The U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination wants Costa Rica to remove the controversial book ‘Cocorí’ from classrooms, among other suggested measures to combat racial discrimination. The request to stop teaching the book, which until recently was part of the curriculum in Costa Rica’s grade schools, was made Friday at the end of a nearly monthlong meeting of the U.N. committee.

In a statement, committee members also noted their concern about “racist insults and threats” against Afro-Caribbean lawmakers who have fought against official glorification of what they say is an insulting and discriminatory text.

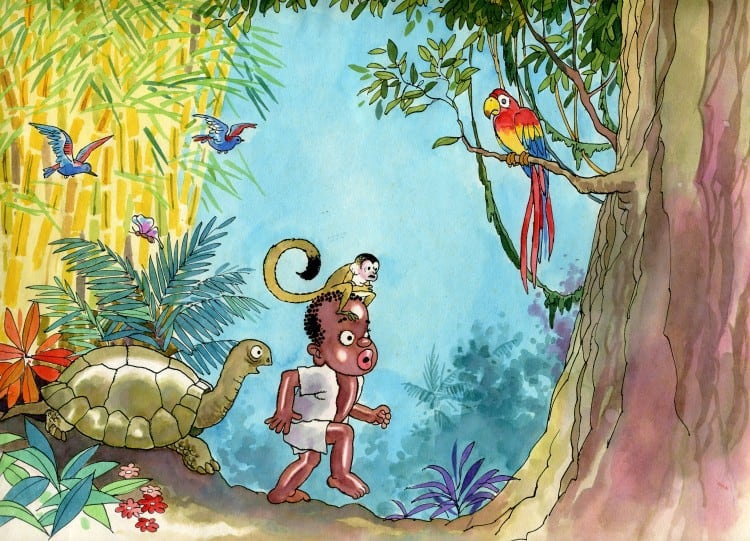

“Cocorí” is a well-known but polemical children’s book written by the late Joaquín Gutiérrez about a young black boy who falls in love with a blonde girl. It’s content — and popular illustrations of it — incite heated debates in a country that still struggles with a history of discrimination against citizens who are Afro-Caribbean descendants.

In May, congresswomen Epsy Campbell and Maureen Clarke, both of Afro-Caribbean descent, filed complaints with the government ombudsman’s office after receiving a wave of racist threats in person and on social media. The lawmakers had asked the Culture Ministry to withdraw funding for a musical adaptation of Cocorí.

Campbell, of the ruling Citizen Action Party, said she had received numerous racial insults on social media, including calls for her to “go back to Africa.”

Also recommended: ‘Cocorí,’ a racism debate, and a brief history of controversial children’s lit

The U.N. committee’s report asks Costa Rica “to make sure that textbooks with a racist connotation are withdrawn from the syllabus in elementary schools.” The committee’s 18 independent experts said they worried about the use of school texts that can “be interpreted as having a stereotypical vision of minorities, especially of indigenous or Afro-Caribbean populations.” They asked the Costa Rican government to honor “the knowledge of the Afro-Caribbean and indigenous populations’ cultural practices and their contributions to Costa Rican history and culture.”

The committee, which is charged with evaluating member countries’ compliance with the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, also expressed worry over the existence of “internal regulations in various schools” that “deny Afro-Caribbean persons from their cultural identity.” And it asked Costa Rica to pass a law that would reform its criminal code to include harsher sentences for racially-motivated crimes.

But the country has made strides — some of them recognized by the U.N. committee — towards embracing its diversity.

In July, the Ministry of Public Education ordered the director of a high school in Escazú to cancel a policy that prohibited students from wearing their hair in dreadlocks. Education Minister Sonia Marta Mora told the news site Amelia Rueda that dreads were part of Afro-Caribbean identity and therefore were a fundamental right.

This week President Luis Guillermo Solís signed a bill into law reforming the first article of the Costa Rican Constitution to redefine the country as a “multi-ethnic, pluri-national nation.”

The U.N. committee looked positively on the constitutional reform, along with the adoption of a national policy to fight racism, xenophobia and racial discrimination, and the creation of a Commission for Afro-Descendent Affairs.

The report also asked Costa Rica to ensure dignified workplaces and to pay attention to “judicial and social exclusion” and “specific vulnerability of migrant indigenous people temporarily occupying coffee plantations and the situation of women migrants employed as domestic workers.”

Costa Rica’s Ombudsman’s Office released a statement Friday afternoon supporting the report’s findings. The office highlighted the committee’s recommendations to include an option for people to self-identify their ethnicity on official surveys and data collection.

With information from AFP