Fifty-seven years ago in July was simply unforgettable. Sure, I was all of 6 years old, and had only just begun to have my surroundings indelibly imprinted into my future memory, but if you were around back then you must remember, too.

The skies were bluer than they’ve ever been since. The grass was huge and very green in the empty pastures that surrounded the old U.S. Embassy Residence. There were cows roaming the streets, and we all had cattle guards to keep them (mostly successfully) out of our homes.

It was a very special day. My family woke early and walked to the Embassy Residence for the picnic, which, as it is today, was held in the morning to avoid afternoon showers. It may have been the last time my Dad had to hoist me on his shoulders most of the way because I couldn’t keep up.

If I had been asked then where I would be living in 50 years, I would have wondered why I would be living anywhere but where I lived then – which, of course, is where I live now. A location obviously selected to be within walking distance of the picnic in San Rafael de Escazú.

The Embassy Residence was special to us for several reasons. One reason that stands out even more than the picnics themselves was that John F. Kennedy shook my brother’s hand at an event there two years before.

JFK had Costa Rica thoroughly smitten, and my brother was no exception: I don’t think he washed his hands for years afterwards. Of course, my mother later inadvertently threw out my brother’s diary where Mr. Kennedy wrote a note to his friend Michael.

Seen from the enlightened perspective of 2015, Costa Rica was a different world in 1965. It seems unreal to describe that world now. The country was embarking on its new path forward that had started in 1948. We were very isolated. We didn’t have U.S. fast-food chains. We couldn’t even buy ketchup.

My favorite birthday present was a small bottle of Welch’s grape juice, which to me was a fine wine. We didn’t have American TV, and movies arrived years after their original release. Transportation by horse out here in the boonies was still commonplace. Poisoned meat was still thrown in the streets by the authorities to control rabies.

All Americans spoke Spanish, very well, and most of our friends were Costa Rican; they welcomed us in their homes, as they were welcome in ours. We were assimilating. The 4th of July picnic was our one opportunity to parade Uncle Sam and the American flag and invite all our Tico friends to share our special day.

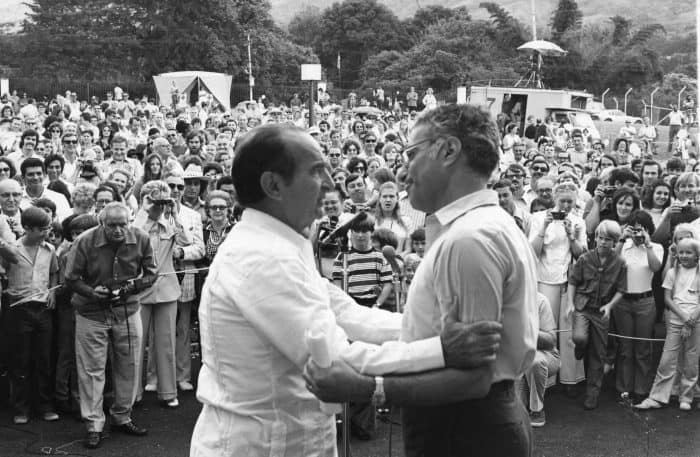

President José “Pepe” Figueres was a hero, not only to Costa Rica, but also to those of us who had adopted this country as well. The holiday was a time to hold hands and celebrate both our countries’ heritage, and vow to move together towards a better future.

Thanks to Jack Fendell, who started the American Colony’s July 4 picnic tradition, we continued to live our shared lives and our shared heritage. The picnic epitomized our two cultures learning to live, and grow, together.

There were relatively few American families in Costa Rica then, and we knew them all. In fact, it seemed to me that my parents knew everyone on the planet, but certainly everyone at the picnic, U.S. and Tico.

There was no visible security entering the picnic except for the very impressively outfitted Marines who couldn’t help playing with the kids. Everyone was welcome, regardless of nationality. No IDs were checked. It was a party for all.

July 4, 1965 was a Sunday, so nobody had an excuse to not come – if, that is, they could make it out to the hinterland of Escazú in the morning. I remember arriving vividly. The huge gates are wide open. The crisp Marines stand on either side and welcome you. You are immediately impressed with the fact that you’re walking towards the grandest house you’ve ever seen. It is immaculately white with huge columns around its entrance holding up a balcony.

There is an oval drive with a beautiful garden in the middle. It is mind-blowing. Surely even the real White House wishes it looked like this.

What a great day to be an American… in Costa Rica.

The ambassador and his family, who, of course, we and everybody else know, make a point of greeting us personally. The adults mingle, which means the kids are let loose to run around. Parents go get a drink (beer?), and walk around in their Sunday best laughing loudly, making us very glad to go and do all the kid stuff there is to do.

There are the games – three-legged races, sack races, egg tosses – the same theme there always was and always will be.

But I had two favorite events. I think we all agreed. You simply had to get on the oxcart that did continuous loops around the oval driveway, and you had to watch Woody Woodpecker.

As you can imagine, it was a beautifully painted, Sarchí-style oxcart led by two huge oxen. The concession to human cargo was rubber tires. The man in charge was our gardener’s cousin, and he swooped me up seamlessly into the insanity of too many other small children in the cart. Nothing much happened, and oxcarts were a common sight back then, but the fun of it was beyond description.

It was the Costa Rican version of a hayride, I suppose. You could stay on as long as you wanted, and boastfully wave to anyone you knew, which was everyone.

Then there was Woody Woodpecker. We didn’t have TVs at home. No cartoons, no Elmer Fudd, Mr. Ed or Bewitched. That was yet to come. But the embassy was special. They had a garage with a projector, an unstable screen, and more kids than could be accommodated in the folding chairs lined up for them, all screaming as the scratchy reel of endless black-and-white Woody cartoons started to show.

It was hot. We were all hungry and thirsty. It was loud. It was very, very fun. I can picture every corner of that garage. The rat-a-tat theme song rings in my ears as I remember it.

I also remember being told that the Secret Service had brought down the latest Woody cartoons just for us on a special plane.

Food was plentiful, and wonderfully unhealthy. As I recall, it was free, and all we had to do was run up to a stand and place our order, even when we couldn’t quite reach the counter.

Mrs. Jagush was in charge of hot dogs. But it was very Costa Rican too, because that’s what we were all used to and loved. There were sugar-encrusted churros, little plates of gallo pinto, gallos de chorizo, and tons of ice cream. It was like a Costa Rican feria, American style.

As the years went by, I never once missed a picnic. The residence was moved to where it is today a half mile down the road, where the picnic continued to be held for years until it began to be held at the Cervecería grounds. As the American population grew, the flavor of the party changed. In high school, years later, we arrived as usual and had fun as usual, lost every event as usual, and left before the rains came.

And we all, whether we admitted it or not, missed Woody Woodpecker.

This article first appeared in 2015