Compared to Renaissance greats like Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer is a B-list celebrity. The name “Dürer” doesn’t have the same romantic ring as “Botticelli.” He was German, not Italian. And he is most famous as an engraver, a medium that seems flatter and less colorful than painting. Everybody fawns over “Mona Lisa,” traveling thousands of miles to ogle its microscopic strokes; far fewer have heard of “St. Jerome in His Study,” a black-and-white portrait of a guy sitting in a room.

Yet the new exhibit at the Central Bank Museums is a startling opportunity to see Dürer’s work, and everyone within a 300-kilometer radius of the Plaza de la Cultura should see it. Its Spanish title is “Durero: Genio del Renacimiento,” and the one-room exhibit does a commendable job proving that Dürer was a “Renaissance genius.”

Printing presses now seem like antiquated technology, but when Albrecht Dürer was born in 1471, the very concept of movable type was only about 35 years old. Johannes Gutenberg’s invention was the super-computer of its age: instead of copying entire books by hand in lonely scriptoria, printers could carve a single block or plate and print as many copies as they wanted. Dürer saw the possibilities of printing at an early age, and he helped define the art form for centuries to come.

Dürer grew up in an affluent family in Nuremberg and spent a lot of his time wandering around Europe. He learned so much about art, geometry, and mathematics that he ended up writing respected treatises about them. Like his Italian peers, Dürer was more than an imaginative doodler; he helped Europeans advance their understanding of the world, and he won the respect of both academics and royal courts. His signature is widely considered the first real “trademark.”

You may wonder why a Dürer exhibit would be significant to Costa Rica. After all, what influence did a 16th-century German draughtsman have on modern Latin America? The first Spanish colony was built in Costa Rica in 1524. Four years after that, Dürer died. The Venn-diagram overlap between Dürer’s life and Costa Rica’s history is all but nonexistent. The art and architecture of Costa Rica owes most of its existence to the Iberian aesthetic. Wouldn’t any other artist be as meaningful? Why Dürer?

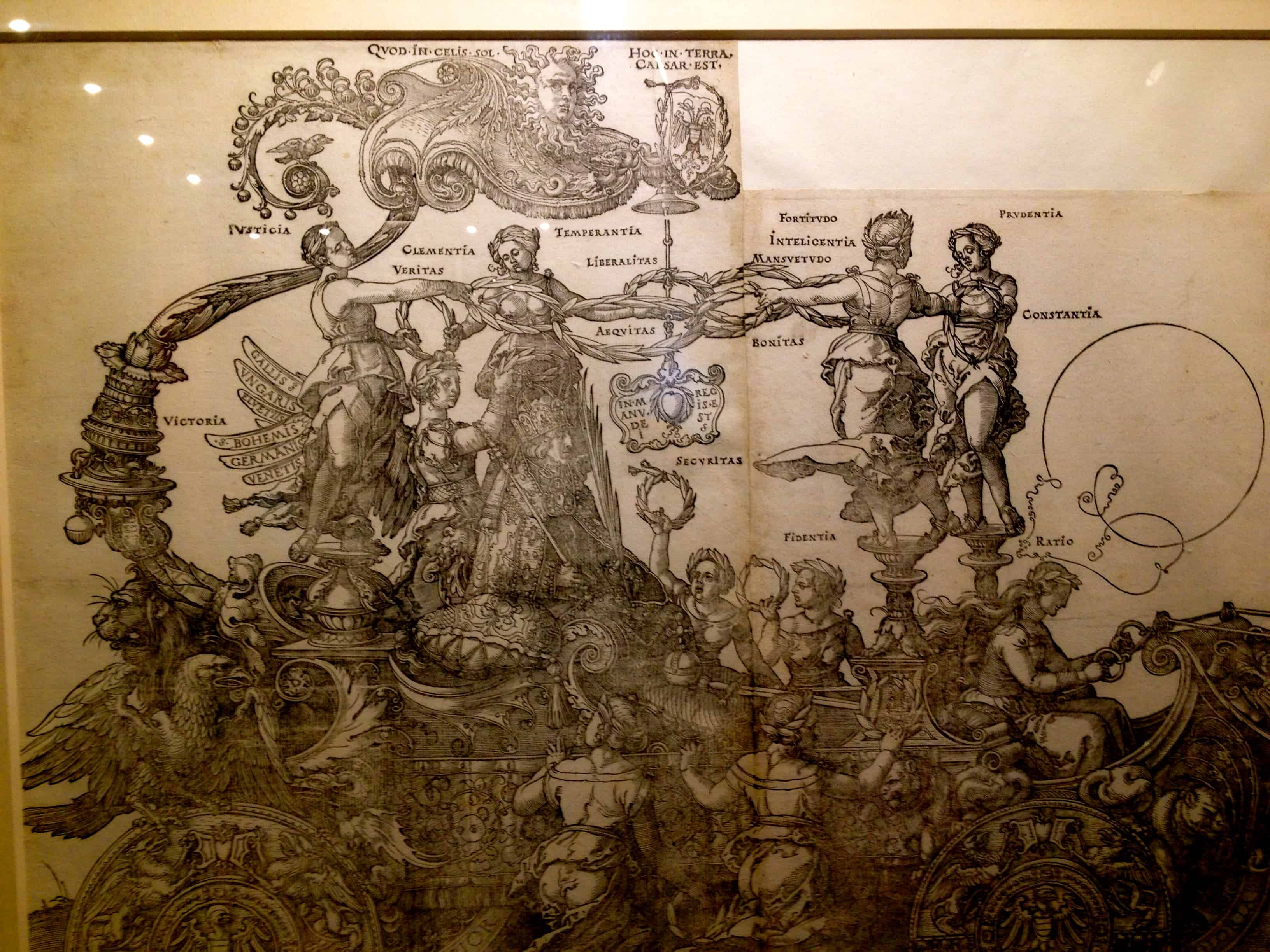

Well, why not Dürer? The Central Bank Museums have received a magnificent collection of Dürer prints, which are arranged in roughly chronological order, and it is astonishing to see how a devout young man gradually mastered texture and perspective. His early prints seem medieval, both in subject and style, the kind of blasé New Testament scenes you might see in a Book of Hours. But as he grew older, Dürer gave his characters extremely complex physical features – elaborate faces and musculature – that make his style instantly recognizable centuries later. Even if you’re not familiar with Dürer’s name or biography, you have likely seen his “Rhinoceros,” a distinctly European attempt to depict the Indian animal, even though Dürer never saw one in real life. All his characters seem heavy and aged. Unlike the Italians, Dürer preferred the nuances of human imperfection to bland beauty. Even his “Adam and Eve” look plain and sinewy, not the fresh-faced innocents of cheerier artists.

The museum staff has done a commendable job of explaining Dürer’s accomplishments, and despite some cringe-worthy English translations, the bilingual placards are a welcome addition. Dürer is not easy to appreciate, and unless you have a degree in Medieval and Renaissance Studies (as this critic does), you may not “geek out” the moment you step into the museum’s subterranean gallery. Even the most devoted art student may find the endless biblical images tedious. The explanatory print helps give these portraits context.

But here’s the best part: Dürer’s work is often associated with the occult, and if you have even a passing interest in “The Da Vinci Code,” you will see similar cryptic patterns in Dürer’s work. The exhibit includes a copy of his masterpiece, “Melencolia I,” one of the most mysterious engravings ever pressed into paper, and “Knight, Death, and the Devil,” which is just as ominous today as it was in 1513. In these two prints alone, you’ll see a reclining dog, a monstrous Lucifer, a scowling skull, a distant castle, an overturned hourglass, a compass, a creepy-looking cherub, uneven scales, a carpenter’s plane, a distant city, a distant castle, a distant sea, a second hourglass, another reclining dog, and finally a mind-bending “magic square” whose meaning has eluded scholars for 500 years. And if that doesn’t make your spine tingle, note the giant, perfect sphere positioned in the lower left. Look familiar?

Whether you see the “Alberto Durero” exhibit for the sake of art history or to unlock the secrets of the Illuminati – or ancient aliens, or whatever – the series is well worth seeing. Dürer’s work may not have the cachet of the Sistine Chapel, but take a closer look. There’s a lot to see.

“Alberto Durero: Genio del Renacimiento” displays through April 26 at the Central Bank Museums, downtown San José. Daily, 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. ₡5,500 ($11). Info: Museum website.