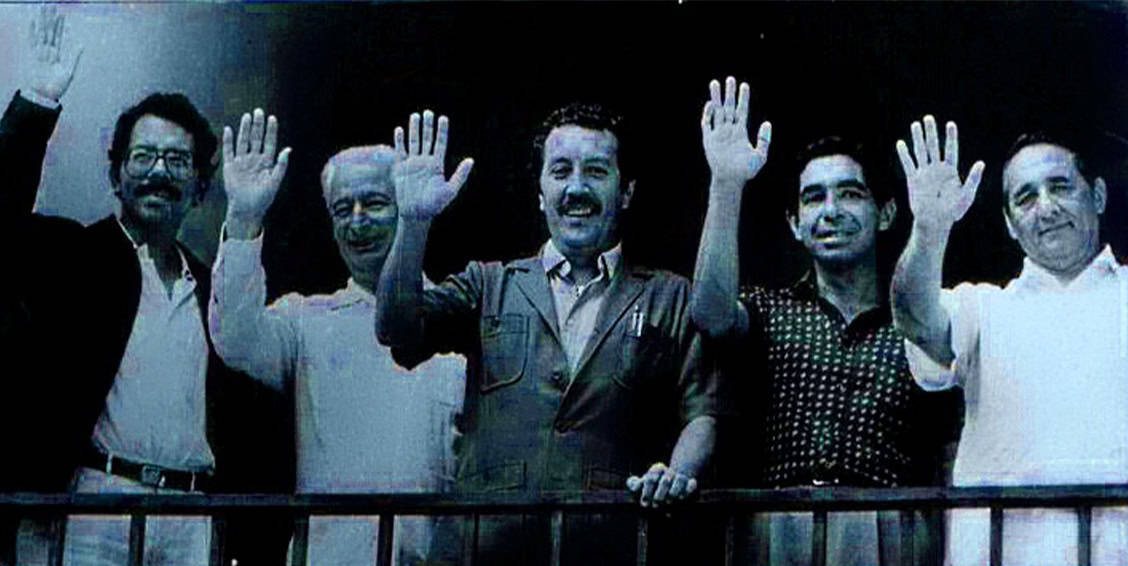

It is a time to honor history. The 25th anniversary of the Esquipulas II Peace Agreement, aka the Guatemala Accords, was commemorated this week at the National Theater in San José. Signed by five Central American presidents on Aug. 7, 1987, the accords brought peace, first to Nicaragua and eventually to El Salvador and Guatemala. They also extricated the United States from the worst effects of the Iran-Contra affair.

I write about these matters with a bit of authority. I witnessed it up close, knew the major players (or their lieutenants) and wrote a contemporary account, “War and Peace in Central America” (Scribners, 1989).

As Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state, George Shultz wrote in his memoirs that the driving force behind the peace was Costa Rica’s Oscar Arias, who shares credit with Guatemala’s then-president, Vinicio Cerezo. I also would cite two old friends, now dead: Arias’ principal Costa Rican collaborators, Foreign Minister Rodrigo Madrigal Nieto and the ambassador to the U.S., Guido Fernández.

There is much to write about, including how Nicaragua’s Sandinistas and their Cuban mentors misplayed their hand, the immense stupidity of the Iran-Contra affair, the rather different characteristics displayed by each of the three civil wars and the political tangle that the Central American wars became in the U.S. I will skip it all and go to the central features that made the Peace Accords important, even today:

1. The carnage in the warring countries and the likelihood war would spread to Honduras and Costa Rica. As a Salvadoran insurgent leader of Leninist persuasion put it, “Costa Rica, too, will have its hour of glory.”

2. The courage that Arias displayed in confronting the “Cabal of the Zealots,” as the U. S. Congress styled the authors of Iran-Contra.

3. The winning strategy crafted by Arias with Cerezo’s help. It was a strategy of “don’t let yourselves, country X, be snookered into being the last holdout against a peace agreement.”

Central America was one of the final two hot conflicts of the Cold War. It played no real role in the Soviet collapse – in contrast to the Afghan uprising against Moscow – but it was deadly for Central Americans. Arias’ predecessor, Luis Alberto Monge, had bought time for Costa Rica by declaring neutrality. That proclamation got slammed by U.S. “hawks,” though Monge had made clear he was talking about military neutrality, and would continue to advocate democratization as part of a peace settlement.

Any American with an ounce of sense who has worked in national security and foreign affairs knows that the U.S. doesn’t always get it right. The Contras were one such moment. By the time Arias became president, the pressures from the Cabal of the Zealots to turn Costa Rica into a Contra base on the order of Honduras had grown. Hawks were in the saddle of U.S. policy in Central America. (They were not – thank heavens – in charge of policy toward the Soviets. As Jim Mann’s lucid account in the book “The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan” makes clear, Reagan and Shultz pursued peace with the Soviets over the objections of the rest of Reagan’s advisers.)

The “hard right,” as Shultz styled them, wanted no part of peaceful settlement and preferred to fight to the death of the last Nicaraguan. This is the moment when analysis became art. Where the big boys of Contadora, Mexico and South America, supported by Europe, had failed, Arias would succeed.

He moved with Cerezo’s help, and in a crucial moment with the help of the president of El Salvador, Napoleon Duarte, to get one party, and then another, to agree to a simultaneous cease-fire, a cessation of arms shipments to insurgents, and in Nicaragua, peaceful elections sealed by the February 1988 cease-fire between the Sandinistas and the Contras at Sapoa, Nicaragua, on Feb. 7, 1987.

The Iran-Contra revelations and CIA Director William J. Casey’s fatal illness drove out the most wild-eyed conspirators, but the Reagan administration remained divided, while democrats, led by Speaker Jim Wright and Congressman Mike Barnes, supported Arias.

The deep anger of neoconservatives become public when Arias got the Nobel Peace Prize. Robert Kagan said his reaction was “unbridled disgust,” and an unnamed, more senior official (obviously Elliot Abrams) slammed the Nobel Committee for rewarding “an anti-American stance.” Shultz had to disown these comments in The New York Times the next day.

The point, however, is that while the U.S. government was divided, it took great courage for Arias to take on the hardliners, who cut off economic aid to Costa Rica for a considerable time. In the end, it was the administration of George H.W. Bush that ended the efforts to restart the Contras, a decision sealed by a meeting between Secretary of State designate James Baker and Speaker Wright.

Peace came to Nicaragua, and Violeta Chamorro defeated Daniel Ortega in free elections, effectively ending war in Central America, though fighting would continue for a time in El Salvador and Guatemala. No mean achievement.

By Frank McNeil | Special to The Tico Times

Frank McNeil served as U.S. ambassador to Costa Rica during the administrations of Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan.