In 2004, J. Maarten Troost burst onto the travel-writing scene with his first book, “The Sex Lives of Cannibals.” Troost was lovable for many reasons: He was a Gen X slacker, but inspired enough to live in the South Pacific. He was funny, but not hyperbolic. He was Dutch, but not really European – more like a bumbling Englishman with a hemp necklace. He was smart, free-spirited and utterly fun.

It’s hard to believe that Troost only has been famous for nine years. His books seem like a longstanding part of the expatriate canon, alongside Bill Bryson and Paul Theroux, exotic travelogues you can comfortably read in an airport lounge. Troost has an easygoing shtick: He spends time in far-flung places, either as explorer (“Lost on Planet China”) or as resident (“Getting Stoned with Savages”). These thoughts and actions are distilled into pithy essays. He sips a shell full of kava, hallucinates for days, and then writes an entertaining anecdote about it. Add a title rife with shocking words (“lost,” “sex,” “savages,” “stoned,” “cannibals”) and you’ve got a New York Times bestseller.

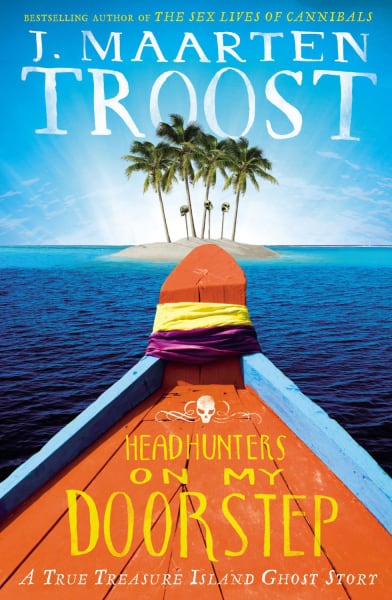

But don’t let his latest title fool you: “Headhunters at My Doorstep: A True Treasure Island Ghost Story” is a very different kind of book. In less than a decade, Troost has aged dramatically. In the book, he is married now, a father, and – it turns out – a raging alcoholic. “Headhunters” takes place again in the Pacific, but the book is largely a memoir of addiction and recovery. Entire chapters are devoted to his AA meetings, detox and brief switch from vodka to ganja. Now clean and sober, the author yearns for a fresh start, but the tropics aren’t just a spot on a map. In “Headhunters,” Troost returns to the last place he was happy.

For page after page, Troost cocoons himself in wit and observation, which is refreshing if you’ve ever slogged through the average addiction-and-recovery memoir. In his quest for healthier living, Troost (literally) follows in the footsteps of Robert Louis Stevenson and Jacques Brel, Paul Gauguin and Thor Heyerdahl, eccentric men who found themselves in the maritime equivalent of nowhere. But beneath these layers of curiosity and digression lies a very painful story. When Troost recounts his wife’s ultimatum (to enroll in rehab or leave), the tone is light, but the subtext is deadly serious, and so, we imagine, was the actual event.

Here is the paradox: Troost’s writing style has remained the same, a breezy, self-effacing prose with jabs of social commentary, yet the man himself has grown far more mature. Would he be as interested in Brel’s cancer diagnosis – and Brel’s decision to run away from treatment and sail around the world – if Troost himself hadn’t faced mortality? Would he have read Stevenson, a dense Victorian author, in his younger years? Would he feel quite so stridently disgusted by Gauguin, an infamous pedophile, if he didn’t have children himself? When he sees some kids playing in shark-infested waters, and their parents seem unconcerned, Troost reassesses his own role as a father. Is he overprotective? Should he let the young’uns run free? And – more to the point – would the author of “Getting Stoned with Savages,” only six years distant, have anticipated such a middle-aged crisis?

Fans likely will be divided into two camps: the ones who liked the old Troost, loafing and dreamy and boozy, and the diehards who don’t care what he writes about, as long as they enjoy themselves.

For droves of Costa Rican expats, “Headhunters” will chime with familiar themes. Years ago, Troost wanted to escape the First World grind, and he found an out-of-the-way tropical paradise to do so. He wanted sun and adventure and colorful new friends. Now, Troost is a famous author who is trying to outdo his demons. He takes up running and brushes up on his French. He remembers his childhood love of “Kon Tiki” and now feels critical of its flawed Swedish captain. All kinds of expats will see themselves in Troost: wide-eyed children who grew up, ran away, made serious mistakes, and redeemed themselves in a global way.

Halfway through the book, Troost injects a literary quest, and the somber narrative finds some momentum. Troost distracts himself with Stevenson’s biography and the “Treasure Island” mythos, and he starts to sail away from 12-step anguish.

If you’re a cynical reader, you could argue that Troost is the ultimate sellout. In a way, he has written the same book three different ways and exploited his own addiction for new writing material. It’s hard to say whether his Stevenson kick is genuine. “Headhunters” might strike the reader as an agent’s suggestion, a sellable idea that Troost went along with, because a sequel was just about due.

Yet Troost’s saving grace is his affable personality. He really is a pleasure to read, no matter his subject. For mainstream readers, Troost’s gift is the ability to educate, entertain and inspire simultaneously. For expats, “Headhunters” describes the sensations we often fail to verbalize ourselves. Between the lines, some gravity emerges, for even escapists must haggle with weighty situations. After years as the consummate escapist, a recovered Troost has apparently grown up.