If you live in a predominantly Tico barrio, you are likely familiar with vendedores ambulantes. These are the door-to-door salespeople who pass through selling eggs, mora, pejibaye, mamón chino, tamales, tomates, pasteles, and mucho mucho más. They may be on foot or in a vehicle that slowly passes by the houses while the vendor calls out their products. Some have speakers mounted on car roofs, while others rely proudly on their strong vocal cords.

It will come as no surprise to know that these vendors are supposed to have a municipal license or patente (permit) to sell door to door. Likewise, it is no surprise that none of those I have asked—making sure they know I am not working with the Muni—have possessed the patente. For every regulation and law in Costa Rica, there are two ways to skirt them. The odds of someone from the Muni showing up in this barrio and stopping someone because they don’t have a permit to sell their product are near zero.

As long as you reside in the informal, on-the-street, cash-only economy, that trip to the Muni with all the requisite documents gathered, to sit around half a day before you can pay to get a patente, won’t be necessary. But once you hang your shingle and do business with any business that has its own patentes, you too will need a patente.

I have worked both sides of the street. Years ago, I baked breads and cookies and sold them directly in two different beach towns. It was a cash-and-carry operation—no patentes, no receipts. Later, I opened a storefront that lasted eight months. There, I ran the municipal gauntlet and paid a patente every three months.

The same week I closed my shop and made my operation informal again, I received the quarterly patente bill from the Muni. I ignored it. I was no longer a storefront operation but one baking from the cuarto de pilas of my house. Flash forward a couple of decades. After a long time away, I returned to live in Pérez Zeledón. I no longer baked for a living nor did anything that would require a patente.

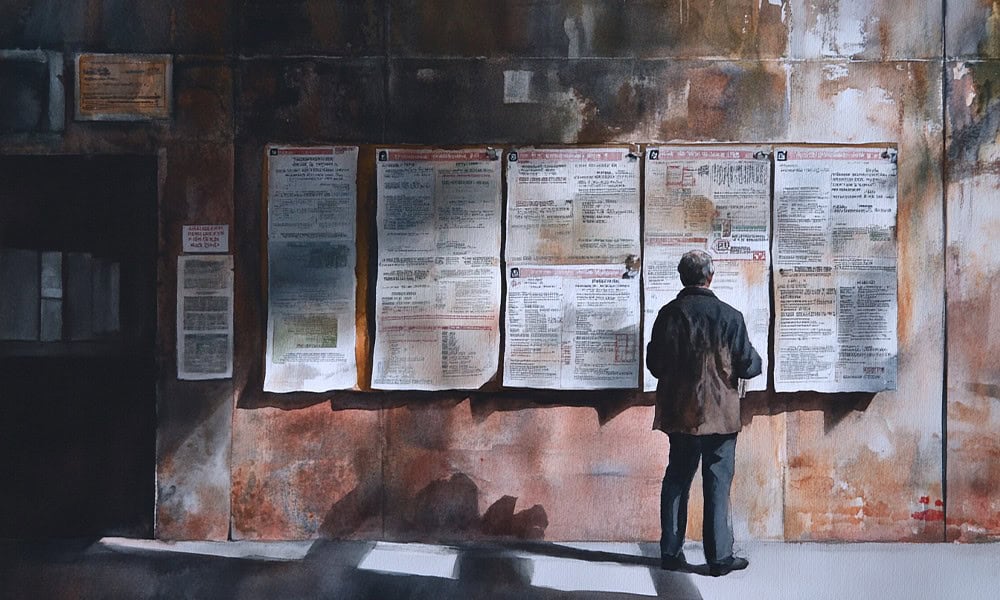

One day, I was in town and saw an enormous billboard on the front wall of the main entrance to the Muni. The board was a Wall of Shame—a list of everyone who owed the Municipalidad money for unpaid patentes. I scrolled the list—it was alphabetical—and there was my name. The amount due, once a few thousand colones, had been padded with interest and fines to over 100,000 colones.

It was hardly a select group of debtors. According to the Muni’s own numbers, there were 29,000 names on the list. I considered offering to settle but knew it would involve hours of my time waiting to talk to the right person, inflexibility on the amount, and frustration with a system I do my best to avoid.

To an extent, the periodic posting of debtors worked. According to the Muni, the most recent Wall of Shame led to about 3,500 defaulters paying, which reduced the amount owed from 950 million colones to 725 million colones. There are still over 25,000 names on the list, mine included.

I have decided that the day the Wall of Shame is down to one name—my own—is the day I will pay. Because once your name and balance due is imprinted in the machinery of the local bureaucracy, it will only be removed upon your death, if then.