The worries for Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva seem to have no end. On March 3, a newsmagazine published what it said were accusations by a onetime political ally, including that the former Brazilian president, known as Lula, had orchestrated a plot to buy off a witness in the giant corruption case at state-run oil company Petrobras. The next day, federal police detained and interrogated Lula on suspicion that he’d benefited from the Petrobras scheme. And now, in a separate case, São Paulo prosecutors are seeking Lula’s arrest on charges of money laundering and false declarations; if a judge decides to send him to trial, Lula could face up to 13 years in jail.

Why all the fuss over a septuagenarian ex-president? Sure, the charges are a slap to a leader who charmed heads of state, hoisted his country to international prominence and left office with a rock-star approval rating. But more than a legend, Lula is still revered in Brazil as a shrewd deal-maker, whose sway over the ruling leftist Workers’ Party is key to the survival not only of beleaguered President Dilma Rousseff but also of the ambitious political project Lula launched to remake the country 13 years ago. If Brazil’s heralded new generation of cops and sleuths fails to curb its excesses, they stand to lose the crucial battle for public opinion. And the small revolution they started to root out powerful crooks could be in jeopardy.

Don’t count Brazil’s political tag team out yet. Rousseff is facing an impeachment drive in Congress, and her foes will demand her ouster in street demonstrations Sunday. But she has yet to be charged with a crime, and the allegations against Lula must stand up in court. For that, investigators will need time and flawless detective work but also discernment and temperance, qualities that look to be in short supply at this fevered political moment.

For the past two years, the so-called Car Wash case probing corruption at Petrobras has been a model of even-handed investigative rigor. A team of dedicated federal prosecutors and police has conducted 1,114 inquiries, carried out 133 arrests and is pursuing $4 billion in stolen assets, with care and little drama. Sergio Moro, the federal judge presiding over the cases, has been discreet, even when bringing down giants. The public has responded positively, and Moro’s supporters have practically beatified him. But the recent tumult suggests that some of the glory may have gone to the avengers’ heads.

See: ‘Historic’ crowds protest against Brazil President Dilma Rousseff

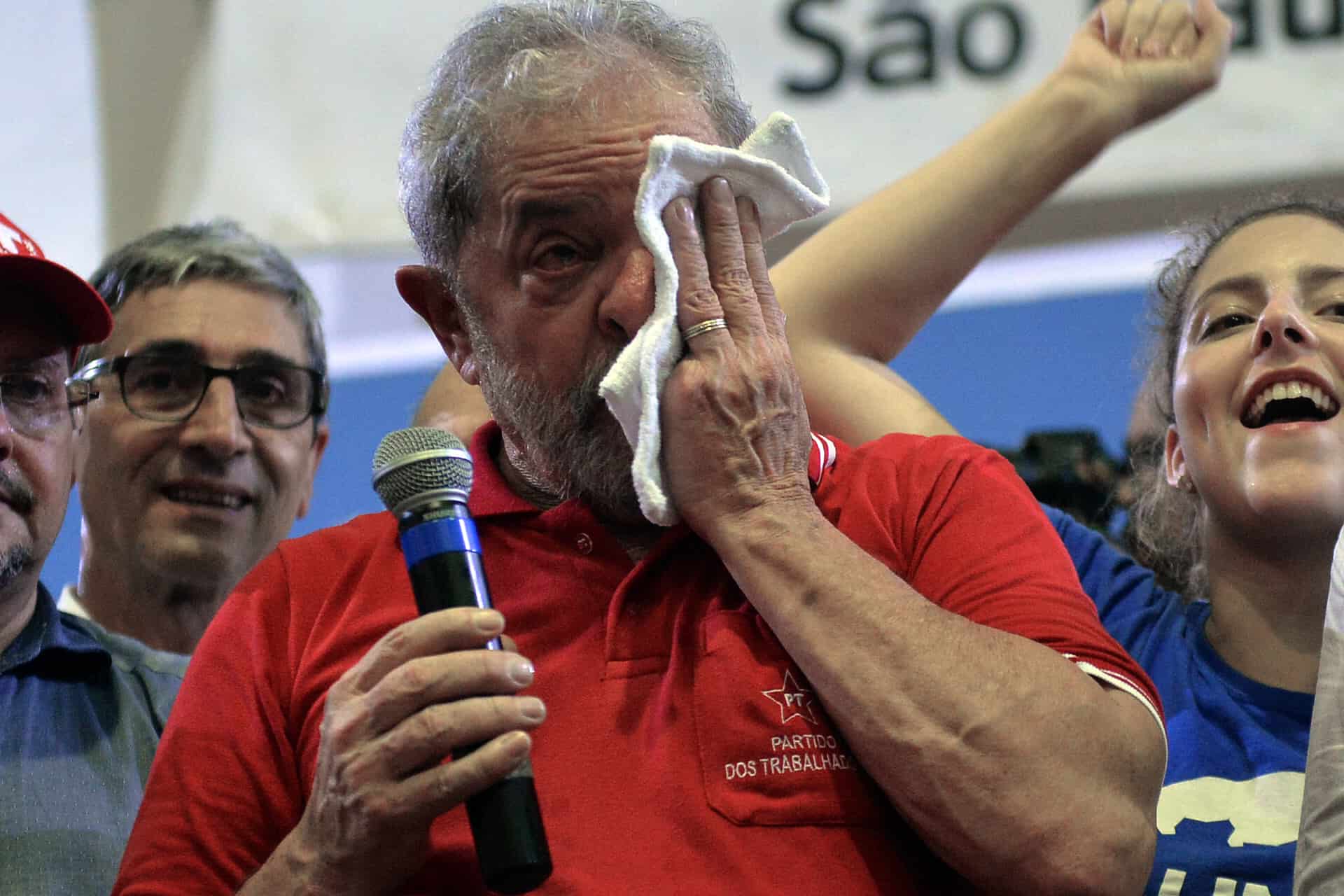

Lula’s detention by the police — not quite an arrest, but more than a summons — was a jolt. When police showed up at his door on the morning of March 4, the former leader apparently said he would only leave in handcuffs, although he agreed to go after talking to his lawyer. The public reacted strongly, with angry supporters rushing to Lula’s defense, likening his detention to a coup and scuffling with anti-Lula protestors.

The effect was to cast Lula as a political detainee of a state captured by “retrogade economic elites,” in the words of one loyalist governor. (The irony, of course, is that Lula is in trouble largely because of his perhaps too cozy relations with some of the country’s elites.) Lula emerged from his interrogation “more or less like Nelson Mandela left prison in South Africa,” as one columnist put it. That’s a role that the former steelworker who was persecuted and jailed under Brazil’s military dictatorship knows how to play well.

Brazil’s economy may be slipping from recession to outright depression, but to many poor and blue-collar Brazilians, Lula is still a hero. Moro knows the risks of taking on the big shots. He warned of them in a 2004 paper on how Italian prosecutors and judges in the Clean Hands operation broke up a cabal of crooked companies and their seemingly untouchable sponsors in high office. Being right and diligent is essential but not enough: In a porous justice system and a culture of complacency, “The corrupt politician, for example, has comparative advantages,” Moro wrote. The way to even the score is to take the argument public: “Informed public opinion, expressed through appropriate channels, is what it takes to attack the structural causes of corruption.”

It’s too soon to know who will win the argument in Brazil. In many ways, the widening Car Wash case is driving national politics, with every new bust or raid putting government on the defensive, undermining consensus on crucial policies to right the economy and inflaming partisan passions. It’s no exaggeration to say that both Rousseff’s political survival and the fight to stamp out Brazilian corruption are at stake. The country’s prosecutors have done their part, albeit sometimes to a fault. On Sunday, we’ll get a sense of whether they’ve gone too far, or not nearly far enough.

Mac Margolis is a Bloomberg View contributor based in Rio de Janeiro. For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit http://www.bloomberg.com/view.