On July 25, 1989, Costa Rican President Óscar Arias — having expropriated the land where a mile-long, secret, Nicaraguan Contra airstrip was located — inaugurated Guanacaste National Park, 82,500 hectares of land embracing the lowland dry tropical forests of the Santa Elena Peninsula and extending upward to Orosí and Rincón de la Vieja volcanoes and the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve.

“It is the will of the Costa Rican people that these lands no longer be the scene of armed conflicts or used to promote violent actions alien to our interests. Instead we shall see students, teachers, scientists and naturalists, with books and scientific instruments,” Arias said.

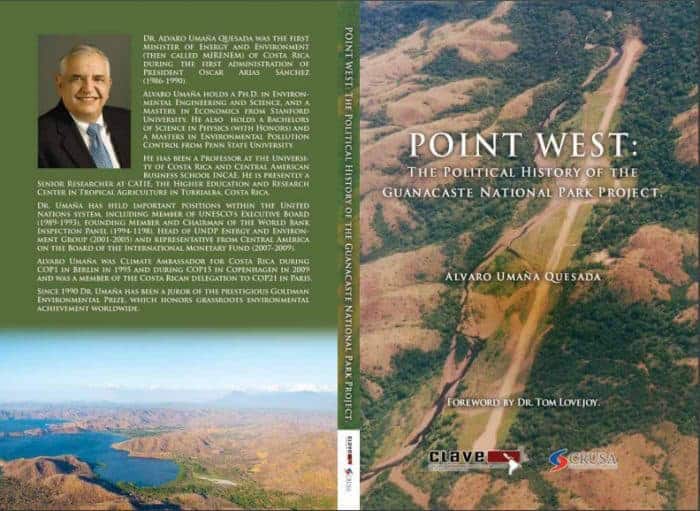

In his recently-released book, “Point West: The Political History of the Guanacaste National Park Project,” Arias’ Minister of Environment and Energy Álvaro Umaña describes the armed conflicts that played out on the peninsula, starting in 1856, when a ragtag Costa Rican army confronted and ejected the U.S. freebooter William Walker from a ranch on the peninsula.

On the motivation behind his riveting account of Lt. Col. Oliver North’s airstrip, Umaña said: “The current generation of Costa Ricans do (sic) not know that in 1986, Peninsula Santa Elena, …, was the site of events similar to what occurred in 1856: clashes between the U.S and Costa Rica. In the more recent cases the mercenaries were not Walker’s troops probing south from Nicaragua but rather North, (then-U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Elliott) Abrams and their hired guns.”

It might come as a surprise to many who think of Costa Rica as a steadfast friend and partner of the U.S. that Costa Rican officials would see the U.S. as intruding, “a clash between the U.S. and Costa Rica,” in an unwelcome effort to use the Santa Elena Peninsula to attack neighboring Nicaragua. But it didn’t come as a surprise to Arias, who based his peacemaking efforts on Costa Rica’s pacific, civilian traditions.

To say that the Reagan Administration was oblivious, ignorant or plain didn’t care about local sensibilities or the history of the region when advancing its policy in Central America is an understatement. (Umaña quotes Abrams as saying, “We’ll have to squeeze (Arias’) balls” over the airstrip.)

Still, in Umaña’s account, aversion to the Contra presence in Costa Rica was hardly universal among Ticos. Many supported the Contra effort, first among them, Benjamín Piza, Minister of Public Security under President Luis Alberto Monge, Arias’ predecessor.

Piza cooperated with the construction of the airstrip, which was built in an effort to circumvent the Boland Amendment passed by the U.S. Congress to cut off U.S. aid to the Contras.

Piza even came up with a cover story in the event that the airstrip was discovered: a memo he dictated to North in which the owners of the property, a phantom Panamanian company called Udall Resources Corp., gave the Costa Rican Civil Guard permission to use the land for training.

All Piza asked for in return was an Oval Office photograph with President Reagan. “Piza got his photograph and North got his airstrip,” said Umaña.

But if Costa Ricans were divided on the Contras, so were U.S. citizens. The scandal that erupted when it was discovered that the Reagan Administration was using proceeds from arms sales to Iran to fund the Nicaraguan Contras gave Arias’ many allies in the U.S. Congress the opportunity to put the Reagan Administration on its heels for its actions in Central America.

Umaña, currently a senior fellow at the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE), said that the Iran-Contra scandal, in which the airstrip played a large role, provided an opening for the peace plan.

“Fortunately for future democracies in Central America, President Arias prevailed, and he was able to derail the U.S.-backed war effort and save thousands of lives,” Umaña wrote. “His resistance to major power meddling in Central America, as typified by the Iran-Contra Affair, then opened a unique window of opportunity to launch his peace initiative in the region for which he was eventually awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1987,” said Umaña.

In “Point West,” Umaña traces the construction of the Santa Elena airstrip, Arias’ unsuccessful battle with the Reagan Administration to keep the Contras from using it and the efforts by the U.S. to keep “Point West” under wraps.

He tells of the trials of Reagan Administration officials and the legal battle over the expropriation of the airstrip land.

Umaña also talks at length about ecological restoration of the Guanacaste Conservation Area, which includes Guanacaste National Park and Santa Rosa National Park, and the protagonistic role of University of Pennsylvania ecologist Daniel Janzen.

Janzen appears in many roles throughout the book: as a reluctant witness to the overflights of cargo planes (Janzen kept silent about the airstrip out of a justified fear that he would be ejected from the area); a hyper-committed scientist who lets jungle flies lay their larvae in his skin so that he can study their life cycle; an avid promoter of purchasing land for Guanacaste National Park to complete the ecological restoration that he dreamed of; and a negotiator with the owners of the airstrip land who refused the $1.9 million offer made by President Daniel Oduber when he expropriated the land in May 1978.

Six successive presidents tried and failed to negotiate a deal with the owners, until 1995, when President José María Figueres finally took the case to a World Bank arbitration panel, which awarded the owners $16 million for the land.

In the meantime, the Costa Rican government had raised $64 million for the park from 17,000 donors around the world.

In the end, “Point West” is a story of how Costa Rica managed to exert its sovereignty against formidable forces which had decided to run roughshod over any law that got in the way of overthrowing the Sandinista government.

I once showed a Miami Herald article to Costa Rican Ambassador to the United States Guido Fernández which said that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency was planning to step up efforts to launch a “southern front” through Costa Rica.

At the height of the Contra war and the beginning if Arias’ peacemaking efforts, Fernández said, “That is what we have to stop.”

When I asked him how he planned to do that he replied, “How does an ant fight an elephant?” “Point West” goes a long way toward answering that question.