Cytomax! Mark Lyons’ heart sank when he saw the empty black and orange packet of energy drink mix he had choked down the day before in a desperate attempt to provide his wasted muscles with a modicum of energy. He had just spent the better part of the day laboring up, across and down a steep, vine-covered hillside only to end up in the same place he started the day before – with no shoes, and no food – by a river, in the middle of a Costa Rican jungle. By then, it had been more than 24 hours since the slip; since he went missing.

Normally a strict observer of “leave no trace” wilderness ethics, Mark had left the energy drink packet on the rock in case someone looking for him came across it. He stared down at his ravaged feet, feeling a little depressed. The two thin pairs of cycling socks he still had on were certainly better than nothing, but nevertheless a pathetic match for the thick, spiny vegetation of Carara National Park.

Poisonous spiders, venomous snakes and other potentially ruinous creatures? Mark had barely thought about them. Nor did he know that “Carara” means “river of alligators” in the Huetar indigenous language. “Ignorance is bliss,” he would later say. Earlier in the day, Mark had found some giant leaves, which he wrapped around his feet to make primitive sandals. He used skinny vines like twine to tie the leaves in place, but it didn’t work. They came off after less than 20 steps.

So he went back to trekking through the jungle in his cycling socks, until he came to the rock with the Cytomax wrapper still sitting on top of it, like a bad omen. But Mark is not a guy easily prone to feelings of helplessness. He’s a burly, Colorado mountain man – albeit one with kind, blue eyes and an easy smile. He has chased bears out of his garage. He’s an extreme mountain biker. And he’s a father of two girls whom he frequently drilled on wilderness survival skills when they were growing up.

He just had to get back to that road, he kept telling himself. Mark had been riding on “that road” the previous morning, Nov. 5, the first day of the Ruta de los Conquistadores Mountain bike race from Costa Rica’s Pacific to Atlantic coasts. The three-day race is known as one of the hardest adventure competitions in the world, and Mark had come to ride it for the first time with a group of cycling friends from the Denver area.

But then he slipped and embarked on a very different adventure, one that almost cost him his life. Sitting by the river, Mark noticed that just upstream from the rock where he had eaten the energy drink powder the previous day, two rivers merged. Whitewater cascaded down the one furthest from him. Despite his initial dejection at seeing that Cytomax packet, he would later realize it might have saved him. Mark had been following the wrong river.

He figured he had to get to the opposite bank and follow the whitewater river upstream. That’s where he thought he’d find the road. The water in front of him was fairly calm and looked crossable, though after the previous day’s ordeal, he would’ve preferred an even calmer, shallower spot. He didn’t see one, so he gingerly stepped out into the waist-deep river. He made it to the other side and was relieved to find the terrain flatter than the 45-plus degree hillsides he had been battling up to that point.

But it was still rain forest, still rugged. And Mark was beyond exhausted. He had to concentrate to lift each foot up and over vines a mere 15 centimeters off the ground. Sometimes he had to reach down with his hands and pick his feet up and over the vegetation. Mark could only go a meter at a time before having to take a rest, or stop and ponder how to get through the next blockade.

He walked for several hours before concluding that his body simply couldn’t go any further without rest. As soon as he made the decision, he noticed the forest canopy darkening around him. His heart sank for the second time that day, as he thought about the possibility of spending another night in the jungle. One night was acceptable. Two was not. Two was too close to forever.

And yet, his body just wouldn’t go anymore. He laid some leaves down on the ground and then, against his better judgment, laid himself on top of them and promptly fell asleep. Meanwhile, it started to pour.

The slip

It wasn’t a huge, raging river. This branch of the Carara River was 8-9 meters across and up to a grown man’s mid-thigh in the middle. But one little slip of the foot was all it took for Mark to get carried downstream, deep into the rain forest. Worse still, no one saw him do it, knocking a good chunk off his odds of getting rescued.

Mark was already tired at that point in the bike race, about 40 kilometers into a 108-kilometer day. The length of the race wasn’t the problem – the 55-year-old had done plenty of races that long in Colorado. In fact, he first met the founder of La Ruta de los Conquistadores, Román Urbina, at a 161 km race near his home in Pine, Colorado. It was the humidity that was killing the man from bone-dry Colorado. That and the mud.

La Ruta de los Conquistadores has been held annually since 1993. The route is generally the same each year, climbing a cumulative 8,800 meters (29,000 feet) over five mountain ranges from west to east coast. It is supposed to mimic paths blazed by 16th century Spanish conquistadors, yet, as race organizers and finishers like to boast, the apparently out-of-shape colonial explorers took 20 years to traverse the country while La Ruta cyclists do it in three days.

There are those who race La Ruta to win, but most do it for the experience. For some, like the one-armed Costa Rican man who’s done the race more than half a dozen times, and the injured U.S. vets who race as part of the Ride 2 Recovery program, just being there is a big deal. “It might sound a little cliché,” says La Ruta founder Román Urbina, “but the journey is the destination, actually.”

This year, the first leg of La Ruta – the hardest day – set off from Playa Herradura, a beach town on Costa Rica’s central Pacific coast, at 6:10 a.m. on Nov. 5. Racers were told that temperatures in the valleys they would cross could reach 41 degrees Celsius (105 F). The humidity on the coast was pushing 80 percent — and higher once cyclists turned into the rain forest.

The strongest of the six riders in Mark’s Colorado group had zoomed ahead early and Mark had been riding for most of the morning with his friend, John Gerritsen, and John’s 15-year-old daughter Madelynn. Mark had helped Madelynn train for the race and seeing her finish was, perhaps, his biggest goal.

The muddy sections of the trail – more like inclined trenches in some spots, filled with a half-meter of mud – were grueling to get through on two wheels. Mark helped a female rider up one of the sections (he’s that kind of guy) and then pushed himself on. John and Madelynn had ridden ahead, concerned about making it to the next checkpoint before it closed. The checkpoints along La Ruta have closing times and, as a safety precaution, if a rider doesn’t make it through by the established time, he or she gets picked up and carted to the finish line.

The checkpoints also have food and drink for the cyclists, and some living near the route set up their own support stations. Mark got to one of these stations, on the outskirts of Carara National Park, and stopped to eat some oranges and dunk his head under a makeshift shower. He felt better and continued on to the river crossing.

In a long race like La Ruta de los Conquistadores, competitors of comparable abilities tend to run across each other frequently. As Mark splashed river water on his bike to get some of the mud off, a familiar-looking man in a red jersey looked back at him while peddling away from the river. Mark figured he’d see him again soon. And then, his foot slipped.

This might have been nothing more than an unforeseen way to cool off if it hadn’t been for the little waterfall about 3 meters downstream from the crossing. He slipped down the fall – still holding his bike – and picked up speed.

At first, Mark instinctually kept a tight grip on his bike. After all, it was his transportation for the race. But after a few hundred meters of getting dragged through the rapids by the relatively-heavy appendage, he reluctantly let go.

Mark had enough wilderness smarts and had spent enough time in the backcountry of the western U.S. – some of it in kayaks and whitewater rafts – to know that he should try to stay on his back and keep his feet pointed downstream. That way he could see what was ahead of him and protect his head from rocks and branches.

The technique is easier said than done. As the current swept and swirled, Mark fought constantly to get himself back into the right position. He went under for long amounts of time, managing to pop up just long enough to catch a breath before being pulled down again. Though his ordeal would last another 30 hours, this was his darkest moment. “Am I really going to die in a river in Costa Rica?” he thought.

Then, just as suddenly as it swept him off his feet, the current whooshed him toward the bank, pinning him up against a log. He found solid ground with his feet, but the water was up to his chest and the current was strong. He stood there, back against the log, facing upstream, water pummeling into his chest, for more than an hour, completely drained. Later, Mark calculated that the river had carried him a mile and a half downstream.

Tree hugging

It was one of those crazily-angled trees that you snap a picture of to remember how cool the vegetation is in Costa Rican jungles. Mark did have a GoPro. It was strapped to the bike helmet that was still strapped tightly on his head. But he was too drained for pictures.

Plus, it was getting dark and the slope was impossibly steep. The small trunk — about 20 centimeters in diameter — growing horizontally across the incline seemed the only thing that could keep him from rolling down the hill in the middle of the night and back into the water.

Mark loosened the hip strap on his small, sport backpack. With the pack still on, he hugged his body against the tree trunk, wrapped the hip strap around his waist and the trunk and clipped it shut. This was how he planned to spend his night in the jungle.

When Mark had finally gathered enough strength to pull himself out of the water that afternoon, he flopped down on the only section of the rocky bank that wasn’t too steep to hold him. In front of him and behind him, the river bank was like a wall, 3-5 meters tall, starting as rock and morphing into a sheer, muddy bank covered in thick vegetation. He counted his losses.

Cellphone? Gone.

GPS? Gone.

Bike? Long gone.

Shoes? Both had fallen off at different points in the river.

Shortly before his whitewater adventure, Mark had taken all the food he was carrying with him – if you can call energy gels and gummies “food” – out of his backpack and stuffed it into the pockets of his jersey for easier access. It was all gone.

He hardly had any water left in his CamelBak because he had been drinking so much during the morning’s ride.

He did have a light jacket and a small first aid kit in his backpack. And a few packets of Cytomax. He had already ripped open one packet and eaten a little while standing at the edge of the river in hopes that it would give him a boost of energy to help him get out of the water. Now, in need of another boost, he poured a little more of the dry powder down his throat.

He also still had his bike helmet on with the GoPro camera strapped to it. In fact, he had taken his helmet off when the river finally secured him against the bank and pointed the GoPro at himself.

“Well I stopped now, so I’m good,” he narrated into the camera. “But I have no energy. I don’t know how I’m going to get out of this.”

Now on the rock, he again pointed the GoPro at himself.

“I’m just going to have to lay here the rest of day,” he said limply into the camera.

He’s not sure why he recorded these status updates. Maybe it was so there would be some evidence of his ordeal, in case he didn’t make it back. But he fully intended on making it back. In any case, he later lost the GoPro somewhere in the jungle.

Mark laid on the rock by the side of the river for several more hours, trying to come up with a strategy.

At some point he found himself staring at a rock in the river that looked like it had a face on it, thinking about Wilson, Tom Hanks’ volleyball companion in the film “Cast Away.” He stared and stared until some other part of his brain butted in and forced him to snap out of it. The water flowing around the friendly rock was rising. He had to move.

Mark ate some more Cytomax and started up the perilously steep bank. He wasn’t more than 15 meters up the hill when it started getting dark. He spotted the horizontally growing trunk and declared it his sleeping partner for the night.

Not that he would be getting any sleep. It would be the longest night of his life. Every 10 minutes seemed like an hour – though Mark had no way of calculating the passage of time. He was beyond tired, but nevertheless sleepless.

It rained on him on and off. Mark listened to sounds coming from animals in the jungle around him but had no idea what they were. He went over and over his plan for getting out of there the next day and being rescued.

And, because it’s the kind of guy Mark is, he thought about the other members of his biking team and fretted that he had ruined their race and their trip to Costa Rica. He especially thought about Madelynn and how hard she worked to get there, how he had so wanted to see her finish La Ruta and become, perhaps, the youngest female to do so.

Still, in the midst of the tedium and discomfort and endless waiting for daylight, Mark marveled at the fireflies lighting up the jungle around him — the first time he’d ever seen the insects.

When the vegetation began to slowly come into greater focus, his mind kicked into high gear as he went again over his escape plan. As soon as it was light enough, he unstrapped himself from the tree trunk and continued up the hill.

It was slow going. Mark had to test his weight on every root he used as a step, every vine he used to pull himself another few inches up the declivitous slope, to make sure it would support him. He occasionally grabbed a vine covered in black spines, like sewing needles, which would come off in his hands and later take more than an hour to pick out.

Mark figured he needed to climb until he found a flat enough spot to traverse. He would head upstream, and then back down to the water near, he hoped, the spot where he initially fell in, where the road crossed. If he could just get to the road, someone would find him.

The rescue party

Ben Hobgood stood by the bus near the finish line in his cycling gear, shivering while it poured. He brightened when he saw teenage Madelynn’s neon orange helmet emerge from the darkness, illuminated by the headlights of several quads that were accompanying the last of the day’s racers. Madelynn and her dad, John, greeted the rest of the Colorado crew. John did a quick scan and asked, “Where’s Mark?” It was 7 p.m. – some nine hours after Mark slipped into the river. And yet until then, no one thought he might be missing.

“I don’t know,” Ben replied, “I thought he was probably with you.” The fact that no one in Mark’s crew knew his whereabouts was cause for some alarm, but not total alarm. It was a hardcore adventure race. Things happen. Maybe he had gotten sick or had to give up early and had already been taken back to the hotel.

On the other hand, they thought, Mark was in excellent shape for the race, and John had thought Mark would overtake him and his daughter at some point during the day. “The worry escalates over time in this kind of situation,” Ben would later reflect. The group got to their hotel, where other La Ruta riders were staying, and found that Mark wasn’t there either. The worry level ticked up.

In the meantime, Román, the race organizer, was with a crew doing a final sweep of the trail to look for stray racers. They do it every year, after every leg of the race: One group heads out from the finish line, another from the start of the day’s leg, and they meet in the middle. To do these sweeps, Román hires former first responders and ex-cops. And, he gets a “baquiano,” a local who knows the terrain like the back of his hand, to be a scout.

That night, three quads – Román was on one of them – swept the trail twice, looking for Mark. It was pouring rain and very cold, Román remembers. They went as far as they could with the off-road vehicles before the trail became impossible to pass. No sign of Mark.

Around 4 a.m., Román called off the search and made sure everything was set up for a new search party that would set off as soon as there was light.

Mark’s five friends gathered in one of their hotel rooms and sat – into the wee hours of the next morning – hashing out the situation. Who saw Mark last and where? What kind of shape was he in? What else did they know about the ride that day that might provide a clue as to Mark’s whereabouts? Should they contact the U.S. Embassy? Perhaps most vexing, when and how should they tell Mark’s wife?

Mark’s wife Tammy had a reputation as a bit of a worrier, even though she herself was an adept outdoors woman. After much debate, they decided they would wait to call her until the next morning. They hoped Mark would turn up in the meantime, perhaps after a good night’s sleep and a beer at the house of some kind-hearted Tico who took him in when he got lost.

Around 5 a.m., the second search party set out. One group left on horseback from El Sur, a tiny village just south of Carara National Park and the site of the first checkpoint, which they knew Mark had gone through the previous day. The other group left on quads from Lagunas, located just north of the park. The two groups planned to meet in the middle, and find an exhausted but otherwise healthy cyclist along the way. They met five hours later. No cyclist.

Román needed outside help. He called the Red Cross and the National Emergency Commission, which immediately sent people to join the search. By mid-morning there were around 20 professional rescuers looking for Mark. People offered Román helicopters to help with the search, but when looking for someone in a dense jungle, helicopters aren’t very useful.

When Román’s search party didn’t turn up Mark, his friends decided it was time to tell his wife, Tammy. They designated Jeremy to make the call. Jeremy’s wife was friends with Tammy and he was probably the most sensitive of the crew. He had gotten physically ill worrying about Mark the previous night. As a fly-fishing guide and whitewater kayaker, he knew how dangerous a river could be.

Tammy was at her office in Colorado when she got the call – at precisely 9:11 a.m., she remembers. Tammy had a feeling something was wrong even before she got the call. She had barely slept the night before. Mark hadn’t called after the first leg of the race like she thought he would. But that wasn’t the main reason for her unease. She had a premonition. And she had dreamed the night before that Mark made it through the first two legs of the race, but didn’t finish the third.

Still, she figured maybe her husband had broken a leg or an arm, not that he was missing. When Jeremy broke the news, Tammy wanted to fly to Costa Rica immediately. But Jeremy and the others talked her out of it. They had things under control and they all needed to give the rescue mission more time. The waiting game continued.

Twenty-four hours passed since Mark went missing. Then 26, 28, 30. The hours ticked by while Mark’s chances of being found alive dwindled.

When light began to fall on that second day, Mark’s crew started to freak out. They discussed whether they should push the Red Cross to get helicopters up in the air, whether they should put pressure on the U.S. Embassy to put pressure on others to beef up the rescue mission. And then, around 5:30 p.m., John’s cellphone rang.

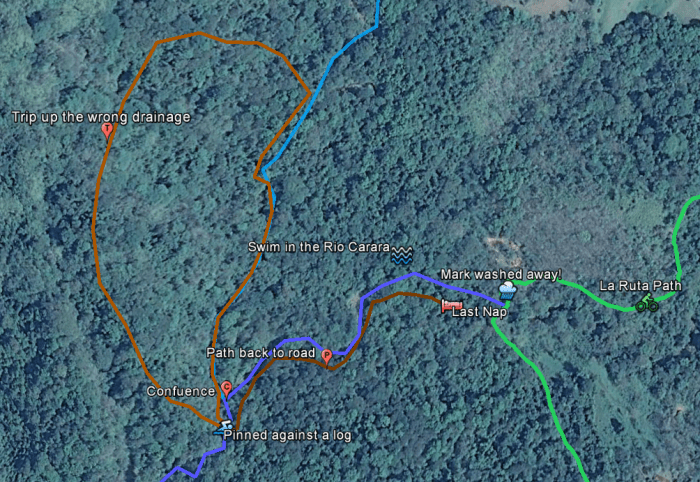

The Colorado cycling team put together the map above – using GPS data, Google Earth and their best estimates – showing Mark Lyons’ likely route after he slipped in the river.

Found

There are many reasons why, if anyone in that race was going to get swept down a river and have to spend the night in the jungle, it was Mark. For one thing, his thick Colorado blood (his mountain home and yard were covered in snow when he got back from Costa Rica) helped him withstand the cold, rainy night.

For another thing, Mark exudes calm and confidence.

“I was very focused,” he said later of his mental state while lost – Mark prefers the term “missing” – in the jungle. After he escaped from the rushing river with its sharp rocks, whirlpools and other hidden traps, he was pretty sure he’d eventually make it back to safety. “I wasn’t worried,” he said in an interview a week after the ordeal. Mark narrated the details of his misadventure while sitting in a chair, poolside, in Jacó, his walker at his side. His ankles were swollen to the diameter of softballs and his legs and arms were covered in gashes, some of them oozing puss.

“I never thought, ‘I’m not going to survive,'” Mark said. “None of that ever went through my head. I just thought, ‘I have to get back to that road.'” The road. While Mark drifted in and out of sleep on his blanket of leaves that second afternoon, he heard a faint sound of vehicles. The road!

“My first thought was, ‘I’m just going to sleep here and I’ll get to the road tomorrow,'” Mark recalled. “Then I thought, ‘No, I want to get there today.” Even after his mind was made up, it took him 15 minutes to get back on his feet.

He headed in the direction of the vehicle noise. It was another 45 minutes of slow, painful going until he saw it. He was ecstatic, but exhausted. “Exhausted is such a complete understatement,” Mark said after he got out of the CIMA private hospital outside San José, where he spent six nights after his sleepless one in the jungle. “I don’t have words for a lot of what happened, how I felt,” he said.

When Mark reached the side of the road, he collapsed onto a chair-sized rock. “Every once in a while I would yell out, ‘Hola!'” he said later. “That was all the energy I had.” He sat on the rock for nearly an hour as it got progressively darker. Mark noticed a flat patch of greenery nearby and contemplated laying down there to wait.

“It took me about 15 minutes to get off the rock,” he said. “I just sat there thinking about it.” He finally willed his body to rise. He took one, two, three steps toward the green patch. “I didn’t even hear the quad at first, and then all a sudden he was there.” The quad rider’s jacket said “Policia.” Soon after, a Red Cross worker showed up.

“And then, right there, I was like, ‘That’s it. I’m done. I did it.'”

Postscript

On the phone from Colorado two weeks after his La Ruta adventure, Mark’s voice was weak with pain. While some of his wounds had healed, other problems were emerging. Doctors had discovered several broken ribs, which made breathing agonizing.

When rescuers found Mark, he had mild hypothermia and could barely move. But doctors found no broken bones and didn’t expect any serious long-term damage. Nevertheless, Mark had brushed up against death. Doctors at CIMA told him his kidneys were dangerously close to failing because of the buildup of toxins due to overexertion.

“Looking back on it, I don’t know how I did a lot of that stuff,” he said from Colorado. Despite his still-fragile health, Mark said he plans to return to work later this week at the pizza shop he owns with a partner.

When Mark’s La Ruta cycling crew got the news that he had been found, they rushed to the hospital outside San José to see him. They stayed until the wee hours of the morning. Then they all got up at the crack of dawn and finished the race.

See more photos of La Ruta from Tico Times photographers here