Marie Claire Arrieta is a leading scientist and researcher in the area of microbiology. She was born in Tibas, San Jose Costa Rica in 1978 and studied microbiology at the University of Costa Rica. Marie Claire completed her master’s and doctoral degrees at the University of Alberta and continued her postdoctoral studies at the University of British Columbia.

She currently works as an academic researcher and professor at the University of Calgary. Marie Claire’s field of research is the gut microbiome — the vast community of microbes that inhabit the intestines and how our health depends on the health of our microbiome.

Marie Claire’s research has discovered changes in our microbes related to the onset of asthma, a disease that until now had never been studied from this point of view. These pioneering discoveries have revolutionized the study of this disease and opened up the possibility of predicting and preventing it.

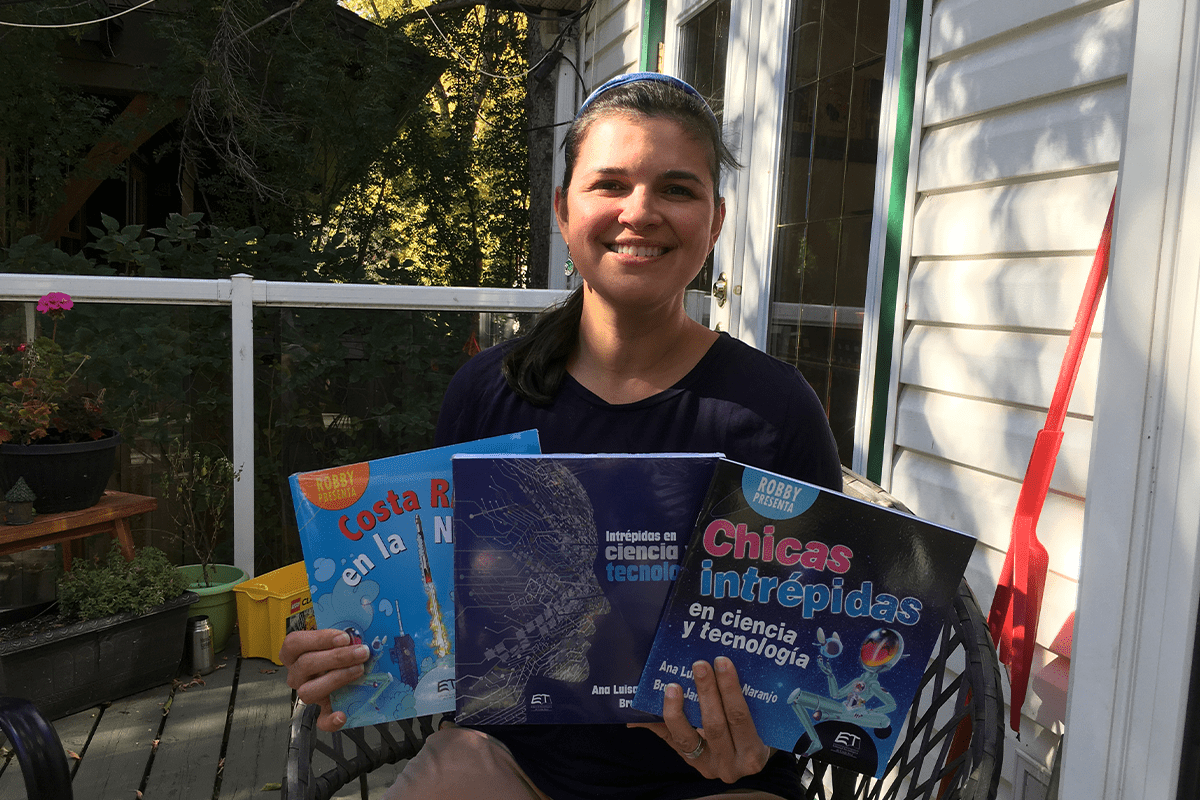

Together with Dr. Brett Finlay, she co-wrote the book “Let Them Eat Dirt”, a book aimed at parents, with valuable information on how to improve the health of babies and children. The book was translated into 14 languages and featured by the CBC, Good Morning America and the Wall Street Journal and was selected among Publishers Weekly’s Top 100 Books of 2016.

What are your hobbies and aspirations?

In addition to science, which I am passionate about every day, I dedicate my spare time to my family (husband and two children), to karate and to study French. I also really like historical novels. Among my dreams are to see my children grow and study, continue to lead research projects, train more young researchers, spread science more to the public, and hold positions of greater academic and scientific leadership. In the future I would like to get involved in science policy initiatives.

What did you have to sacrifice to achieve your professional goals?

Leaving Costa Rica and living in another country, which has been both a sacrifice and a benefit, because living in Canada and doing what I do here is a great experience, despite the fact that it involves missing my family members and other people close to me. In general, scientific work represents many hours of work and study and, without a doubt, spare time is sacrificed. However, it becomes more bearable when you dedicate yourself to what you are truly passionate about.

Who are your role models?

Many of my mentors throughout my career: Dr. José Bonilla, Dr. José María Gutiérrez, Dr. Karen Madsen, Dr. Jon Meddings and Dr. Brett Finlay. I have learned a lot from everyone. I also admire two world-renowned microbiologists: Doctors Bonnie Bassler and Margaret McFall-Ngai.

When and how did you realize that you wanted to study the field of microbiology, cell biology, and medicine?

I have liked science a lot since my childhood. I was interested in observing nature, conducting “experiments” at home, and reading. At school we were encouraged to be interested in research, since every year we had to do a research project that had a value of 5% for all subjects. Studying was not my favorite part of school, but I loved the research project.

At first, I thought I was going to study medicine, but just before choosing a career, I imagined myself in a laboratory and I liked the idea. It was at university that I also learned that I had to take pleasure in studying and reading a lot, and I still want to continue learning.

Tell us an anecdote from your childhood or adolescence related to the decision to study microbiology, cell biology, and medicine.

I remember very well when my dad took me to do a blood test in a clinical laboratory. He knew the microbiologist, and seeing that I was asking him questions about blood, he invited me to see the cells under a microscope. I still remember the images very vividly: the cells tinged with pink, blue and purple, their different shapes and sizes.

I spent a lot of time imagining what the cells did in the blood and how they “talked” to each other. It was no surprise to anyone when I decided to study microbiology.

What do you consider to have been the main achievements of your professional work and what are your aspirations for the future?

Having my own research group and its success is one of my greatest achievements. I am very proud to also give time and importance to communicate science to the general public. I have done this through many talks, articles, interviews, a book, a documentary and other plans on the way.

In the book Let The Eat Dirt I have had the opportunity to convey an important scientific message to thousands of people in 14 different languages. This scope is something that I would not have imagined when I began my journey as a scientist. In the future I hope to continue training new scientists and improve my ability to take science to as many places as possible.

Do you think that the contribution of women to the field of science and technology is different from that of men or not?

It is different, because there are fewer women in leadership positions in the sciences and there is a significant number of women scientists who do something other than science after their training.

Although there have been important advances in terms of equality between men and women, thanks to the invaluable contribution of pioneering scientists, being a woman continues to represent an important barrier, since women are professionally disadvantaged after having children and, even without having them, they lose opportunities in leadership, awards, financing, among other recognitions.

What initiatives, public or private, would you recommend to encourage female participation in science and technology?

There are good initiatives that promote that many women choose STEM careers (science, technology, engineering and mathematics). In fact, many careers have half or more than half women in their classrooms.

The problem, in my opinion, is not in encouraging more women to choose these careers, but rather manage to practice after studying, and when they do, they manage to overcome the barriers that limit professional advancement for them. The root of these barriers is merely social.

We continue to have a much higher burden for domestic reasons and for having children. Unless this changes, it will be difficult for such barriers to be reduced or removed. Such problems will take a long time to reduce, unless there are policies that directly limit them.

Other countries are succeeding with initiatives of this type, for example, by extending maternity leave that must be shared between mother and father equally and by promoting specific career opportunities for women, especially in their first year after becoming mothers.