they lived for the next 17 years, in another camp, still refugees.

In 2015, thanks to the initiative of the new government of Burundi to recover the Burundi people scattered across the continent, the refugee camps were closed and the family had no option but to “return” to an unknown land they no longer thought of as theirs.

Feeling completely foreign to the Burundi of today and of yesterday, they decided to flee the uncertainty of central and southern Africa for good. They flew to Brazil with a plan to travel north.

Initially, the family obtained a temporary three-month permit, but one year later their luck did not hold out. That was when Pascal decided to travel only as far as Costa Rica – sometimes by bus, sometimes on foot.

First, he reached the Colombian border and crossed it, venturing into the mountains of the Darien Gap, where he joined a group of people planning to cross the area to enter Panama.

The group set off guided by a series of coyotes who charged them between $20-30 each per day to help them through the mountains. What’s more, as part of the group rules, all had to give up their passports to be destroyed.

As the days passed and the mountain became ever crueler, the migrants started leaving their belongings by the wayside; every gram of weight hurt. Then it started raining. The ground turned into sludge and the rivers into killers.

Even the trees and bushes joined in the cruelty, and soon there were more wounded than healthy. The group that arrived in Panama had been undone: nine of them had died on the way. Pascal had survived another test.

In Costa Rica

His arrival in Costa Rica coincided with that of thousands of African and Caribbean migrants hoping to reach the U.S. border and request asylum in that country.

During Pascal’s first weeks in Costa Rica, without understanding the language or how to begin the process of integration, the group of migrants grew rapidly.

Hunger, thirst, sun, rain, incomprehension, medical needs and the frustrations of thousands began to generate a heavy mood that mixed with the heat of Costa Rica’s Southern Zone and, later, of the northern canton of La Cruz.

As a response to the chaos, the Ministry of Governance and Police mobilized a team of volunteer interpreters to create an open line of communication with the foreigners. Meanwhile, the migrants organized themselves and elected a board of representatives that would direct the voice of the community with greater strength.

Pascal Hakizimana was designated as the contact with the Costa Rican government. Initially, he was in charge of explaining the basic needs of the group of migrants to officials from Costa Rican Immigration (DGME), the International Organization for Migration (IMO), the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the Red Cross, and anyone else he was asked to speak with as a representative.

Once he had assured some small victories for his group, Pascal decided to tell the Costa Rican authorities about his desire to stay in the country, and he officially sought refugee status.

His request was accepted by the Government of Costa Rica on August 8th, four weeks after his arrival. The process then changed. He didn’t speak for everyone; he spoke for himself.

His request got the attention of the UNHCR offices in San Jose, which called him in to document his case; Immigration referred him to the Association of International Consultants and Advisors (ACAI) to direct his legal case. In launching this process, Pascal must now face a bureaucratic system that asks him to wait, day after day.

Once he was settled in San José, he began the long process of integration. First up: finding a Pentecostal church, a Christian denomination to which he had belonged since his infancy. He located one in eastern San José and attends every Sunday service faithfully, even though virtually no members speak English, French, Portuguese or Kirundi, and Pascal is just beginning to learn Spanish.

Even so, a family that attends the church allows Pascal to stay in their house so he can have some company as he waits for the government’s response.

Authorities have already given Pascal a temporary work permit, but after two months of searching and despite his experience as a teacher and educational administrator, Pascal still can’t find work.

He must wait up to 10 months for the final resolution of his request. If it’s approved, Pascal and his family will join approximately 4,000 people who live in Costa Rica as refugees, according to the UNHCR.

Along with Pascal, 2,673 people requested refugee status in Costa Rica between January and August 2016. The UNHCR estimates that right now, the population of people with refugee status or waiting for resolution of a status request ranges from 6,000 to 7,000.

These figures were provided by Ana Laura Méndez during a visit to Contexto.

In Costa Rica, the policy for accepting migrants under refugee status is based on the General Immigration Law (Nº 8764 de 2009) and the Regulations on Refugees (Decree Nº 36831-G, 2011).

Until 2016, Costa Rica did not have an official procedure for declaring a person to be stateless. Until this year, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs could only declare people to be refugees.

With the new Decree Nº 39620, issued on April 7th, 2016, the “Regulation for Declaring the Condition of a Stateless Person” assigns that responsibility to the ministry.

What’s next?

While this group of African and Caribbean migrants did not seek to stay in Costa Rica, circumstances have meant that they have stayed longer than planned, and some are even starting to consider making this country their home for the rest of their lives.

After having been a refugee or awaiting refugee status the country then called Zaire, Rwanda, Namibia and Brazil, without having been fully accepted as a citizen, Pascal hopes that Costa Rica will let him take a seat and breathe easy.

If he manages to obtain an identity card as a naturalized Costa Rican, it would be the first nationality he has been assigned in his entire life. At almost 50 years old, Pascal has never been from anywhere.

“None of those places allowed us to become citizens. They received us refugees, nothing more, without any status. And when I watch my children grow up without a homeland, like me, it hurts. If we continue like this, one day I will have grandchildren – and they, too, will be like me.”

His family waits in Brazil, avoiding the dangerous passage during which their father and husband watched nine migrants just like them meet their deaths.

Pascal awaits and longs for his family; and his family, in the meantime, survives. Once in a while his children send him a song on WhatsApp from Brazil. They miss him, but understand the separation.

“I have to fight for a place where I can become a citizen so I can change my family’s situation, so that we belong somewhere. Soon I’ll be 50 – 50! – and I have never been a citizen.”

The family of four wait with the patience they have cultivated all their lives. They know that sometime, someday, somewhere in an office in Costa Rica, the decision of a single official will determine their future.

Our sincere thanks go to the author of this piece, journalist Marco Adrián Vega Botto, for this extraordinary contribution