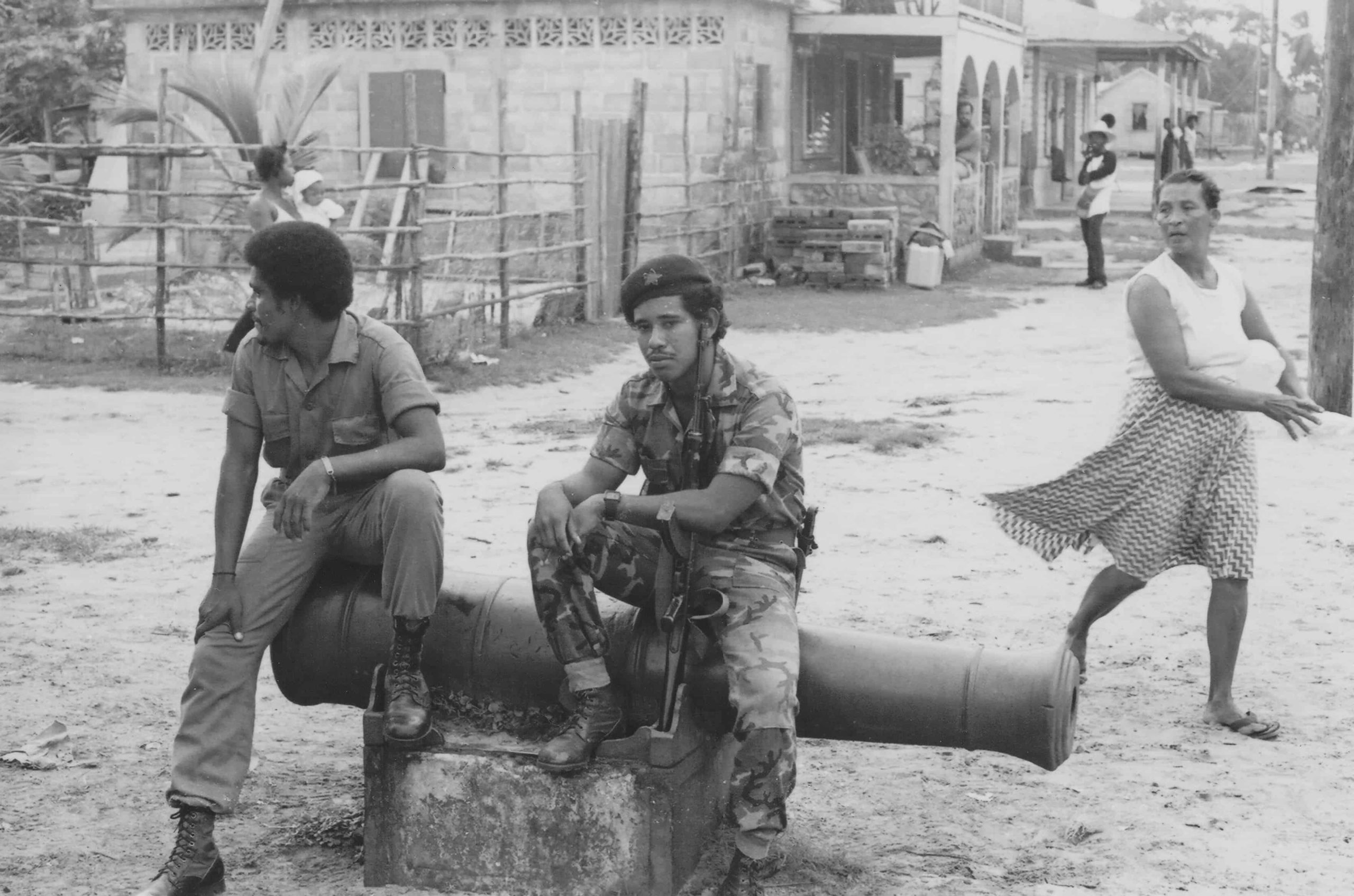

On and off from late 1985 through 1988, I fought with ARDE (The Democratic Revolutionary Alliance) Frente Sur deep inside Nicaragua against the first Ortega dictatorship.

I remember it was a rainy day in San José, Costa Rica, when I showed up at a “Mercado de Los Pulgas” and said the only Spanish I knew: “Yo busco A.R.D.E.”

I remember crossing the Río San Juan at 3 a.m. and being dropped off in dugout canoe on the enemy controlled Nicaraguan side, hoping I wasn’t stepping through a minefield.

Sometimes we’d get dropped off in kilometers of swamp up to our necks, holding AKs overhead and inhaling mosquitoes with every slippery step.

Then came an 8-day march just to get to the real war zone around Nueva Guinea. The way back to Costa Rica was even worse. We’d arrive hungry and tired from the long and usually muddy march over the montañas. Typically we’d have dozens of civilian refugees with us.

If we got close to the Sandinista lines on the river and the baby was crying, we would give the baby a shot of rum. If that didn’t quiet him down, we would have to march back and try again the next night.

We’d chop down banana plants with a machete and tie the trunks together with vines or string and throw the babies, weapons, and backpacks in middle and paddle across the San Juan River. We’d swim next to the makeshift raft in our underwear, hoping the Sandinistas didn’t catch us in this exposed position.

We hoped the rumors of fresh water sharks were untrue.

I remember in 1986, after surviving a Sandinista offensive against campesinos in southern Nicaragua, I had to swim that river weighed down by 30 pounds in weight and with a distended belly from parasites and mountain leprosy on my leg. I collapsed in the bushes on other side, huddling with two buddies taking shelter from the rain under our plastic tarp and having a hard time sleeping because my buddy Rudi’s nose was rotting from leprosy and the smell was keeping me awake.

The next day I had the strength to make it to a friendly Tico’s farm house and made mistake of hooking my hammock up to the chicken-roosting tree.

I was too drained to move, so our Tico friend sat in tree chasing the chickens and roosters away till darkness fell.

I remember the incredible greenness of Nicaragua. The rivers, the mountains. The flocks of parrots. The packs of wild boars making paths through streams, and tepesquintles (jungle pacas). Those giant macaws with red, blue, and green, which people kept as pets. I remember combat in places like El Verdun and Los Ranchitos. I remember being ambushed twice.

I remember telling stories by campfires and eating pinol, guajada, malangas, yucca and beans, occasionally washed down with chicha and maybe an occasional slug of guaro.

I remember the off and on again flakey U.S. military support. The three-ring circus of bureaucracy, the division of the politicos juxtaposed with the brotherhood of commandos on the inside. Contra commandos used to call politicos “vampiros resentidos.” Back then, and still now, they were all corrupt and useless.

Most of all, I remember the murders of campesinos, the zones with the burnt-out houses such as in the area of Río Tule. The empty zones around Nueva Guinea whose population was forced to march to resettlement camps, and the never-ending parade of dying kids with distended bellies. We would only have a few bucks to our name, and had to pick and choose who would get medicine.

I remember the “pitufos” (child soldiers whose families had been wiped out by Sandinista Popular Army, or EPS and were raised by the Contras) and the and commandas, the female commandos sacrificing just like the men. The poignant stuff. The traitors and those who switched sides.

Throughout it all, the Contras hung tough. Betrayed, badmouthed and ripped off over and over again, the FDN, ARDE Frente Sur and YATAMA forces on the inside of Nicaragua united and like the tail wagging the dog, the U.S. was forced to either accept and support the unification or go back to betting on the latest corrupt politico de jour.

For the first time in the war, the U.S. got it right and my favorite President, Ronald Reagan, was able to push an aid package through congress that actually got to the fighters in the field.

Some of the happiest moments of my life were watching those life-saving parachutes float down in the middle of the night with those giant bonfires giving the pilots a target nobody could miss, even in the rain.

The noisy DC-6 propeller planes and bonfires didn’t matter – we had 100 percent campesino support and I doubt if the piris (slang for Sandinista soldiers) shot down even one out of 100 of the supply flights.

At that point, we started shooting down the Soviet-built “Flying Tank” MI-24 gunships, and launching major operations in every corner of Nicaragua, including the devastating attacks on the Rama highway and at Siuna and El Bonanza. As momentum swung our way, we found ourselves turning away recruits as Ortega was scrounging for more soldiers by rounding them up in Managua movie theaters and city bus stops.

U.S. journalist Peter Collins of ABC News did a semi-undercover piece in which he estimated a 20 percent desertion rate in the EPS, which sounds about right to me. Make no mistake, by early 1988 we had Ortega and the EPS on the ropes, but the only ones who understood that were the Ortega brothers, his commanders, the people of Nicaragua, and the Commandos of the Nicaraguan Resistance.

I think even our American supporters in Honduras and elsewhere didn’t quite grasp how quickly things turned in Nicaragua and how close we were to victory.

That’s when everything went horribly wrong and the first deal with the devil took shape. Reagan’s second term was winding down and he was beset with legal distractions. U.S. President George H. W. Bush, a pale shadow of Reagan, was elected.

In Costa Rica, in spite of the murder of various Tico civil guards and civilians on the San Juan River, Oscar Arias Sánchez brought his massive ego and disdain for the campesinos to the table.

Bush and Arias made a deal with the devil. Contras were cut off from outside aid, while facing down the largest and most wellarmed army in history of Central America.

Approximately two-thirds of FDN forces withdrew to Honduras, leaving once again ARDE Frente Sur and the more hardcore elements of FDN and YATAMA holding the bag.

The three-ring circus of corrupt politicos dutifully performed like house pets and signed bogus agreement after bogus agreement.

This was the original and most lethal pacto. This crushed all hopes for a free Nicaragua and should have proven once and for all you cannot compromise with thugs.

The 16 years from 1990 to 2006 were a sick and predictable joke. To me the second “pacto” was just a predictable footnote to the killer first one.

Many weakened and sold out over the years – all sold their souls by forming their own personal pactos. This is a Nicaraguan form of natural selection, but 99 percent of Nicaraguans haven’t been fooled and will never sell out.

I have a feeling Nicaragua has one more revolution in her. Let’s not forget the horrific consequences of the first pacto, and never compromise again on freedom.

“Jim Peregrino” is a U.S. citizen who fought as a counterrevolutionary fighter in the 1980s because “I was young and stupid and looking for adventure.” He joined the Southern Front ARDE and claims he was never paid to fight. Originally posted in 2019