For a book-lover who sometimes feels a bit constrained by the shrink-wrapped volumes in many of Costa Rica’s bookstores, the International Book Fair is unquestionably Christmas Day. For just over a week, the Antigua Aduana in downtown San José becomes a joyful explosion of weighty historical tomes and slim volumes of verse, colorful self-published offerings and obscure academic treatises.

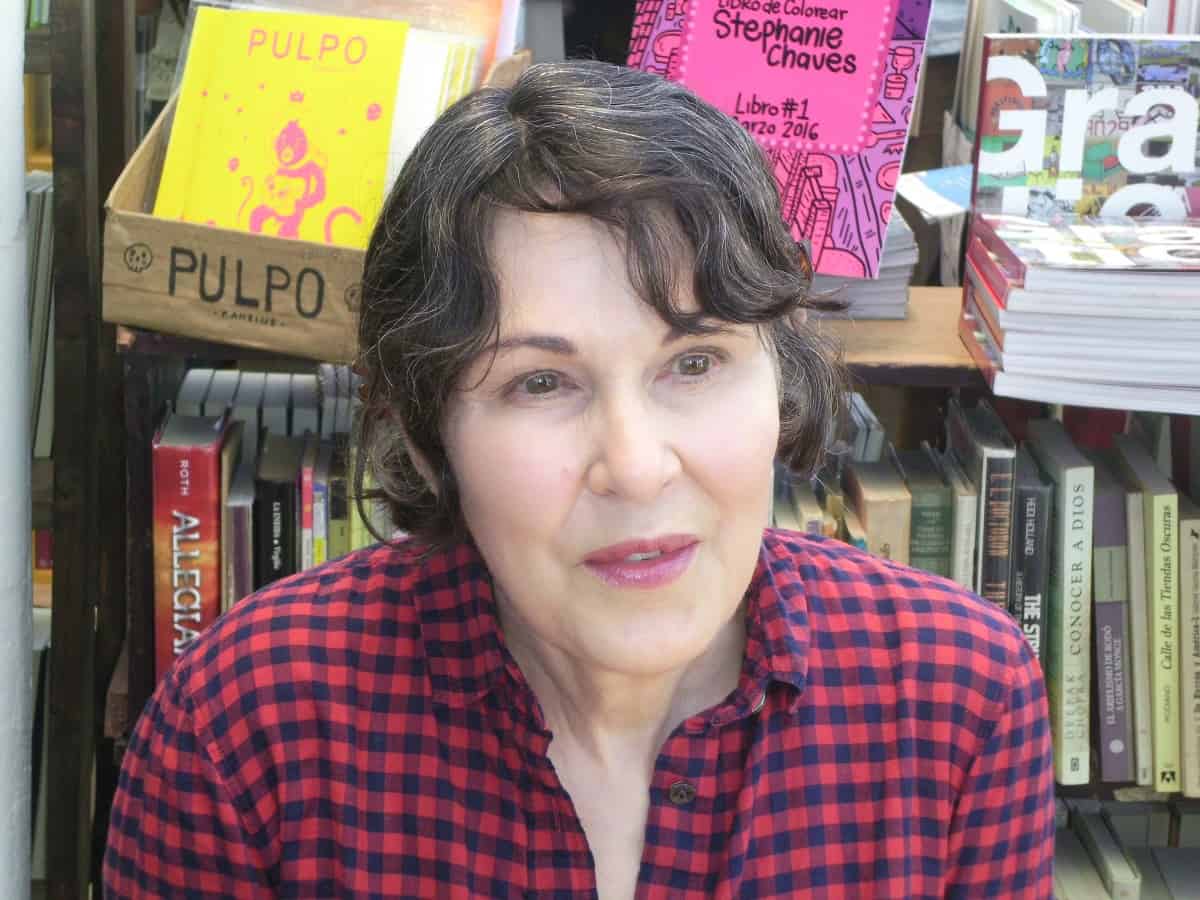

Of course, readers and writers wander the aisles as well, sipping coffee and window-shopping. In such a setting, it feels almost natural to run into acclaimed Missouri-based poet Mary Jo Bang near the glass doors at the entrance and sit down for a chat.

Bang, 69, became a published poet at the age of 50 after working as a physician’s assistant and a photographer. She is the author of works including “Apology for Want” (1997); the National Books Critics Circle Award-winner “Elegy” (2007), which chronicled the year following the death of her son; and the abecedarian collection “The Bride of E” (2009). She is the recipient of numerous fellowships and the Pushcart Prize (2003), and teaches at Washington University in St. Louis.

As bookworms bustled and browsed behind her on the second day of the fair, Bang spoke with The Tico Times about her days living abroad, the “Introduction to American Football” class she never took, and her obsessive quest for the perfect translation. Excerpts follow.

How has Costa Rica treated you so far?

It’s been wonderful. Every hour I find something new to be charmed by. I went to a gathering last night with various Costa Rican writers – there was a psychotherapist, an architect, someone who is just starting out as a creative writer, and somebody who is about to publish her first novel.

Your creative work took a big step forward when you spent time in England once your kids were grown. Did being far from home ignite your creative instincts in some way, as is the case for many immigrants or expats?

Yes, because you had to fill a day, which is a very odd experience for a lot of people. I was there with my husband, and the terms of his employment were that I couldn’t work. What that meant was that every morning I had to get up and make a life. That’s thrilling, but also challenging: What do you do?

I got to know London very well. I didn’t have any friends, so I would go on my own to a museum or some kind of architectural feature, and read about the history of it. If I had an idea, I would have total freedom to explore that idea for days. It was a life of structured leisure and self-education, and I’d never had any opportunity like that. I had a child when I was 20 and always had to work, so I had never had the full-time student experience, or the student who goes to Europe and discovers the world. There I was much later, and in some ways better able to make use of it.

Right. Give someone who has already been a working mother that kind of time, and she’s going to do something with it.

Well, if she has something she’s always wanted to do.

You wrote a piece about how writing may be in our genes. Was writing a thread throughout your whole life, even if it was less of a priority at some times than others?

Reading was the thread. For a lot of people, reading makes you want to write, because there’s a compulsion to add your ideas to those you’ve just encountered on the page. Even though I didn’t have the time to write or the resources to learn how to write well, it was a dream, almost a preoccupation. Later, when I became a photographer, I would frame whatever was around me as a potential photograph. With writing, I kept framing scenes and imagining characters, but I never felt I knew how to put that down on paper.

Then I fell into an opportunity. [While living in Evanston, Illinois], there was a class being offered at Northwestern University, in 1980: a new program for women. They were going to offer three classes. One was a history class. Another was a class on football, so that you could watch football with your husband and understand the game. The third class was going to be creative writing.

Wow. Did you take the class on football?

No! [Laughs.] Just the creative writing. … I loved it, but it was also painfully frustrating, because I didn’t feel that I was learning how to solve the problems in my writing. Then one day I wrote a poem, and compared to writing fiction, it was very easy. All the writing I had imagined began to take the form of poetry. I was able to learn, and get better and better.

Social media, and the internet in general, is having such an impact on writing – both publishing and format. It fades the line between the unpublished and published, but one could also argue it leads us to have shorter, blog- and tweet-sized thoughts. Do you think it has a smaller impact on poetry than other genres?

I think what it does is introduce the poet to a plurality of modes and voices. Prior to social media, you were introduced to poetry because you knew someone who knew a few poets, or your teacher guided you. Now, you can see that a poem can be so many different things. … The Academy of the American Poet has a listserv that sends out a poem from a living poet on each weekday, and on the weekend, a dead poet. Every day, no matter what your own aesthetic preferences are, you can see examples that represent a wide swath of aesthetic difference. There’s also the Poetry Foundation in Chicago. It’s an incredible education.

I’ll be more traditional: who are your favorite poets?

I love Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Lord Byron — and there are many poets that I’m interested in, which is slightly different. I’m interested to see how today’s poetry evolved from yesterday’s, all the way back to Homer, Sappho, Horace. Literature is the history of how different people put language together. That’s what entertains and fascinates me.

I’m also very interested in mystery. If something is said too simply, you never have to read it again. But if you have to interrogate the words to find out what they mean, it’s going to be an active process, not passive.

Literature [can make us] feel that we are in the presence of another human being — a human being who is willing to talk about things other people might not be willing to, like our own mortality, or our broken hearts, or the loss of a loved one. How each person does that and the weight of the words they use will engage different people differently.

But to do that, it has to stay a little bit open. If as a poet you are tyrannical about what it means, it only mirrors what a few people feel. If you have some kind of mystery or openness or fluidity, then it becomes a mirror that people can see themselves in.

I can see why you love translation.

Yes. My translation of Dante’s “Inferno” came out in 2012. Now I’m working on a translation of a Japanese poet who wrote between 1927 and 1937, a surrealist, Shuzo Takiguchi. I’m doing that with a young Japanese man, Yuki Tanaka.

How familiar are you with Japanese?

Not at all, but I’m learning a lot. Japanese is a very spare language, so if you do a word-for-word translation, you reduce the meaning significantly. … Fortunately I have this kind of compulsive personality and perfectionist standard. Even now we’re returning to some of the poems we translated two years ago, or even poems we’ve already published, and finding new ways to solve the problem in the original.

There’s a phrase in one of the poems: “night’s perplexing handcuffs.” Suddenly it became apparent to me that if you use “cryptic” instead of “perplexing”… a crypt is underground, which matches “night,” and one of Takiguchi’s recurring themes is “what’s hidden.” That’s what we aim for and what we keep improving on.

I imagine you walking down the street and suddenly yelling, “Cryptic!”

Yes, those Eureka moments. But they only come after months or sometimes years of continuing to go back to that poem in your mind.

Are you working on a new volume of poetry as well?

I have one coming out next year that will be called “A Doll for Throwing,” inspired by Bauhaus photographs or ideas, or people who participated in the Bauhaus movement, especially Lucia Moholy, who took some of the early photographs and was the first wife of one of the teachers, László Moholy-Nagy.

He, of course, became very famous, and her name for a time was relatively forgotten. In the Bauhaus, they constructed a doll … and one of the descriptions of the doll at the time was, “No matter how you throw the doll, it will land gracefully.” That’s a fact: life often throws us, but the key is landing gracefully.

The International Book Fair continues through Sunday, Sept. 11 at the Antigua Aduana in east-central San José. Visit just to stroll through the aisles and browse titles from publishing houses both large and small, or check out a workshop or lecture. The jam-packed agenda includes panel discussions, storytelling for kids, and much more.