After National Liberation Party candidate Johnny Araya announced he was no longer campaigning for president in a second-round vote, many journalists and politicians questioned why a runoff election was necessary at all since his decision effectively gave the presidency to Luis Guillermo Solís of the Citizen Action Party.

Costa Rican law prohibits any of the two candidates in a runoff election from stepping aside. The constitution demands that the Costa Rican people vote on April 6. Voters will weigh their options and freely decide who is the best. The decision is theirs to make, and the future belongs to the voters, not the Legislative Assembly or a candidate who steps down. Only the people can make this decision.

Candidates can withdraw from the race during a first round, but once entered into a second round, they are legally required to finish the process. This is not a whim or some old, unrevised piece of legislation; it was established after two bitter experiences in the country’s past. The people must vote, and a mandate must be given. Yes, it’s expensive and it may seem unnecessary, but democracy is funny that way.

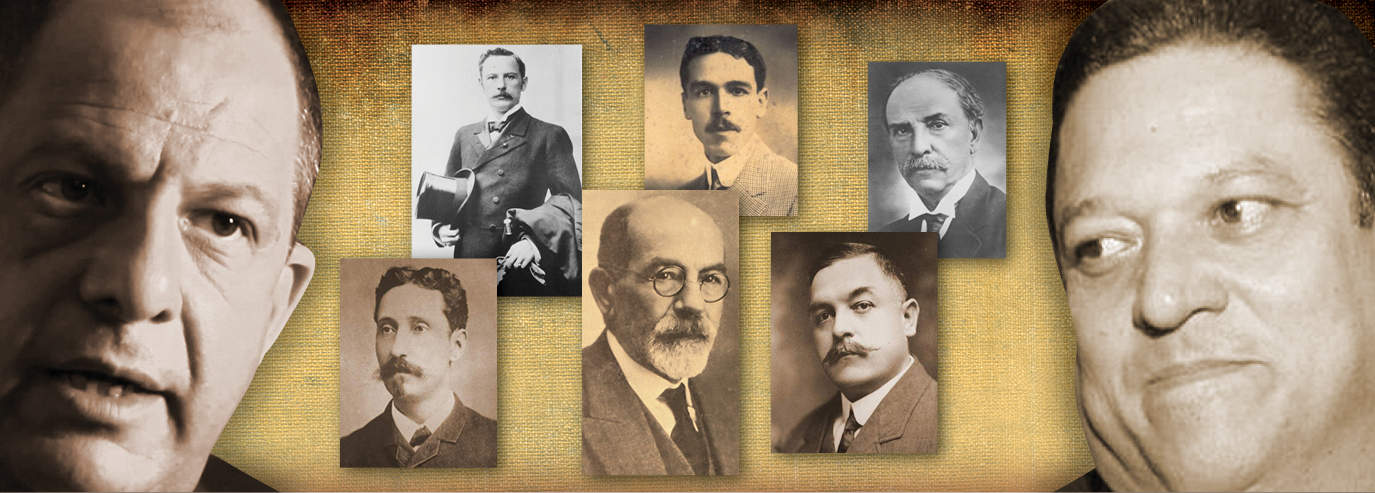

The 1913 presidential election

The 1913 presidential election was the first time adult Costa Rican men enjoyed direct “universal suffrage” and all the challenges that came with it.

The three main candidates were all liberals. Máximo Fernández Alvarado was the ruling Republican Nationalist Party’s political boss and had incredible influence among the popular sectors. Next was Carlos Durán Cartín from the National Union Party, a coalition representing the upper class and “the Olympus liberals” who gave shape to late 19th century Costa Rica and felt left out of the political arena. The third candidate was two-term former President Rafael Yglesias Castro, an aging career politician with a deep populist streak, who founded the Civil Party – one of the first in the country – and a direct descendant of “the Olympus” elite.

None gathered the necessary votes to reach the presidency. Fernández received 43 percent of the votes, while Durán received 30 percent and Yglesias 27 percent. According to the constitution, it was up to Congress to decide the new president.

Durán and Yglesias brokered a deal in which they would support each other in case of a runoff election. That put the ruling party in a tough spot. The Republican Nationalists were decidedly against Yglesias having any direct influence on the next administration. After long negotiations between the two remaining candidates and President Ricardo Jiménez Oreamuno, they chose lawmaker Alfredo González Flores as the next president in order to shut out Yglesias.

As the next step, the candidates withdrew their names from consideration, and the Assembly was then allowed to pick someone who hadn’t even placed his name on a ballot. González was an ideal choice. He was well known and respected by both parties and had an impeccable reputation as an honest and fair politician. He received control of the army even before Congress officially confirmed him.

This lack of legitimacy and the backroom dealings that prompted his selection tainted the González presidency from day one. The fact that González would push some of the most ambitious and far-reaching political reforms in modern history did not help matters. González was deposed in a coup three years later by his own secretary of the army and navy. The coup was welcomed by a voting public who felt no connection whatsoever to his presidency. Thus started one of the darkest periods of Costa Rican history: the repressive Tinoco military dictatorship.

The 1932 presidential election

In 1932, at the end of Cleto Gonzalez Viquez’s last period, the main presidential candidates were Ricardo Jiménez Oreamuno, ex-president and leader of the Republican Nationalist Party, and Manuel Castro Quesada of the splinter party Republican Union. Elections were held on Feb. 14.

Fearing the worst, on Feb. 15 Manuel Castro joined forces with Jorge Volio, a radical catholic priest who was head of the Reformist Party, and organized a coup. Ricardo Jiménez had been president twice already, while Cleto González was currently in his second term. On opposing sides of the same liberal spectrum, they seemed oddly at ease with each other. The country’s richest families were backing Jiménez, the same way they had backed González just four years before. Still, the opposition didn’t agree on enough to organize a common front against Jiménez, and they felt moments away from defeat.

Castro and Volio made their move on the morning after the election, even before the official results were reported. They got as far as taking over the Bellavista Fort – currently the National Museum – with the help of the military base’s commander. They weren’t as lucky anywhere else, and support quickly vanished. Yet they remained protected inside the building.

On Feb. 16, the results confirmed what Castro feared. Ricardo Jiménez received 46 percent of the vote, just shy of the 50 percent needed to win the election outright. A runoff election was to be held against Manuel Castro, who received only 29 percent of the vote. A group of opposition politicians managed to negotiate a pardon for Castro. He left the Bellavista fortress in disgrace and renounced his candidacy for the runoff election, saying he was unworthy after his anti-democratic behavior.

Ricardo Jiménez was declared president without a second election. He received no mandate and was not ratified by the public. Because he never had to engage those who backed other candidates in order to win their votes in a second round, more than half of the country felt unrepresented.

This lack of a consensus or unified direction set the tone for his presidency. During his watch, the Communist Party gained a foothold in Costa Rica, as no one else was supporting workers in their struggle for rights. The fascists spread their influence and were well represented in the political arena, which created tensions and resentment.

The radical pro-catholic movement also gained momentum and was savvy enough to make deals that would get them the presidency in the 1940 election.

The seeds of the 1948 Civil War had been planted.

Fo León is a writer with ties to the local political, art and music scenes. Mostly an observer, he has at times been a participant. He lives in downtown San José.

Recommended: Joining the ranks of the hopeful