GUATEMALA CITY – Even after the country came to a standstill on Thursday and an estimated 100,000 people filled Guatemala City’s main square demanding his immediate resignation, embattled President Otto Pérez Molina clings to power and refuses to step down.

Students from the state-funded University of San Carlos joined students from private universities, women’s organizations, peasant groups and ordinary citizens in an unprecedented show of unity. Over 100 retailers remained closed so their employees could take part in the nationwide paro nacional, or national strike, despite the fact that Guatemala’s influential business lobby, CACIF, didn’t officially join the protest.

The strike took place a week after the U.N.-supported International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) and the Public Prosecutor’s Office presented key evidence of Pérez Molina’s involvement in a massive customs fraud ring known as “La Línea,” including wiretap recordings in which the president insists on the appointment of customs officials who played a key role in that network.

In the midst of heavy rain that began pelting down soon after midday, protesters marched on, undeterred, with ink smeared across their homemade placards.

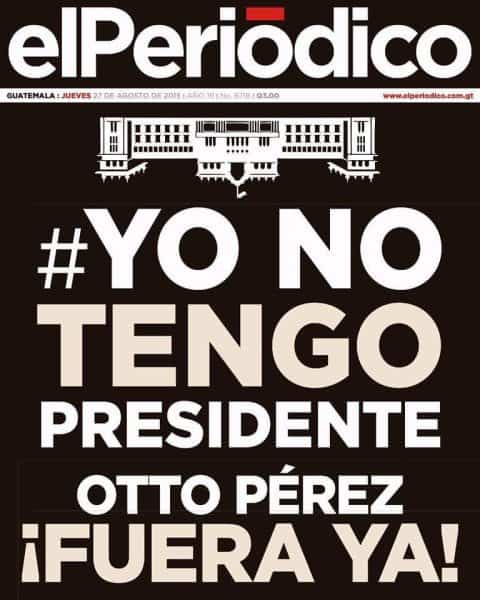

The daily El Periódico made the #YoNoTengoPresidente – “I don’t have a president” – hashtag that has gone viral since Wednesday its front-page headline on a black background, with the image of the presidential palace turned upside down.

Adding to the pressure, the Comptroller General’s Office joined the unanimous call for the president’s resignation.

For the second time in three months, Pérez Molina is facing impeachment proceedings in Congress, although an alliance between his Patriot Party and the Lider opposition party is preventing that from currently moving forward.

Like father, like son

In a parallel scandal, President Pérez Molina’s son, Otto Pérez Leal, who is seeking re-election as mayor of the large Guatemala City suburb of Mixco, also is facing corruption charges for alleged mismanagement of municipal funds.

Yet in an interview with Radio Sonora, the president reiterated a message he conveyed in a pre-recorded televised address to the nation last Sunday, insisting he is innocent of wrongdoing and stating that he will not resign before he leaves office in January.

“The worst you can do is believe the rumors that I’ve resigned, that I fled the country or that I’m hiding,” Pérez Molina told Radio Sonora. “That’s not the way I am, that’s not in my character and I’m going to face this.”

The president of Guatemala has not appeared in public since last Friday, fueling rumors that he intended to leave the country. In response, a group of activists filed a habeas corpus petition to ascertain whether he was still in the country.

On Thursday, former Interior Minister Mauricio López Bonilla and former Defense Minister Manuel López Ambrosio, who are under investigation for their alleged involvement in La Línea, were photographed by fellow passengers as they boarded flights to the Dominican Republic and Panama, respectively.

Said Pérez Molina: “To all those who protested today, I respect their right to do that. I respect their freedom and their constitutional right to voice their demands. They can ask me to resign, but that’s my decision to make.”

Watch a video of Thursday’s demonstration courtesy of Quetzalvision. The song’s lyrics state, “We’re fed up with so much corruption. … We want prison for all those who are corrupt.”:

The president’s billionaire friend

A recent article published by independent news website Nómada attempts to explain the president’s steadfast determination to cling to power in the face of widespread calls for his resignation from all sectors of society, including CACIF.

Nómada’s director, Martín Rodríguez Pellecer, asserts that a day before Pérez Molina delivered his defiant televised address to the nation, he was considering stepping down. Before doing so, Nómada reports, he made a crucial telephone call to the country’s most powerful telecommunications tycoon, Mario López Estrada.

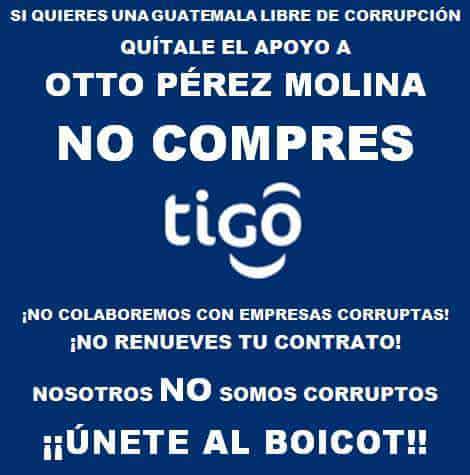

López Estrada, the only Guatemalan to be featured on Forbes magazine’s billionaire list, controls Comcel (Tigo), which controls about half of the country’s mobile phone market.

According to Rodríguez, López Estrada, who does not belong to CACIF, agreed to throw the sinking president a lifejacket in exchange for exclusive access to the 4G market for which his competitors, including Carlos Slim’s América Móvil and Spanish giant Telefónica, are vying.

Following the resignation of seven of Pérez Molina’s Cabinet ministers last week – a total of 14 Cabinet members have resigned so far – the president appointed Acisclo Valladares Urruela, who until a week ago was Tigo’s CEO, as director of the National Program for Competitiveness. He also appointed Ricardo Sagastume, the former president of the telecommunications chamber – whose only member is Tigo – as economy minister.

Pérez Molina’s relationship with López Estrada, Rodríguez notes, dates back to 2010 when he obtained crucial support from the Lider and Patriot parties to block the creation of a new tax on telecommunications.

López Estrada “is the most powerful actor that could have supported [Pérez Molina] at the moment,” Rodríguez told The Tico Times. “That’s why [Pérez Molina] refuses to step down and is being so confrontational.”

These revelations have led to angry reactions by protesters, with many calling for a boycott of Tigo products.

Roberto Wagner, an international relations professor at the Francisco Marroquín University in Guatemala City, believes that no matter how powerful López Estrada may be, his support on its own will not be enough to allow the president to remain in office until his successor is inaugurated in January 2016.

“I think the situation is unsustainable. Five months is a long time to remain in power,” Wagner told The Tico Times. Wagner believes a decisive factor that will determine Pérez Molina’s future will be his ability to negotiate with leading opposition candidates, such as Manuel Baldizón of the Lider party. It is Pérez Molina’s successor, Wagner noted, who will have the power to prosecute the current president on corruption charges.

Bipolar US policy?

Another key factor that could explain President Pérez Molina’s determination to weather out the political storm is the U.S. Embassy’s alleged reluctance to see him removed over fears that it could destabilize the country and jeopardize U.S. business interests.

On Aug. 26, The New York Times ran an editorial arguing that Pérez Molina is “delaying the inevitable” and should step down, which shows the U.S. is keeping a watchful eye on Guatemala’s political crisis.

The United States is one of the main donor countries supporting CICIG, which uncovered the La Línea scandal and a separate money laundering operation involving the country’s main opposition party, Lider. The U.S. government also exerted considerable pressure on the Pérez Molina administration to renew CICIG’s mandate last April.

Rumors that the U.S. intends to request the extradition of former Vice President Roxana Baldetti, who was charged with corruption for her involvement in La Línea, have intensified in recent weeks.

U.S. Ambassador Todd Robinson has been supportive of Guatemala’s anti-corruption protests. However, he also has been perceived as supportive of allowing Pérez Molina to remain in office.

“Unfortunately, with its lack of clarity, the U.S. has sent contradictory messages to Guatemalan society as well as the international community,” political analyst Christhians Castillo told The Tico Times.

Those apparent contradictions have outraged protesters. On July 6, Robinson was pushed and booed by angry protesters when he attempted to join a demonstration outside the Guatemalan Congress. During a demonstration on Aug. 15, protesters set fire to a U.S. flag with the message “Todd go home” written in black spray paint.

“The U.S. is upholding its own interests – the war on drugs and stemming the tide of Central American migrants to the U.S.,” Wagner said. “On the other hand, the U.S. has always been terrified of revolutions. When you look at the region as a whole, Honduras is also suffering a huge political crisis, and El Salvador faces a huge security crisis, so there’s a risk that Central America’s Northern Triangle could spiral out of control.”