See also: Latin American leaders hail renewed US-Cuban diplomatic relations

Among the sharpest memories Guillermo “Bill” Vidal has of being sent from his childhood home in Cuba was waiting in the airport. There he was in 1961, he and his two brothers and so many other kids, distraught, excited, scared, separated from their parents by glass.

“It was terrible,” he said. “It was called La Pecera, the fishbowl, and all the people leaving would be put inside the waiting area and the parents would be on the other side. They would be looking at you through the glass of the boarding gate. We were on one side and we would touch the glass and they would put their hands on the other side and mouthing ‘I love you.’ ”

Like many Cuban Americans, Vidal now looks at President Barack Obama’s announcement that the United States will seek to reestablish diplomatic and economic relations with Cuba with nuanced feelings. In many cases, they are overjoyed. In others, skeptical. Some are of a generation that still hears the voices of their parents, who believed Fidel Castro robbed them and should be punished until the regime collapses.

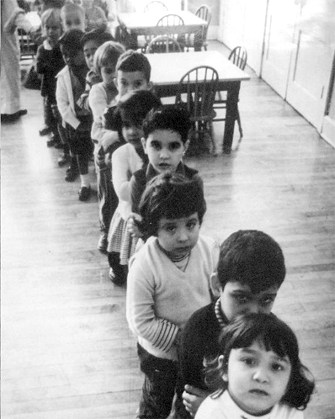

In the first years following the revolution and Castro’s seizure of power from dictator Fulgencio Batista, 14,000 children like Vidal left Cuba for the United States, under the auspices of the Catholic Welfare Bureau. They were relocated with relatives or placed in foster homes and orphanages. Operation Pedro Pan, the exodus was called. Peter Pan kids, they would come to be known. Many were joined by their parents later. Some were not. They would grow up to become professors, lawyers, doctors, business and city leaders, or, as in Vidal’s case, a mayor of Denver.

“We never thought we would be here forever,” said Ledy García Eckstein, whose parents sent her and her brother to the United States in August 1961. “I mean never. We lived in Iowa, my mom was there for I don’t know how many years, and she wouldn’t let me buy an electric beater. She would say, ‘I don’t [want] to be burdened by all that stuff when I got back to Cuba.’ ”

Vida’s father was of the same mind: “He called life in the United States exile and when you are in exile, you can never plant roots. You can never establish relationships. We were as Americanized as you could get. We were going to high school and college. We were looking at a future in the U.S. and they were looking at a future in Cuba. When they sent us away, Papí said, ‘We’ll see you in a couple of months.’ ”

Vidal and Garcia Eckstein greeted the news of closer ties between the United States and Cuba after decades of embargoes as a development long overdue.

“Whatever we can do to normalize relationships is what I want,” Garcia Eckstein said. “As a student of politics, I know that a policy that doesn’t work for 50 years or more is a policy you don’t keep doing. It doesn’t make sense. The purpose [of the embargoes] was to get rid of Fidel and [brother] Raúl [Castro] and it hasn’t worked, so let’s see what we can do to help the people of Cuba back into the 21st century.”

María Halloran’s parents sent her to the United States on April 20, 1962. It was just before her 12th birthday and she would wind up in an orphanage in Denver. Her parents joined her a year and a half later.

“And like everyone else, we did not think we would stay here because previous regimes were short-lived and here we are 52 years later. But I never thought what happened today would happen in my lifetime,” she said pausing, her voice breaking. “We had given up. We really had.”

The move announced Wednesday has not been universally praised throughout the larger Cuban community. Alfonso Aguilar, executive director of the American Principles Project’s Latino Partnership, a conservative political advocacy nonprofit group, blasted the decision, calling Obama naive. “The truth is that renewed American economic activity in the island will only help the regime line its pockets, and thus strengthen its repressive hold on the country,” he said.

Upon hearing Aguilar’s reaction, Vidal was quiet for a moment and then said he felt “great reverence for that opinion. It was my father’s opinion.”

“My father felt he gave up everything and that he was living a life that was not of his own choosing. . . . But under current policy, [it] is the common people who are suffering,” he said. “. . . The embargo was cruel to people who are not responsible for the government in place.”

Related: White House travel exemptions to Cuba do not cover tourism

Nelson Valdés, a writer and a retired professor who taught at the University of New Mexico, is not as certain. His stepfather sent him to the United States on April 13, 1961, four days before the Bay of Pigs invasion. He was 15, a teenage boy with wanderlust, under the influence of François Truffaut and his movie “The 400 Blows.”

But Valdés believed, as many others did, that he would return to Cuba. He did, eventually, in 1977, when President Jimmy Carter tried to do what Obama is trying to do now. It was a controversial move to defy the anti-revolutionary zeal and return to Cuba but all this informs Valdés’s view that, while the president’s message is “generally positive,” it also carries with it the distinct odor of paternalism.

“The very concept of ‘normalizing’ relationships is a very peculiar one, because Cuba has never had normal relations with the U.S.,” he said. “What may be normal from a U.S. viewpoint may not be normal from the Cuban.”

Washington Post staffers Danielle Paquette and Jonnelle Marte contributed to this report.

See also: Pope leads global praise for ‘historic’ US-Cuba rapprochement

© 2014, The Washington Post