In December 2020, scientists from the Faculty of Microbiology of the University of Costa Rica (UCR) and the Costa Rican Institute for Research and Teaching in Nutrition and Health (Inciensa) concluded there is a local strain of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

This mutation does not make the virus more lethal, contagious or aggressive, researchers say, though the strain is becoming more common in Costa Rica.

In the December 2020 report, the so-called T1117I variant registered a presence of 14.5% in the 138 cases studied. A January 2021 report shows that that number has increased to 29.2%. This significantly exceeds the strain’s international frequency of under 1%.

According to the international GISAID database, a platform that promotes the rapid distribution of information related to viruses (including SARS-CoV-2), New Zealand, Australia and Bangladesh have reported the variant. However, those nations have accounted for single-digit cases.

Other countries that have also reported T1117I, but with minimal cases, include Chile and South Africa.

Now the question is why? What does the variant mean for Costa Rica, and for the battle against the coronavirus?

To answer these questions, we turn to Dr. José Arturo Molina Mora, bioinformatic microbiologist at the Center for Research in Tropical Diseases (CIET), Faculty of Microbiology, and coordinator of the virus genomic analysis project from the UCR.

In a previous interview, you explained the work that the UCR carries out with Inciensa to monitor the behavior of the virus. How many variants, in general, have you managed to find to date?

Dr. José Arturo Molina Mora (JMM): “In the last interview I said we had described up to 15 mutations per genome and that these mutations were also reported elsewhere in the world. To date, we have already detected up to 22 mutations per genome, for a total of 283 different mutations in all the genomes that we have analyzed together.

As before, we have no association of viral genomes or virus types with mortality. In other words, regardless of the variant with which you have the infection, at the moment a patient is just as likely to die (or not) from the disease caused by the virus.”

What is the importance of this mutation vigilance?

JMM: “For the country, it is very relevant to study the complete genome and detect mutations because it allows us to know if there is any variation in how the virus is transmitted, if it would modify the severity of the disease or, even, if it could cause changes in the effectiveness of the treatments or vaccines.

SARS-CoV-2 mutations can be neutral, positive or negative. In other words, some mutation or variation could worsen the situation or, instead, show an adaptation that causes the situation to improve for us.

A mutation is not necessarily synonymous with something bad. But it could be that some are more aggressive and it is precisely for that reason why they must be watched. If we don’t do this job, no other country in the world will come here to do it.”

Let’s talk about this new variant, T1117I, which in Costa Rica is present in 29.2% of the cases studied, when at the international level it does not even reach 1%. How did you come to find it?

JMM: “To find new variants, we do a mutation analysis, which consists of studying the genome. The SARS-CoV-2 genome has 29,903 letters (nucleotides).

So, in that line of letters we see if there is a variant and we determine its position in the genome sequence. Thus, we know what the alteration is. For example, at the original Wuhan genome position 14,408 there is a reference C (cytokine).

In the Costa Rican case, and in most genomes of the world, there is a mutation in that position 14,408 that has been called D614G of the spike.

Instead of having a C, 98.9% of the strains in Costa Rica have a T (thymine). This mutation is one of the most common in the world. But now we report an almost exclusive mutation for our country at position 24,912 called T1117I of the spicule.”

And when did you realize that we had the T1117I variant in Costa Rica?

JMM: “In December 2020, we became aware of the T1117I. When you’re doing the study, you go mutation by mutation to see what the effect might be. When I found that variant, I said, “What? Wait a minute!” And I began to investigate further.

In the December report, which analyzed the March-August period, we said that the T1117I in Costa Rica had a frequency of 14% in August, while in the world this mutation did not reach 1%, and that it is very scarcely reported by other countries.

This variation is very predominant in Costa Rica. There are a few cases in Colombia, and very few in Malaysia and Australia.

As of January 2020 we updated the information with genomes obtained from cases up to November and we see a 29% frequency in this mutation in Costa Rica. In other words, it has already doubled in our country in just three months.

So, could this variant, the T1117I, be considered the most common in Costa Rica?

JMM: “It is not the most frequent, but it is the one that is increasing the most with respect to its history. Let’s look at the case of the D614G variant of the spicule. At the beginning we had it at 95%, then 98% and now at 99%.

These percentages reflect that the D614G variant has always been very high and greater than 90% of the sequences. But this one, the spicule T1117I, was previously at zero and stayed that way for several months until May. Now, it is increasing.

If the London variant arrives, to cite one case, an increase is expected to occur, similar to that reported in England and the United States, because it is suggested that it has greater transmission rate.

The important thing here is that we study in detail the T1117I variant before the scientific community. Although we did not have the first case, we did make the first report with a sustained increase to levels not observed in any other country. The first case was in Germany.”

Do you know what caused the origin of this mutation in Costa Rica?

JMM: “No. There are many hypotheses. As the first reported case was in Germany, one option is for a German person to come to Costa Rica and bring that mutation. That could be an explanation.

Another is that it may have originated entirely in Costa Rica, independently from Germany. The scenarios are very complex.

What we do know is that the genomes that circulate in the country are the product of multiple introductions. Once I was asked, ‘Is COVID-19 in Costa Rica the fault of the first infected foreigner who came to the country?’ Not really. He was a case, but there are many more reports of people who brought it from other countries, including Costa Ricans.

Like other countries in the world, the genomes that circulate are the product of multiple introductions by people from various nations.”

Does the mutation cause a change in lethality or infection rate?

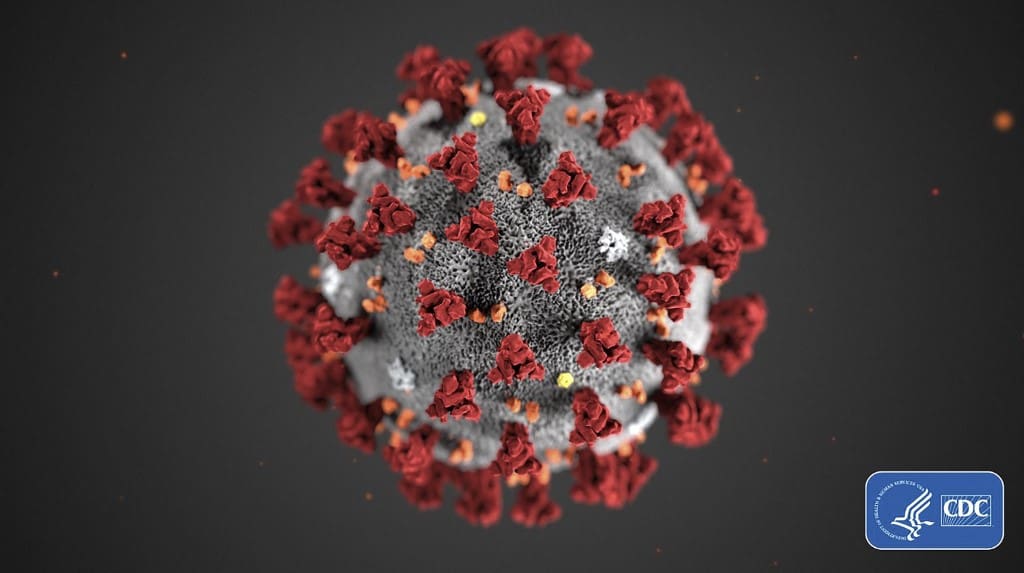

JMM: “The genetic material carries the instructions for how the virus is going to assemble its spicule (those spikes that it has in the form of a crown and that is its key to enter the human cell). Oligomerization gives the virus protein its final form and the ability to interact with the human cell.

If we focus on the T1117I mutation, bioinformatics analysis predicts that it is very likely that it will not have a major effect on how the molecule acts with the human cell. Therefore, it should not affect any change in the presentation of the disease.”

What about impacts on vaccine efficacy?

JMM: “If this mutation were close to the sites where antibodies are recognized, it would be worrying there because it would jeopardize the efficacy of vaccines. But this is not the case. The mutation, being so far away, should not affect the vaccine.

Of the mutations found in the world, at the moment, perhaps that of England is the only one whose transmission seems to be increased.”

How many mutations would it take for a vaccine not to work?

JMM: “A simple mutation can lead us to a total transformational change if it is at a key point, but it could also take several mutations. A simple change in the SARS-CoV-2 proteins could have a very striking effect on its three-dimensional shape. That is why vigilance is important.

For each month, the virus is expected to mutate once or twice in Costa Rica, on average. It is expected that, within three months, 26 or 28 mutations will already be circulating that give the virus some additional characteristic, whether positive, negative or none at all. This is what surveillance is for.”

What specific benefit does this T1117I variant give the virus, since it does not make it more lethal or contagious?

JMM: “Here it is perhaps important to mention that not all mutations favor the virus. But the accumulation of mutations maybe yes. For example, what happens if we are registering this T1117I, but then this virus at some point accumulates a new mutation that begins to favor over time in a similar way?

The result is an accumulation of mutations, and there you would begin to see the effect. As I said, this is not a requirement either, because a single mutation can change the whole picture.

At the moment, we do not know the advantages of this mutation to the coronavirus. We would have to wait and continue monitoring its behavior.”

So, more studies are still required to determine if the variant, along with other mutations, changes the picture?

JMM: “That’s right. The studies we do change their interpretation over time. This has happened a lot with other mutations. Although at the beginning it was believed that some generated increased transmission, later it was concluded that they did not. Something similar could happen to us with the TIII7I mutation.”

Finally, Dr. Molina, what can the Costa Rican population expect in the coming months?

JMM: “The most important thing about this, which applies to the mutation in Costa Rica, is that at the moment none of the mutations has reported a change in the way the disease is going to develop.

COVID-19 continues to depend on risk factors. You have to keep heeding the measures. Also, that regardless of whether the GH, GR or G version of the virus is going to reach me, we must prevent infection from an individual and collective point of view, especially high-risk people.

From the UCR and Inciensa, we are going to continue detecting mutations, but this will surely not change the rules for controlling the virus.”

Read the full scientific article here: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.12.21.423850v3.full.pdf

A version of this story was originally published by Semanario Universidad on January 28, 2021. It was translated and republished with permission by The Tico Times. Read the original report at Semanario Universidad here.