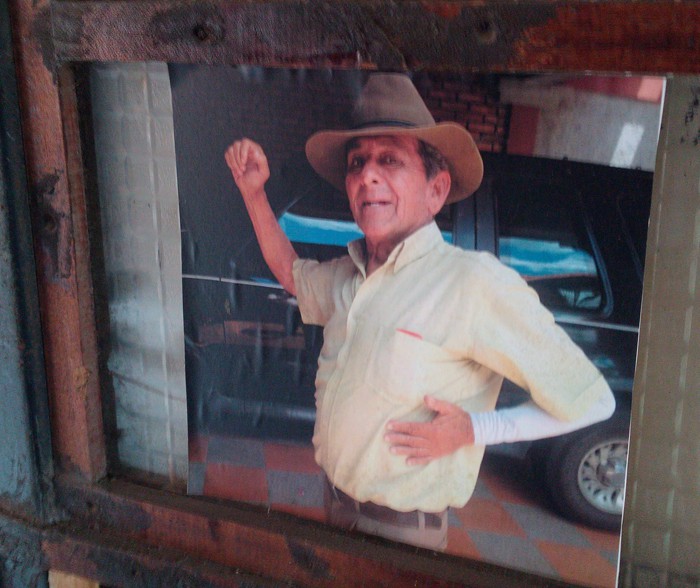

SANTA ANA, San José — The soul of this place comes alive when viewed through the blue eyes of Héctor Aguilar — architect, antiques dealer and prolific profiler of town characters.

“The personalities come looking for me here, and they say, ‘I want to be on your page,’” Aguilar said, standing in front of a wall full of photographs of locals he has interviewed, videoed and featured on his much-clicked Facebook page. “People from the street, bus drivers, famous people, dancers, singers, unique people, lottery ticket sellers, special people with mental problems, all kinds.”

He showed me a video of some bailes típicos, traditional dances, that had been viewed 24,000 times — this in a canton with a population last measured five years ago at under 50,000.

Aguilar, 55, is a Santa Ana antiques dealer who owns the Galería de Antiguedades Santa Ana, a block away from the central church. It’s a sprawling display of old bicycles, telephones, record players, typewriters, tools, license plates, advertisements and other collectibles.

“The way I see it, old things are forever,” he said. “And as an architect I like the design of old things, very creative designs and of very good materials, not recycled, pure.”

Aguilar knows a thing or two about design, as he has been an architect for 27 years, about half of those as municipal architect of Santa Ana. In fact, he designed the Red Cross building universally used to give directions in this town, and he is designing a remodel that will add a third floor.

Town father

But Aguilar seems to be gifted with an aesthetic sense that transcends visual space, one that also holds a deep appreciation for time, and above all celebrates people.

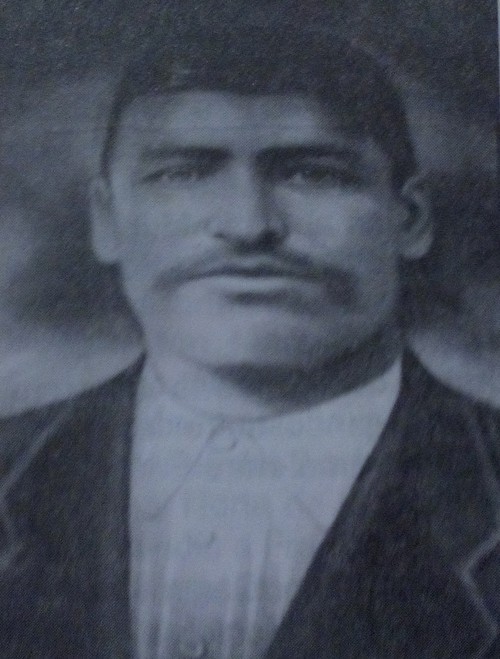

“My grandfather was the founder of the town,” he said, referring to his abuelo Pedro Aguilar Herrera. “He was the first municipal president that we had in Santa Ana.”

Indeed, Pedro Aguilar’s picture appears in “Santa Ana: Sociocultural Resources,” a history of Santa Ana by Jorge Acevedo, where he is listed as first president of the municipality, elected in 1907, and an hijo predilecto (favorite son) of Santa Ana.

“He lived in Escazú, and at that time Santa Ana belonged to Escazú,” said Héctor. “My grandfather fell in love with my grandmother, who was named Dolores Saenz, known as Doña Lola, a santaneña. So my grandfather came to Santa Ana a lot to woo my grandmother, and he fell in love with this town more and more.

“So he got a group of residents together and said, ‘Why don’t you proclaim independence from Escazú?’ And that’s how he headed the first independence movement of Santa Ana. And they declared him persona non grata in Escazú, so he couldn’t go back there. He came and he married my grandmother here, and the first Municipal Council was founded, of which he was the first president.”

Pedro, a farmer who founded the first bakery in Santa Ana, had an astonishing 13 children, of whom 10 died of incurable fevers — typhoid, yellow fever and cholera, Héctor said. The remaining three were the oldest daughter, who founded the popular El Coco Restaurant; a middle son, who was a choirmaster at the church and a professor of music; and the youngest son, Héctor’s father, an onion farmer who also served on the Santa Ana Municipal Council and founded the Centro Agrícola Cantonal, a farmers organization.

Héctor was born at a hospital in San José in 1960 but has lived his entire life in Santa Ana, though he spent 10 years attending the University of Costa Rica.

Why 10 years?

“Because I started out studying agronomy and then switched to architecture,” he says.

Aguilar’s first job was as municipal architect of Santa Ana, where he designed not only the Red Cross building but the gymnasium of the downtown Andrés Bello López school, as well as churches in nearby Matinilla and Barrio España.

He eventually opened his own architecture firm, which he still runs out of an office next door to the antique shop that he shares with his wife, Eduviges Jiménez, an attorney from Piedades.

When Aguilar’s father died he inherited the house in which he grew up, where the antique shop stands today.

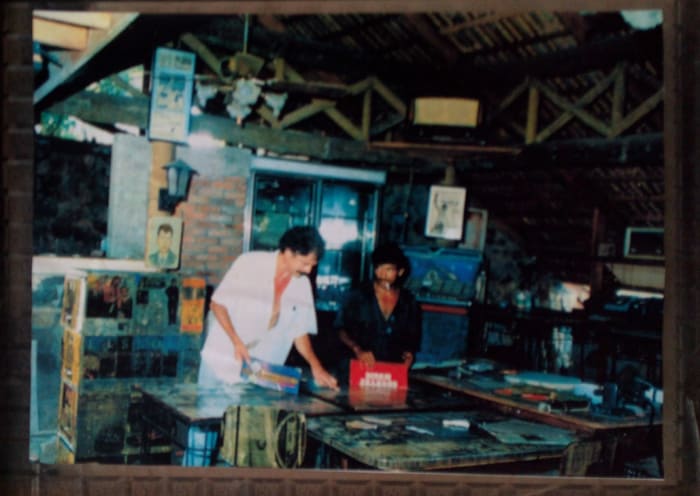

“And I put in a restaurant, it was called El Tejado de Toño, in his honor, because the place has lots of tejas.” Tejas are red roof tiles, and Toño was the nickname of his father, Antonio Aguilar Saenz.

The restaurant, which opened in 1990, served traditional típico food, and Aguilar decorated it with the antiques he had been collecting for years, not unlike an American-style roadhouse. But after five years he closed it down.

“It’s a very complicated business, very difficult, very stressful, very enslaving,” he said. “I didn’t like it, really. And so I decided to close it. … Once I closed the restaurant, I stored the antiques in a bedroom and they started deteriorating because of dust, rust, etc.”

For over 15 years Aguilar used the property just to rent apartments. But three years ago, he decided to dust off his vast collection of antiques, hang out a shingle and put them on sale.

Thus was born the Antiguedades antique store in the home where he crawled around as a baby.

So where did he get all this stuff?

“The people bring it,” he said. “They learn that the place exists and they say, ‘Don Hector, I have some furniture I don’t know what to do with, I can leave it for you to sell?’ ‘Sure.’

“I don’t need to leave, to go out treasure hunting, no. The treasure comes to me.”

Back when he was running the restaurant, he said, people would come and see that he liked antiques. “And they would bring me things,” he said. “Some I would trade for food or drink. Others would just say, ‘Keep it.’”

So how’s the business doing? Great, he says.

“It’s the only and the largest vintage antique gallery in the western San José area,” he said. “There may be others, but there’s none as big as this.”

Santa Ana’s unofficial historian

So we have Aguilar the architect and curator of antiques — an expert in the visual design of things. But what endears this man to his pueblo is his love of people.

And here, too, he has catholic tastes; he collects personalities old and new, and he’s friendly with both the illustrious and the downtrodden.

“You can see it all on my page,” he says. “There’s Pedrito, who sings and sells lottery tickets. The people love him a lot.”

Pointing to his wall of pictures, he said, “This is a singer who recorded a famous song called ‘La Avispa,’ Alex Guerrero. He’s from here, and it was the most famous popular music record in Costa Rica. … He died of drinking liquor, of cirrhosis.”

Another picture: “This band, which is from Santa Ana, it’s from 1973, it’s called Vía Libre. … It’s the most famous group in Costa Rica and it’s from Santa Ana. They’re the Beatles of Costa Rica. The Tico Beatles.”

Another picture: “This is the most famous dancer in Santa Ana. His name is Mario, they call him Mario Yuca. He’s famous for dancing in the dance halls: swing and Creole swing and pasodoble, all that.”

Aguilar saved the best story for last. Marcial Aguiluz, a laborer from Honduras, became one of Santa Ana’s most famous citizens after he moved here and married a rich man’s daughter in Lindora, today’s multibillion-dollar business strip between Santa Ana and Belén, sometimes called the “Golden Mile.”

Aguiluz is portrayed today on a bust outside City Hall. He is a “favorite son” of Santa Ana like Aguilar’s grandfather, and he has his own Wikipedia page. But to hear Aguilar tell it, he was a deeply flawed figure who married a very rich daughter.

Aguiluz had traveled from his native Honduras to Mexico, where he was inspired by the Mexican Revolution, and then fought in revolutionary movements in El Salvador and Honduras before arriving in Costa Rica in 1942. Here, he met Florentino Castro.

“(Castro) was the richest man in Costa Rica in his day,” Aguilar said. “Lindora was then just a finca that belonged to him; all of Lindora, Pozos, everything. And he had about 15 fincas around the Turrialba Volcano.

“(Castro) had a cheese factory in Lindora, and he brought Marcial (Aguiluz) to make Honduran cheese,” Aguilar said. “But Marcial was very intelligent, and the daughter of the owner fell in love with him. And she suffered a lot, because Marcial was a big womanizer — lots of women and liquor.”

After some cheese-making and some love-making, Aguiluz became a player in the revolutionary army that brought José Figueres Ferrer to power in the 1948 civil war. He later served in the Legislative Assembly and helped found the communist-leaning Partido Acción Socialista (PASO).

According to Wikipedia, Aguiluz inherited the property of his wealthy father-in-law Florentino Castro and eventually donated it to various civic causes.

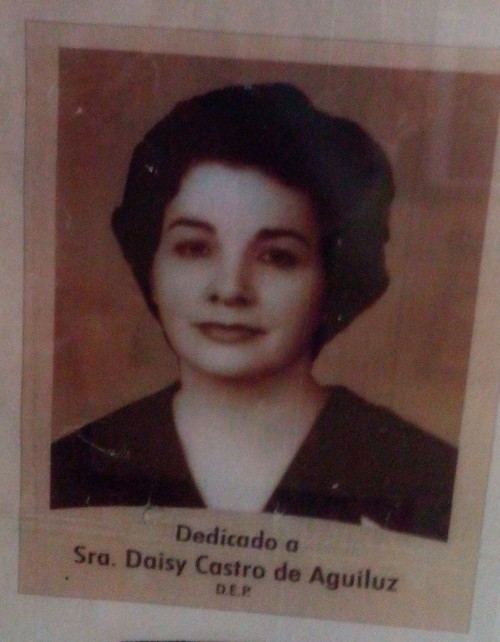

But Aguilar says, “No, Marcial didn’t inherit that property, the daughter did.” The daughter, Marcial’s wife, was Daisy Castro.

“But Marcial is very machista and he took over, and he sold pieces of the finca to drink liquor, and he would sign for the woman,” Aguilar said. “She ended up going crazy at the end and suffering … because he had lovers and lots of children, and to all his lovers he left children. And to all his children he gave land that wasn’t his.”

This is how it went down, Aguilar said.

“(Marcial) would go to a bar and start drinking liquor in the bar, and the owner would say, ‘Sign.’ ‘How much is it?’ ‘It’s 15,000 colones, just sign for me here.’ And he would come to the bar the next day and start drinking again. ‘How much is it?’ ‘15,000.’ ‘OK. Today is my birthday. Everyone who’s inside, stay here, and close the door.’

“Mariachis came, and they had a big party, all on his account, and finally the owner said to Mar, ‘Look, your bill is now 200,000 colones.’ ‘That much?’ ‘Yeah, look, here’s your signature.’ ‘Oh, OK, come with me, and I’ll give you land.’ So they’d go to a lot, and he’d said, ‘I’ll pay you with the lot.’”

So Marcial was paying for liquor with land? Exacto.

“So all the women looked for him because he paid their way,” Aguilar said, “And they let him give them children because they knew he would leave land to the child.”

But isn’t Marcial a big hero in Santa Ana to this day, with a bust outside City Hall?

“He was a beloved figure, because he was very happy,” Aguilar said. “And he was very generous; he gave everything away. But it wasn’t his.”

You get the feeling that Aguilar wouldn’t judge this rogue any more than the gallery of random street people on his wall. It’s not his job to judge.

He just knows the real story.

Contact Karl Kahler at kkahler@ticotimes.net.