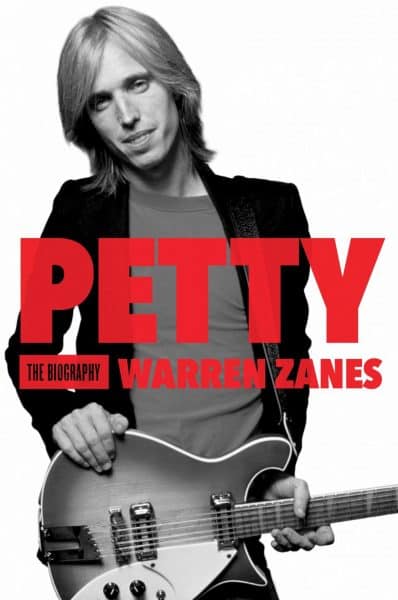

The idea for a new unauthorized Tom Petty biography came from a surprising source: Tom Petty.

“He didn’t want it to be authorized because he felt like authorized meant bull—-,” says Warren Zanes, whose “Petty: The Biography” arrives next month. “He said, ‘I want it to be yours. And I can’t tell you what you can and can’t write.'”

The result is a penetrating profile in which Petty opens up for the first time about his heroin addiction, something he had sliced out of Peter Bogdanovich’s four-hour documentary, 2007’s “Runnin’ Down a Dream.” Zanes also coaxed Stan Lynch, the ex-drummer of Petty’s longtime backing band, The Heartbreakers, to talk unflinchingly about his falling-out with Petty.

And there’s plenty more as Zanes, granted full access, reports on the creation of not just Petty’s biggest records, “Damn the Torpedoes,” and “Full Moon Fever,” but his less appreciated gems, including 1999’s “Echo.” Zanes is more than a fan: In 1987, his band, the Del Fuegos, opened gigs for their hero. Years later, Petty, fascinated by the Dusty Springfield book Zanes wrote, invited him to dinner and rekindled their friendship.

Zanes spoke by telephone about “Petty.”

Q: Let’s get right to this. In a world of headlines, this is going to be a big one. I told my editor about Petty’s heroin addiction in the ’90s. She said, ‘How does a 50-year-old become a junkie?’

A: That happens when the pain becomes too much and you live in a world, in a culture, where people have reached in the direction of heroin to stop the pain. He’s a rock ‘n’ roller. He had had encounters with people who did heroin, and he hit a point in his life when he did not know what to do with the pain he was feeling.

Q: And he hasn’t ever spoke about this before.

A: The first thing he says to me is “I am very concerned that talking about this is putting a bad example out there for young people. If anyone is going to think heroin is an option because they know my story of using heroin, I can’t do this.” And I just had to work with him and say, “I think you’re going to come off as a cautionary tale rather than a romantic tale.” But again, this is important to show that Tom Petty is a man who lived the bulk of his life in the album cycle. He wrote songs, they recorded those songs, they put a record together with artwork, they released it, and they went out on the road to support it. Over and over and over and over and over. And he, being the leader of the band, had to do most of the work around it. I think he was invested in being caught up in that cycle but there was so much movement that the trouble from his past was kept at bay. And when he left his marriage and moved into a house, by himself, things slowed just long enough that all of that past came right as he’s coming into the pain of not being able to control the well-being of his kids and not being able to control a dialogue with his ex-wife. The classic situation of midlife pinning a person down to the mat.

Q: The other obvious question. Heartbreakers’ (bassist) Howie Epstein was cut loose because of his heroin addiction. And he died soon after. Petty’s also addicted, and he gets to work his way out of his. It there something hypocritical about it?

A: Here’s the important point. The Heartbreakers sent Howie to rehab. They tried to help him, and the last tour that they had Howie on, in the days prior to the tour, he was stopped by police in a stolen car with Carlene Carter with black tar heroin. And he was still on that tour. The Heartbreakers are hardly a case study in intolerance. They held on trying to keep that band together. That’s kind of the Heartbreakers code. You keep this band together. But it got untenable.

Q: I’m intrigued by your place in this story. You first encounter Petty as a fan and then, you’re in this rock band, the Del Fuegos, and opening up for these guys.

A: We grew up loving Tom Petty more than his contemporaries. Many of whom we had strong feelings for. From Bruce Springsteen to Graham Parker to Elvis Costello. But Petty was always just the right fit, for me, my brother, my sister and my mother. Petty was our guy. When a Tom Petty record came out, it was an event.

Q: Flash forward to the 1980s. You’re at Petty’s house at a Christmas party. You have left the Del Fuegos. You stumble upon George Harrison, Jeff Lynne and Petty in Petty’s office, jamming. Basically, you’re witnessing the birth of the Traveling Wilburys.

A: I went and I gave Tom and his family a copy of an Ann Peebles record. They got me a Beatles magazine from 1965, the year I was born. Then you’re at this party and you hear rumblings that George Harrison is in the building. The presence of a Beatle is a thick presence. I went to Tom’s then-wife, Jane, and said, “I’m not an autograph guy but we’re talking about a Beatle.” And she grabbed me, brought me through this hallway and into this door opening into Tom’s office. And then kind of pushed me in. I’m suddenly in this room holding a magazine. I was wearing this brocade jacket and had long, bushy blonde hair. They’re all playing and they all stop because this kid ran into the room with this Beatles magazine. And George Harrison looks at me and says, “It’s Brian Jones, back from the dead.” And George knows enough what a man who wants an autograph looks like. George takes a Sharpie and signs it for me for every Beatle and hands it back to me.

Q: This is the birth of the Wilburys.

A: It’s a moment where these guys, no matter how corny it might sound, they were kind of falling in love with each other. I think it’s different at that altitude. We have a freedom to walk down the street and meet people. Guys at that level of success, I think they meet fewer people where they think, this could be a friendship. And when it happens, it’s certainly a big deal. And certainly in Petty’s life, it was a big deal when he and George Harrison came together … In retrospect, I look back at that scene, in that office, and I think that maybe it’s the happiest I’ve seen Tom Petty by looking at his face.

Q: Stan Lynch. We know him as a vital member of the classic Heartbreakers lineup. But he’s never really opened up about his split with Petty and the band.

A: Stan said no to the interview between three and four times. And he did it very respectfully. I reintroduced myself. He remembered me from the tours. He referred to the band as the Del Tacos. He, in his own way, said, I just don’t want to go back there. I could have moved forward without him. And I was poised to do that. But the last time I tried, I don’t know if he was in a better spot, I reduced it to, “Stan, I will fly down there, rent a car, come to your door for 20 minutes. And at the end of 20 minutes, if you tell me to leave, I will leave. I promise you.”… That 20 minutes turned into two days and eight hours. And at the beginning of that second day, it began with, “Do you mind if I lie on the couch.” I was lucky enough to be the guy taping it when he let a lot of that stuff out. When he released that safety valve out. It really came out very intense, at times remorseful, at times angry but he helped the book immeasurably. Because he is the lone extrovert in this band of introverts. Petty’s got a very strong voice but I needed the foil.

Q: Let’s get back to the ground rules for this book. You were open to doing an authorized version, right?

A: Yes. But he said, “It’s your book. Your contract. I can’t tell you what’s in it or not in it.” Here’s what he’s acknowledging: that a warts-and-all portrait doesn’t throw you into the gutter. You can actually remain on the pedestal that you’ve earned as an artist. We don’t mind our heroes to be human. That’s a hard thing to arrive at. But I think these guys have arrived at it because they’ve had their own experiences with books that portray their own heroes as humans.

Q: As a fan, I have to grumble that Petty’s never been given quite the same level of respect as, say, Bruce Springsteen. I favor Petty.

A: A couple things. Tom Petty has had too many hits for critics to be fully comfortable with him. The old, art commerce divide where people go, “Oh, it’s too commercial.” The other thing, I was just talking to somebody who was watching a live Tom Petty concert on a computer, no between-song banter. He didn’t ever get a trampoline out and do a backflip. No, he goes out and plays the songs that he wrote. That extends to interviews. He’s just not a self-promoter. He couldn’t go from music into politics, and Bruce could. And that’s not a judgment on Bruce. There are times I wish that Petty was more of a self-promoter if only so that his songs could travel a little more widely. Because they’re so good.

Q: I keep going back to this band and I can’t help but feel like the reason the Heartbreakers won’t die, can’t die, is because Petty’s family was so dysfunctional. His father beats him. His aunt hounds him for autographs at funerals. He basically has no connection to that family back in Florida.

A: When he gets into a rock band, that’s like the second chance to have a family. It’s not just because you need the band to make the music. It’s because he’s trying to succeed at something that his own family failed at dramatically. When he gets married, it’s the same thing. He tells us the story of a marriage that isn’t working, but he’s trying as hard as he can to keep it together. So that guy who is hellbent on keeping things together, because that is who he is, keeps his band together. By virtue of his band staying together and the quality of the musicians, the Heartbreakers are a singular story in popular music.

© 2015, The Washington Post