When it comes to Costa Rica’s global competitiveness, we all want and need more people who are able to communicate effectively in English, as there is a direct correlation both here and abroad between the number of meaningful job opportunities and the English-language proficiency level of the workforce.

Therefore we need to ask some important questions:

1. Are we educating today’s workforce sufficiently in English to obtain jobs that are currently available?

2. Are we on the right path to develop current and future workers’ English capacity for future jobs?

3. Lastly, what can all of us – not just classroom teachers and national education leaders – be doing to help raise the overall English proficiency level of Costa Rican citizens?

Companies in Costa Rica that seek English-speaking employees generally identify two main language level requirements depending on the specific functions of the job. Based on Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) terminology, where there are six total levels ranging from beginner to advanced (A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2), jobs with minor speaking and writing needs would warrant a minimum B2 level while more advanced and frequent needs for communication would merit a C1.

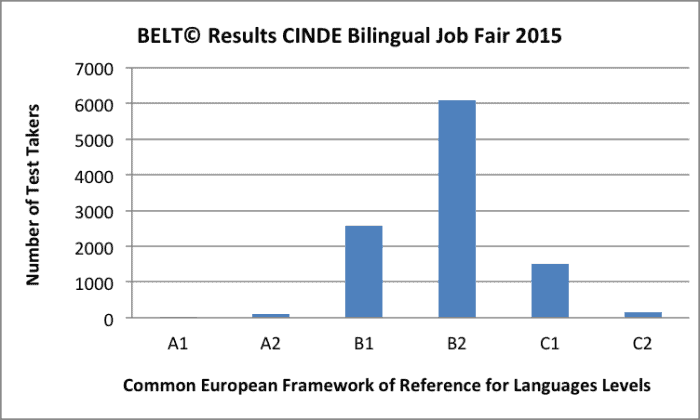

At Idioma Internacional, our team of experts developed an English-language proficiency assessment aligned to the CEFR, and offered it to participants of the Costa Rica Investment Board (CINDE) Bilingual Job Fair (CJF) in 2014 and 2015. The exam, called the Business English Level Test, or BELT©, provided instant and reliable feedback to job candidates and gave the hiring companies that interviewed them a reliable measure of their English communication skills. The first year, participation in the test was voluntary among attendees, and 2,557 of the 13,000 attendees participated; this year, 10,444 people took BELT© as a registration requirement, and 9,800 attended the fair itself.

Results showed from this career-focused population – candidates seeking jobs at a CINDE bilingual job fair – that only 1 percent of test-takers scored in the A1 (low beginner) and A2 (high beginner) levels combined. A total of 25 percent of the job-seekers scored at the B1 (low intermediate) level, and 58 percent scored B2 (high intermediate), 14 percent at the C1 level (low advanced), and 1 percent at the highest level, C2 (high advanced).

These results reveal three important points about the current state of English proficiency for job candidates in Costa Rica.

1. We’ve got a lot to work with – but we’re not there yet.

These numbers show we’re not starting from scratch. Years of investment and effort in language education in Costa Rica haven’t been for naught. However, this is the cream of the crop, a self-selected population believing they have enough skills to compete for bilingual or multilingual jobs. When only 25 percent of this elite group scores below the minimum level many companies require, and 85 percent fall below the level required of the best jobs, we’re talking thousands of missed opportunities, both for these individuals and for the country as a whole. And that’s only a short-term view. The bar is constantly being raised for bilingual workers, with many companies now looking for a C1 minimum English level along with two or more other languages, so we are setting ourselves up for even bigger failures in the future if we don’t take action.

2. It wouldn’t take much in the short term to get additional people hired.

We can focus on two areas right now that can make an immediate impact on current job-seekers’ success and opportunities: provide support to the 25 percent (B1) of job-fair test-takers who scored just shy of the hiring minimum and the 58 percent (B2) who lack the English level for a higher-paying job. If public and private institutions worked together to identify and train these candidates in the specific skills necessary to make the B1 to B2 and B2 to C1 jumps, one level on the CEFR for each group, Costa Rica would significantly reduce the personnel shortage that causes some companies to turn elsewhere in search of bilingual candidates, while also creating the potential for even higher paying jobs for the Costa Rican workers of the future.

3. Collectively more needs to be done to move these numbers forward.

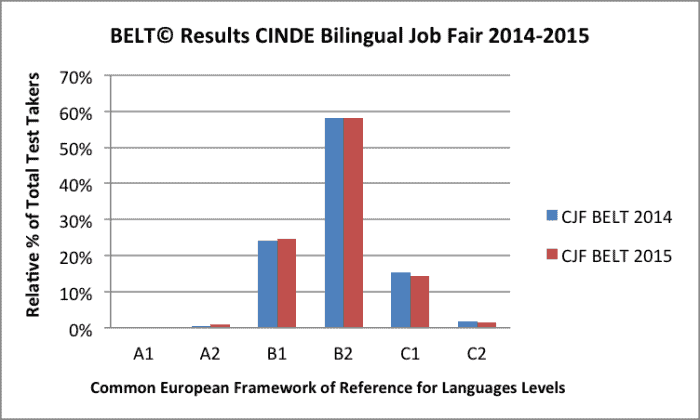

One of the most remarkable findings from the CJF BELT© results was the fact that from 2014 to 2015, despite a big increase in the test population size, the results were virtually identical with respect to the relative percentage of English proficiency levels year to year. In two of the levels, the result was exactly the same; in the rest, it moved only 1 percent, some up, some down.

While one can’t expect drastic jumps in a single year, these two snapshots suggest that these job-seekers, many of whom attend the fairs in consecutive years, are not showing any significant increases in English proficiency, despite concerted efforts being conducted nationwide to improve the population’s overall English level. This is a call to all of us to do more. Policymakers at the Ministry of Public Education (MEP) and National Learning Institute (INA) are generally assigned the lion’s share of this burden, and rightly so. However, everyone involved in this issue has a responsibility, too.

Private language institutes need to do more in terms of offering scholarships, improving their teaching quality, and reaching out to a broader community through pro bono work. Individual language teachers and native speakers need to volunteer in higher numbers. The companies that need bilingual staff need to contribute more as well; this is a two-way street. A company that has chosen to invest in Costa Rica gets greater returns on that investment – bolstering its position within its community, the quality of its hires and employee loyalty – if it helps both prospective and current workers to continually improve their foreign language skills.

Finally, it’s never too late for the individuals themselves to take up the effort and put in the individual practice required to achieve advanced English levels. Classes are always helpful; however, they are not the only solution. Personal motivation and dedication are the most important factors to improve. Access to English resources and options to practice are ubiquitous with the Internet today, and it’s up to students of all ages to take advantage of those.

Improving English levels for people in Costa Rica is a complex task. However, it is essential and attainable if support is provided and people put in the effort. With continuing improvements to the foundation that has been laid in English education in Costa Rica, the country can be well positioned for a prosperous future.

Brian Logan is the founder and general manager of Idioma Internacional, specialists in Corporate English Training and Evaluation services, in San José, Costa Rica (www.idiomacr.com).