I signed in at the entrance of Palo Verde National Park and drove down the main dirt road, wondering if I’d accidentally wandered onto a private ranch. It is an understandable sentiment as the 45,000-plus acres that make up the park were indeed a private ranch up until the mid-1970s, when the land was expropriated by the Costa Rican government.

As I puttered along, dodging iguanas that seemed too emboldened — or too comfortable — to move, I thought through what I had read about the park. I knew I was going to see birds, dry tropical forest, the Tempisque River and, hopefully, crocodiles. I also knew that I was going to be hot. I was not disappointed on any of these fronts.

After an interesting 15-minute drive I arrived at the biological station operated by the Organization for Tropical Studies. OTS operates in the park under an agreement with the Environment Ministry (MINAE). OTS offers accommodations which are typically used by visiting students and researchers.

The guide on duty, Gustavo Rodríguez González, 31, from Cañas, checked me in and confirmed that he was available for a free guided tour of the park later in the afternoon. I am not accustomed to hearing the words “guided” and “free” in the same sentence so I confirmed that my poor Spanish and I had interpreted this correctly. I had.

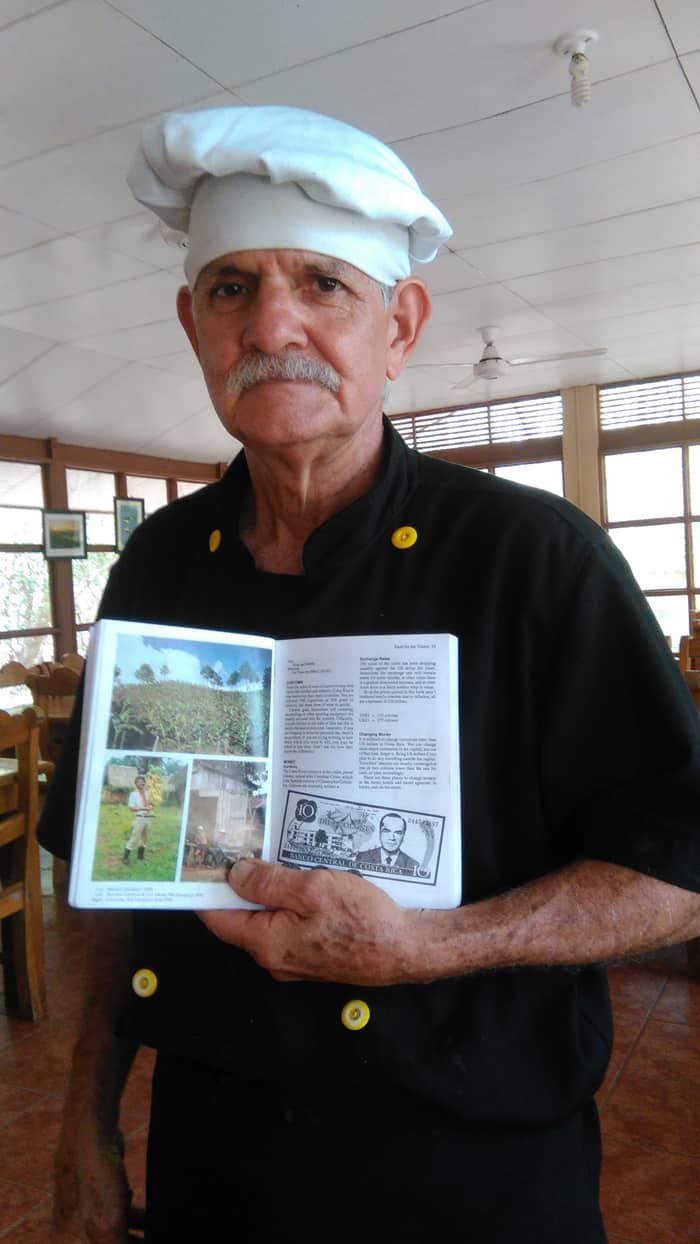

Gustavo showed my around the OTS facility, which features an office, dormitories and a kitchen/mess hall. I immediately found a friend in the chef, Romelio Campos Jiménez of Sarapiquí. I was fortunate that my visit would end a day before a group of 70 students arrived, so I was able to spend time with don Romelio, Gustavo and other employees as we all shared a table for lunch.

As both a compliment and a warning, the food is excellent, and in the form of a buffet with no limits to the number of trips you can take. Gustavo and I both lamented this fact a few times during my stay as we patted our overfull bellies. There is also a large cooler that dispenses cold water — not as filling but very necessary in the heat.

Prior to my tour I walked over to the observation pier that extends out into the wetlands and was confused by what I saw. Why was a small herd of cattle roaming freely in the wetlands among the whistling ducks? I would learn more about that later. I also discovered that I should have brought something other than a telephoto lens, as much of the wildlife followed the style of the iguanas and were loath to move away.

Since I’m not a biologist, or any other kind of scientist, my conversations with Gustavo during our tour were limited to keen insights like, “It’s strange that the iguanas don’t seem scared of people.”

Gustavo smiled and dead-panned, “That’s because we don’t eat them here.”

This is true, but I also later learned that, for tracking purposes, researchers have tagged a number of the iguanas with beads that are pierced into their backs. I suppose that an involuntary piercing is better than being eaten, but, personally, I’d still run.

We used my car for the free tour, which was good, as there was a lot of ground to cover. It was even better when the guide turned to me and asked if my car had four-wheel-drive and, if so, if I’d like to drive out onto the muddy path recently cleared by heavy equipment.

One does not say no to this kind of opportunity. I don’t suggest trying this in a rental car, or without permission and accompaniment of a guide. If you do use a rental car, you’re going to need to plan ahead as to where you can find a lavacar (car wash) and practice your best vacant stare so you’re prepared when the rental car agent asks you why there’s mud and grass glued to the bottom.

We slid down the muddy trail cut through a huge field of cattails and eventually stopped about 100 meters shy of a small lake tucked away between some limestone hills. The shallow lake, which is called Laguna Bocana, is home to a population of crocodiles that abandon it when it dries up in favor of caves in those nearby hills (another reason to avoid spelunking). One of the resident researchers has been studying these crocodiles for nearly four years. Unfortunately, last week’s unexpected early end to the dry season compelled the crocs to return to the once again water-filled lake, so the cave study will have to wait.

Over the next couple of days I was able to take in the various trails on my own and saw far more wildlife than I’d expected. Several of the trails go up into the hills, and it is well worth the modest effort of the hikes to take in the differences in the forest and, of course, the view.

My final morning I shared a guided boat tour of the Tempisque River. My companion, a different Gustavo — from Spain — is an avid birder who has traveled all over the world in search of different species. He and the captain/guide had detailed conversations about the various birds we encountered. Much of these discussions were lost on me, but when we stepped back onto the dock Gustavo confirmed that it had been one of his better outings.

All the OTS staff, the independent researchers and the boat captain insisted that however much I had enjoyed the fauna and flora at the park in the dry season, it was nowhere near the quality of the wildlife I would find in the wet season (June through November). I agreed to come back and will likely bring my whole family, though I will have to search our youngest son’s pockets at the end for any iguanas he has attempted to adopt.

I also learned that these delicate ecosystems within Palo Verde face a number of significant challenges from the past and present activities of their human neighbors. The cows, for example, are allowed to roam alongside the ducks as part of an effort to free the wetlands from the tenacious grasp of typha (cattails). In addition to the cows, park staff uses heavy equipment to try to uproot and kill the typha. The work is never done, as each long, brown tail of a typha plant contains roughly 250,000 seeds. These efforts have gone on for a number of years and are not without controversy.

The crocodile population in the river is also at risk. The percentage of male vs. female crocs, which should be roughly 50/50, is severely tilted towards the males. Researchers are studying potential causes for this problem. Is it global-warming-induced temperature variations for the crocodile eggs within the nests? Is it instead discharges from the tilapia farms up-river which use chemicals to promote sex changes in the fish, as male tilapia are larger and male-only populations are more profitable? Whether or not this practice and how it is being administered locally has any impact on the crocs or the river is something experts will have to decide.

The only sad element of our otherwise fantastic river tour was the never-ending line of dead fish floating among the leaves and branches — fish which are eaten by the birds and crocs. Here again there is no easy answer. The captain/guide feels it is linked to chemical runoff at up-river farming operations.

Ignoring these challenges won’t make them disappear. Visiting Palo Verde and spending money to support it and the research being conducted here can help, as will any subsequent efforts to tout its beauty and wonder to others. I will soon return to continue doing my part to help, and I encourage anyone interested in seeing and preserving this special place to do the same.