BOGOTÁ, Colombia – It was a cold January morning in 1986 when two Dutch journalists, Jan Thielen and Harry van der Aart, arrived at a cemetery in the south of Colombia’s capital city.

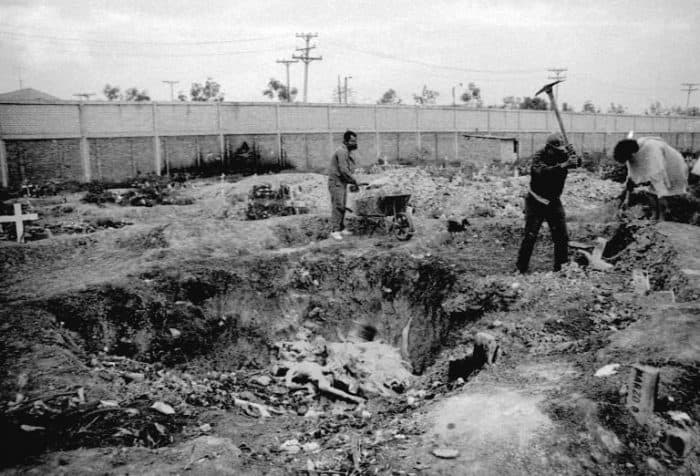

Tipped off about bodies being dumped there every Saturday, the two journalists hadn’t waited long when an old and dilapidated van drove into the cemetery. A few men stepped out and began unloading bodies. Some were bloated from being drowned, others were decomposing and a few had been burned. Some of the bodies had bullet wounds.

At one point, the journalists overheard the men say: “These are those sons of bitches from the palace.”

The bloodshed

Two months earlier, Colombia’s Justice Palace had been taken over by a group of 30 M-19 guerrillas who held lawyers, judges and Supreme Court justices hostage to demand then-President Belisario Betancur and his defense minister be put on trial for violating a peace treaty in the midst of Colombia’s bloody civil conflict, begun in the 1960s.

The government responded violently, using the army to regain control of the palace, resulting in the deaths of more than 100 people, including guerrillas, soldiers, civilians and Supreme Court justices. Eleven people – mostly cafeteria workers – went missing. Some of those victims had been seen leaving the building alive.

In late October of this year, the bodies of three of the 11 missing people finally were identified. The remains of Lucy Amparo Oviedo Bonilla were found in two boxes in a government warehouse, and those of Cristina del Pilar Guarín Cortés and Luz Mary Portela León were located in two separate common graves.

The photos the Dutch journalists had taken almost 30 years ago helped lead to the discovery of one of these graves. As a result, former army officials currently on trial now face additional accusations of torture against the cafeteria workers and visitors to the palace.

“So it was true,” Jan Thielen told The Tico Times during a phone conversation following the new revelations. “I’ve always known I had seen the missing people. But of course, I couldn’t be completely sure. So I only told what I had seen.”

Elusive truth

In the days after their visit to the cemetery, Thielen and Van der Aart spoke with human rights lawyer Eduardo Umaña Mendoza about what they had seen. They remained in Bogotá a few more days after that.

“I had an eerie feeling we were being followed,” Van der Aart recalled. “Already at the cemetery, there was someone intensely watching us.”

At the time, both journalists had to leave Colombia for other commitments: Van der Aart had been on a three-month photography trip and had to return to the Netherlands; Thielen had to get back to Buenos Aires, where he lived.

The two had taken these kinds of trips together before, combining traveling as friends with working as journalists. Their first trip was in 1979, after which Thielen decided to live in Bogotá before moving to Argentina in 1984. The two had expected the human rights lawyer to dig into the story, and they went on with their lives.

The M-19 demobilized in the late 1980s, with some of its former members eventually going into politics, including Gustavo Petro, who became mayor of Bogotá in 2012. But the mysteries surrounding the Colombia Justice Palace siege were never solved.

Thielen ended his journalism career to manage a guesthouse in Brazil, while Van der Aart remained in the Netherlands to pursue an art career. But the shocking images of that day in early 1986 have stayed with both of them throughout their lives.

Said Van der Aart: “It was very unexpected to see what we saw that day. It wasn’t the first time I saw dead people, as we had been reporting on the war in El Salvador. I had seen enough decapitated and tortured people there. But the shocking thing that day in Bogotá was the way the bodies had been dumped, as if they were garbage.”

In 2008, Thielen read an article in the Colombian magazine Semana and was shocked to learn that 11 people were still missing. Umaña, to whom they had told their story, had been killed in 1998, like so many other human rights defenders at the time. It seemed that Umaña had taken the story the Dutch journalists told him to his grave.

Thielen decided to contact journalist Ricardo Calderon of Semana and sent him the pictures. Although he was told a prosecutor might contact him to appear as a witness, it never happened. And it took a few more years for the remains finally to be identified. Now, 30 years after the Justice Palace siege, family members of three of the missing people finally know what happened to their loved ones.

“It is satisfying to hear about all of this,” Thielen said. “But it is also very difficult. I personally knew M-19 guerrillas and judges who died that day, so it is very difficult for me to think back about what happened.”

The anniversary

In a memorial service last Friday, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos apologized to the families of the missing for what happened that day in 1985. He also vowed to locate the remains of the other eight who are still missing.

Rafael Augusto Oviedo Bonilla, 60, brother of Lucy Amparo Oviedo Bonilla, whose remains were identified recently, attended the ceremony with his family. After viewing a painting of his sister, he told The Tico Times that the remains found were only three pieces of her spinal chord, like “caps of a soda bottle.”

Rafael Oviedo had always been certain his sister was murdered, and he had seen the video images of her leaving the building alive. To him, President Santos’ apology at the anniversary memorial fell short: “Belisio Betancourt is the real one to blame – it’s his apology we need to hear.”

Oviedo continued: “President Santos had to say what he did because last year the Inter-American Court of Human Rights condemned what happened. Still, the government will not lay down its weapons. That’s the problem with this country: Once a guerrilla leaves, another takes his place. Once a bad president leaves, another takes his seat.”

After the official ceremony, the memorial service turned into a festival, with rock music and hip-hop laced with lyrics about those who are still missing. In the evening, a video compilation of the tanks and the firefights were projected onto the new palace, rebuilt after the siege.

‘Narcos’

A popular Netflix television series about Pablo Escobar called “Narcos” portrays as fact that Escobar financed and planned the Justice Palace siege to destroy incriminating evidence against his drug cartel to avoid extradition to the United States. But there is little evidence to prove that Escobar actually paid $1 million dollars to the M-19, and according to Thielen, the link between Escobar and M-19 doesn’t make sense.

“Anyone who knows anything about the history of Colombia knows these two would never work together,” Thielen said.

“Americans like to look at Colombia in a very simplistic way: M-19 was a guerrilla group, so they were communists, and therefore they were bad and would join forces with any criminal in the country,” he added. “It’s not that simple. The members of M-19 weren’t communists, and they would surely never work with Escobar.”

Recommended: After 23 years in prison, top assassin for Pablo Escobar is a ‘reformed’ man